Could it be him?

The Walter Murch I was thinking of had gone to Johns Hopkins a couple of years before I had and, like me, has associated himself with Professor Richard Macksey. When this Walter Murch left Hopkins he went West and ended up in the film business, where he’d worked on a number of important films, including Apocalypse Now, which which he won an Academy Award (aka an Oscar) for sound.

Was this that Walter Murch? Yes, it was, and he liked what I was saying about Apocalypse Now. Since then we’ve carried on a casual and sporadic email correspondence.

Most recently we’ve been talking about the collective nature of movie making. By convention overall creative responsibility for a film is credited to the director, and for sufficient reason. The problem is, however, that our basic cultural model of creativity is one of individual creativity, and that does not do justice to any number of activities, from scientific laboratories, through basketball teams and ballet companies, the founding team of a high-tech start-up and, yes, a motion-picture production ensemble.

Walter sent me a passage from a 1994 journal entry:

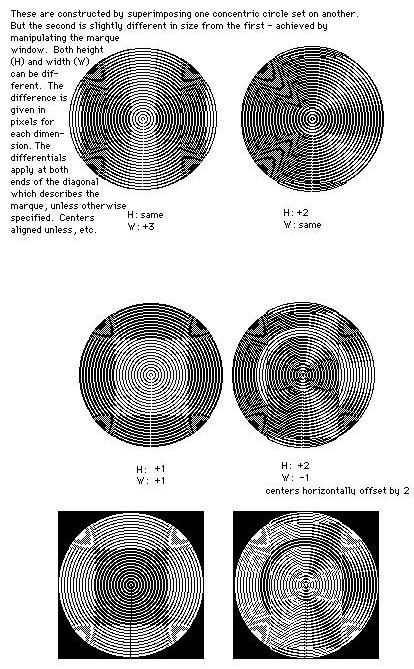

Reading Penrose - the fact that billiards, which is the game usually given as an example of mechanical physics in deterministic practice, is not immune to vanishingly small initial conditions for the outcome of complex sequences • A line of 20 balls may be arranged in a zigzag such that each will hit the next in sequence when tapped by the cue ball. But exactly where the last ball will wind up after it is hit is subject to something as small as an intake of breath in the neighboring town. If there are 26 balls, a molecular disturbance in some neighboring galaxy will influence the outcome • Reminds me of my 'magic light' hypothesis of film: that film is the sensitive receptacle of everything that happens during the filming - what the assistant electrician had for breakfast, etc. - caught somehow, invisibly, in the amber of celluloid. In the future, people will be able to see this complex of interactions directly by shining a special ‘light’ through the film. It will look like some 5-dimensional moiré pattern, endlessly shifting, endlessly fascinating.By Penrose I assume he meant Roger Penrose, a mathematician who had published a number of general interest books in the 1990s. You can find images of moiré patterns all over the place on the internet, or you can look below for some simple examples I ran up on my “classic” Mac back in 1985 or 86:

Walter then went on to comment on his old journal entry:

What I meant by "Magic Light" is the discovery of some new force (Force 5) of nature, which has been with us all along but of which we are presently as ignorant as Newton was of electromagnetism. Using this new “force” as a beam, these hypothetical people of the future will transect our films and see - not the images which we see - but some fascinating interaction of all the people who worked on the film, in all its unexpected contingency, and this will be much more satisfying (to them) than the film itself. And it will be a wonder, to those future people, that we could accomplish this filmmaking without any knowledge of “Force 5”, which will be as crucial to them in their society as electromagnetism is to us today. As wondrous as is the construction of Gothic cathedrals to us today: we can hardly believe that our ancestors achieved these miracles with only human and (literal) horse power, and with no engineering textbooks.And you could add: Duke Ellington and Shakespeare and the Egyptian Pyramids and many other things to this list.

Combining these two passages we get a sense of a film as a very compact “distillation“ of the diverse events surrounding and accompanying it. One might hazard the word “essence” but I fear it has too much of the wrong baggage associated with it. I’m a bit reminded of the JPEG compression for still images and the MPEG compression for video images. You “squeeze out” the redundancy and get a much more compact encapsulation of the information. The, at playback, the redundancy is added back in and you see the full photograph, or video image.

Walter goes on:

I think part of the mystery is that occasionally there is a balance of forces - what Koestler called the autonomy of the part and the wisdom of the whole - where the “part” (whatever it is) makes autonomous decisions that would be impossible for the theoretically guiding force (whatever that may be) to make. And that these decisions miraculously further the higher goal of the “organism” (Duke Ellington's sound, for instance: Duke did not have to tell each of his musicians exactly what to do at every moment) Similarly, if everything that is done on a film had to be expressed in “machine code” (e.g. “turn thirty degrees to the left and cock your right eyebrow”) the film would never get off the ground. People talk about this happening in sports, in battle, in every communal undertaking in fact. It is the human equivalent of the miraculous (to us) ability of fishes and birds to swim/fly in formation and all turn, repeatedly, at exactly the same moment, as if the school/flock were a single organism.Some time ago I read an interview with Jack Welch, then CEO of General Electric, who talked about he and his colleagues in the executive suite could communicate in “code.” Through years of working together they could speak volumes in very terse ways because their shared experience gave them, well, a code that was meaningful among them but not necessarily to anyone else.

Yes, there are lone creative “geniuses” but I suspect there are fewer of those than we imagine. Creativity needs community and communities breed creativity, or can do so under the right circumstances. We have only just begun to understand such matters.