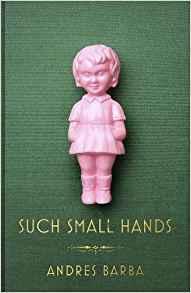

Such Small Hands, by Andrés Barba and translated by Lisa Dillman

It’s hard to talk about Such Small Hands without using words like dark, sinister, troubling. It’s a one-sitting read which lingers long in the memory, much as you might wish it didn’t. It’s very, very good.

Possibly the creepiest cover of any book I’ve read this year. Here’s how it opens:

Her father died instantly. Her mother in the hospital.

“Your father died instantly, your mother is in a coma” were the exact words, the first ones Marina heard. You could touch those words, rest your hand on each sinuous curve: expectant, incomprehensible words.

Marina is a young girl suddenly orphaned. The accident leaves her numb and alone. Her only friend is a doll the hospital psychologist gives her to help her with her recovery.

The early chapters are all from Marina’s perspective. Overnight her world has become a strange place of clinically concerned adult figures and anonymous hospital spaces. From there she is sent to an orphanage, a thing she can’t even imagine before arriving:

It was too hard to look forward to the orphanage; she didn’t know how to do it. And unable to picture it, random images jumbled together and came gurgling out like a death rattle. She looked at dolly to quiet them. Someone had gone to her house and packed her a doubtful suitcase. Winter clothes and summer clothes all jumbled together.

I love that phrase ‘a doubtful suitcase.’

With Marina’s move to the orphanage the narrative changes and alternates between chapters from Marina’s perspective and chapters from the perspective of one (or possibly several) of the orphanage girls. One or several because the orphanage girls don’t distinguish – they have spent their short lives growing up together and the experience of one of them is still the experience of all of them.

When class was over we liked to play. We’d sign as the jump rope hit the sand with a dull crack. To get in the circle you had to pay attention, had to calculate the jump rope’s arc, its speed, adapt your rhythm to the chorus.

Marina’s traumatic experience leaves her quite unable to adapt her rhythm to the chorus. She is silent and watchful. She doesn’t join in. In the communal showers they notice she has a huge scar from the accident. None of them have anything like that. Marina is different, and by being different she makes the girls aware that each of them is different too. Marina is their apple of knowledge.

We became aware of each other and we felt naked before that body that wasn’t like our bodies. For the first time we felt fat, or ugly; we realized that we had bodies and that those bodies could not be changed. Just as she had materialized, we materialized: these hands, these legs. Now we know that we were inescapably the way we were. It was a discovery you could do nothing with, a discovery that served no purpose. We huddled together when she approached. We were afraid to touch her.

It’s fair to say that the book is already pretty dark by this point, but it gets much darker. Marina’s difference holds a power over the other girls and they revenge themselves on her for it with a campaign of bullying and spite. She is their victim, but at the same time she holds a glamour over them, a fascination.

They’re children. They want to love her. They want her to be one of them. They have no idea how to process the emotions she’s given rise to: fear and desire each unfettered by language because they’re yet to learn the words to bind them with.

Part of what’s so marvelous about Such Small Hands is how well it captures the intensity and magic of childhood. Usually when we talk about magic in that way we mean it as a good thing. Unicorns and rainbows and fairy godmothers. But childhood magic isn’t just lazy summers that seem to last for ever. It’s monsters under the bed, reclusive neighbours rumoured to be serial killers, avoiding stepping on cracks for fear that if you do you’ll break your mother’s back.

Everything here has a logic, but it’s the logic of small children. At times it’s innocent and instinctively affectionate. At other times it’s capricious and cruel. We have to learn how to manage our feelings. We have to learn to be civilised. Barba conjures a dark fable from apparently ordinary ingredients and the result is one of the most shocking and exciting novels I’ve read this year.

Other reviews

Several, including doubtless many I’ve forgotten to keep details of. Trevor of themookseandthegripes loved it here. Tony of Tony’s Reading List was similarly blown away here. And far from lastly, David of David’s Book World was equally impressed here and through his review convinced me to give it a try. Edit: I missed two that I had bookmarked: from Stu at Winston’sDad’sBlog here and from Eric at Lonesome Reader here.

There’s also an interview with translator Lisa Dillman here which is worth taking a look at.

Filed under: Barba, Andres, Novellas, Spanish Tagged: Andres Barba