The view from Bobonong, she mused: was that how the world looked to Mma Makutsi? It seemed an odd thing to say, and yet all of us had a view from somewhere, a view of the world from the perspective of who we were, of what had happened to us, of how we thought about things (Alexander McCall Smith, The Minor Adjustment Beauty Salon [NY: Random House, 2013], p. 40).

If every journey we undertake has the potential to be a spiritual one (see my previous posting), then every book we read has the same potential, since reading a book is going on a journey. Isn't it? On our recent trip, I read the latest in Alexander McCall Smith's Precious Ramotswe series, and Mma Ramotswe's musings about Mma Makutsi's unique view from Bobonong leapt out at me as I read.

And then this happened: on one of the mornings when we were in Dyersville, Steve wanted to drive to the Catholic cemetery and take photos of family tombstones in the morning light. I decided to use his tombstone time as exercise time for me.

Since the cemetery is large (and well-maintained, in venerable Germanic fashion) and peaceful and park-like, I walked like a fiend up and down neatly ordered rows of Schindlers, Christophs, Kortenkamps, Klostermanns, Boeckenstedts, etc., thinking how fascinating it was that Steve and I have seen the very same clusters of the very same names when we visited the villages in the Bavarian Oberpfalz from which his Schindler and Christoph ancestors came to Dyersville, and the Oldenburger villages near Hanover from which his Rolfes relatives came to the same part of Iowa.

I walked among the dead thinking, Yes, my view as a Catholic theologian has definitely been the view from Bobonong. It's the view from somewhere —from who I am, from what has happened to Steve and me, all of which radically affects how we think about things. It's a view for which there is absolutely no place in the church today: and therein lies the rub of writing about it, of writing about our spiritual journey.

How do you tell a story about a spiritual journey that no one else is likely to recognize as the story of a spiritual journey at all? Since there's no place for such a journey within the community of faith about which you're writing, to which you're addressing your narrative . . . .

Schindler, Christoph, Kortenkamp, Klostermann, Boeckenstedt: one time more past the tombstone on which sits a little white marble angel, a child-angel into whose upraised hands someone has put a yellow glass star — where do we fit, Steve and I, among any of these neatly arranged, lovingly maintained Catholic rows? I walk, and I think quite specifically of a theologian whose work I've admired, a man whom I've met, who used to be a Jesuit priest and who is now married (to a woman), who has been critical of what I've written about the place of the scriptures in Catholic theological assessments of homosexuality.

He thinks that I don't recognize the force of biblical taboos against homosexuality, as I call for inclusion of gay folks in the church. This is a man who says he's in favor of full inclusion and acceptance of gay people in the Catholic church.

But he's a married heterosexual man who has had all the advantages of a (free) Jesuit education, who enjoys every astonishing advantage of straight married men in a world designed to give astonishing advantage to straight married (white) men, and he thinks the bible is somehow his and not mine. That it's written to afford him advantage and to disadvantage me in a very radical and fundamental way.

It's written to stigmatize folks like me. And so I should begin my analysis of the scriptures as a gay Catholic theologian by recognizing that the bible is a problem for me, and not my bible at all. It stands against me and is not for me, as it is for him.

This is a man who enjoys tremendous entrée in Catholic theological circles. He could have done something to assist Steve and me. To show solidarity with us when the Catholic theological academy turned its back on us.

He did nothing at all.

Schindler, Christoph, Kortenkamp, Klostermann, Boeckenstedt: I walk and I think about all of this. How do you tell your story from Bobonong in a world so radically skewed to turn you, from the very outset, into a non-person? In a world determined to deny you the right of speech even before you've opened your mouth? What's the point of trying to tell your story when only the story of powerful others who exclusively control the sacred texts counts in the long run?

As I walk, I think of Mary Daly, of her statement, If God is male, then male is God. I think that in a different age, a more believing one, one more configured according to faith and religious institutions, this statement would be nailed to the doors of every church in the world. It would have precipitated a new Reformation.

Since no God who exists at the behest of one segment of the human community and to the marginalization of another segment of the human community (of half of the human community!) is worth worshiping. The very notion of God has become a stumbling block from the moment we define God as as a man — and thereby deify men. Quite specifically heterosexual men . . . .

I count the tombstones one more time, thinking how pleasant it would be to lift that yellow star from the angel's hands, to weigh its heft in my own fingers (a temptation I resist, since it's there at the loving behest of someone, of someone who loves the child buried in that grave, and who am I to disturb anyone else's loving arrangements?): and I keep mulling over Mary Daly's story with its (entirely failed, as far as I can see) reformational implications for my church and many other religious communities at this point in history.

I remember how one of the first times I ever heard her name was when a Dominican priest-theologian I know, a gay man, told me as he laughed uproariously that Daly was a clone of a typical lesbian nun, a man-hater who should never have gotten tenure at Boston College.

This was a man who had enjoyed every advantage of maleness within an institution shaped in every way possible to afford him advantages simply because he was born a man, while it disadvantaged Mary Daly in every way conceivable because she had the misfortune to be born a woman. This was a man who, as a religious man, a member of a religious community, had enjoyed the wonderful (free) education afforded him as a Dominican novice and priest.

He's a theologian who has never had any difficulty finding a job, since his institution owns the universities in which he has worked, going from grace and glory in one job to grace and glory to another job. He's a man who could have reached out to Steve and me when the Catholic theological academy turned its back on us.

In face, he did nothing at all to assist us, except to pretend he hadn't even seen us at the last meeting of the Catholic Theological Society of America we ever attended, as we walked past him in the aisles of the book display room.

He is a man who feels no commonality whatsoever with Mary Daly — as I myself instinctively do — whose male gayness does not in any way intersect with her lesbian feminism. He is a man not entirely different (in my head, at least) from another gay theologian who is a former Dominican who also enjoyed the advantages of a wonderful (free) education before he crashed against the rocks of the institution's savage homophobia and found himself booted from his community.

A former priest and gay theologian whose work I do my best to appreciate, but which ultimately cannot speak to me insofar as it comprises and enfolds at its foundational levels his clerical experience, with its remarkable unacknowledged advantages of which Steve and I, as lay theologians who paid for our own educations and have had none of the support of clerical networks afforded to gay priest-theologians when they run afoul of the institution . . . . Support and entrée of which Steve and I can only dream . . . .

I walk among the tombstones, with the dead, and I wonder: what place for the two of us? And how to tell a story that isn't even recognized by our community of faith as a story at all? Is it worth even trying to tell this painful, going-nowhere story? When life is so short and the years left to us may be so few?

I wonder.

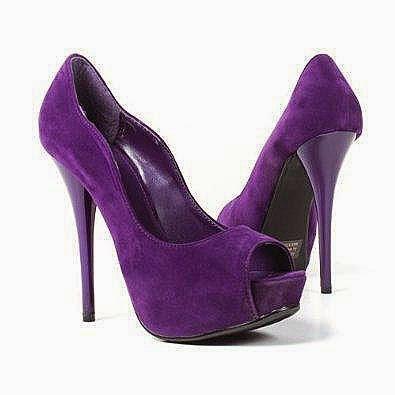

The photograph of Mma Grace Makutsi's purple pumps is from Charles Marlin's review of The Minor Adjustment Beauty Salon at the Clarion Friends blog.