We Live in a Police State: Some Thoughts On the Manhunt in Boston

I’m going to start this post by saying that I have nothing interesting at all to say about the manhunt and subsequent capture Dzhokhar Tsarnaev — like most people, I was glued to my television. Like most people, I felt like I was watching a particularly good action movie. Today, I have this weird sense of time reversed, as if the Boston bombings were just a preview of what might have happened had the police not caught the subjects. The sad thing is that the bombings were a real event — but cable news has so effectively turned tragedies into entertainment that it’s impossible to separate what’s real from what’s been manufactured unless you are actual participant.

On the way home from a friend’s house, where Caleb and I watched the final hours of the chase, we turned on NPR. The segment airing at the moment, only a few minutes after Obama’s speech, was about the way the media covered the event. There was a lot of talk about how much time should have been devoted to the coverage in comparison to other news — and whether or not its irresponsible to heighten people’s emotions by reporting events as they unfold in real time, without first verifying all of the facts.

One thing that I’ve noticed a lot lately, and not just in connection to the bombings, is how much the media writes about itself. I would say that 20% of the coverage I saw in The New York Times, the New Yorker, NPR and other intellectual media outlets was about how the event was being reported. Here’s the thing. It doesn’t fucking matter. Maybe a good article could be written in the weeks after the event about the meaning of it all. But the truth is that people were enraptured by the event — if NPR or any of these other fucking outlets had stopped reporting on it, the general public would have just changed the station. It’s what people wanted to hear about, not because they were being manipulated by big businesses, but rather, because it was a fucking excellent story.

Not to mention that by reporting on the reporting, NPR was doing exactly what it was concerned about — not reporting things that actually mattered, like the fires in Texas, or, I don’t know, gun control, or the war in Syria. Or fucking Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. Listening to them talking about wasting time, while wasting time, I wanted to walk into the studio, stand in front of the host, tilt my head, and say, “Are you fucking serious?”

I’ve recently come to the realization that talking about how bad the effect of something is is equally as insipid as the thing itself. For instance, there was a lot of chatter about how Twitter wasn’t an accurate news source, and how CNN was misreporting the unfolding events. On the surface, it’s easy to get outraged — of course facts are important! But when you think of what media is these days, I think the best analogy is sportscasting. People on Twitter aren’t reporting information — they’re commenting in an attempt to find meaning in something unfolding before their eyes. Just as a sportscaster might say, “looks like that was a foul on the 50 yard line,” someone on Twitter says, “there might be a chance that Tamerlan Tsarnaev was doing something suspicious in Russia for six months!” Then, everyone waits for the referees — or, say, The New York Times, to make the final call.

Ultimately, however, none of it matters. All of that chatter that went on for the past week — and will continue to go on — is ultimately just a cosmetic and collective way of bonding together as a society. The facts now come from officials, almost as the sort of summary sentence at the end of a long, rambling theoretical essay.

The difference between now and fifty years ago is that we have constant image-based evidence upon which we can formulate our own theories. Hear me out. Fifty years ago, when there wasn’t a camera charting literally every single moment of our lives, chances are that in any given tragedy, there would be two or three images from the crime scene. The media would be relied upon, therefore, to explain what had happened in words, so that people could understand in their mind’s eyes.

Now, with the proliferation and speed in which photographs are transmitted, we can usually see for ourselves what the media used to describe. So the media’s role has changed — now, they are tasked with providing us, in our own homes, with access to the conversations that are going on in the larger world. Much in the same way that a town, after a tragedy, would gather together in the central square — now, the media is that place where we can all share our theories, our concerns, our sorrows, our need for human connections.

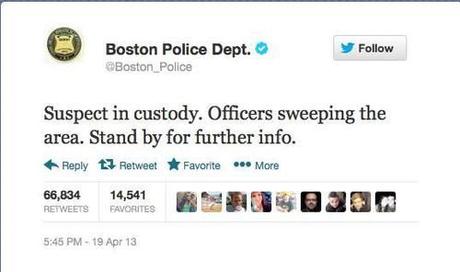

Guess where the facts come from? The government and the police. And where do they relay those facts? If you were watching the news last night, you know that they now come from a sort of insane place. And that place is Twitter.

While the cable news was burbling and bustling about, and the newspapers were fifteen minutes behind, the Boston police released a tweet that they had the subject in custody, and that he was still alive. We all got the news in the same moment. Because officials, rather than having to use the media, now can speak to us directly.

Which, when you think about it, is sort of a scary thing. I don’t know if anyone felt like this, but the most shocking thing about watching this whole thing unfold in the past week was the realization that we live in a heavily armed police state. Nothing is anonymous anymore. No one is untraceable. There is no where you can walk, no where you can hide, no where that you can speak without there being some record of your existence. A camera even caught Dzhokhar as he was climbing into the boat where he hid.

It took almost no time for the police to figure out who the bombers were, thanks to images, and it took them almost no time to respond. The pace at which not only the BPD, but also the ATF, the FBI, the National Guard, the CIA, and a number of other government enforcement agencies mobilized was astounding. The streets were filled with men bearing machine guns, and black tanks trained for counter-terrorism efforts. Within a matter of hours, they were able to shut down an entire city.

When Dzhokhar was caught, the government revealed itself even further. The police were equipped with all sorts of scary things — nerve agents, light bombs, protective shields. They could have taken him anyway they wanted — they were fucking loaded with tricks.

All of this was awesome in the case of the Boston bombers, who seem like they are probably guilty, but terrible for innocent people who may one day commit no crime, but be targeted for reasons that, given that our government has so much power, remain opaque to us.

Which is where my plea to the media comes in. Don’t talk about how you report events in the moment they’re happening. Don’t talk about how little money you make. Don’t talk about how hard it is for your fucking industry to survive. Don’t talk about how much you pay freelancers. Don’t fucking talk about your fucking goddamn process. Talk about how you uncover and temper government practices. Invest in long term investigative stories that uncover things that we, with our eyes, can’t understand from photographs. Give things a historical context. Help us understand what it means to live in the world we live in, and how we can prevent our heavily patrolled police state from taking away our rights. How we can continue to demand that our powerful government acts in our best interest.

But first, maybe tell me if Dzhokhar was shot during the stand off with his brother, or if he was hurt during the shoot out in the boat? I don’t have the time to cull through Twitter for the information.