Russia is massing troops on Ukraine's border, and many believe they are preparing to invade that country. Here is part of Alexander Vindman's take on the situation. Vindman is the former director for European and Russian affairs at the National Security Council.

To date, U.S. foreign policy toward Ukraine has failed to keep the Kremlin in check. When it comes to Russia’s neighbors, Washington has settled for a passive role and has been, at best, fickle in its friendship with Ukraine.

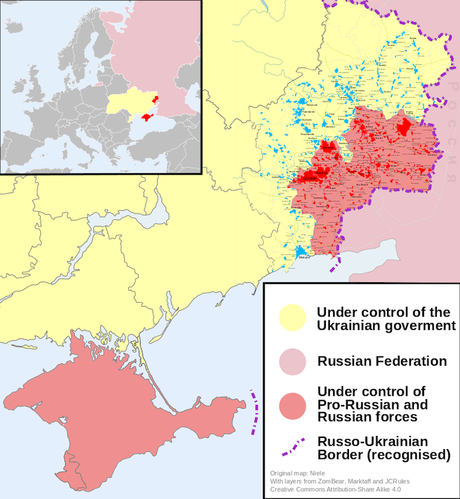

Russia, on the other hand, has been committed to retaining and regaining a sphere of influence over its most important imperial holdings, Ukraine and Belarus. Mr. Putin — no doubt picking up on the decreased American appetite for foreign entanglements over the last few years — has seized his chances with encroachments on Ukrainian sovereignty including the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of the Donbas region. Even interference in Western elections is just another tactic to weaken the West and create a privileged sphere of Russian influence.

Today’s looming crisis in Ukraine is simply the continuation of Mr. Putin’s ambitions. Statements like the one by Mr. Biden on Wednesday — that U.S. interests end at NATO’s borders — have only emboldened Mr. Putin to ignore international norms.

This American neglect must end. After all, the United States and Ukraine share both ideology and long-term geopolitical interests.

Over the past 30 years, Ukraine has made major strides in its experiment with democracy. Despite worrying instances of government-backed corruption — undeniably, there is still more work to be done — Ukraine has made hard-fought progress on reform in the midst of war. Six presidents, two revolutions and many violent protests later, the people of Ukraine have sent a clear message that reflects the most fundamental of American values: They will fight for basic rights, and against authoritarian repression.

A prosperous Ukraine buttressed by American support makes an authoritarian Russia unviable in the long term. Ukraine’s success would upend Russia’s irredentist aspirations for empire and highlight the Kremlin’s failures, just as West Germany’s achievements once did in comparison to the totalitarian East German state during the Cold War. It may even convince the Russian people — who share a culture, history and religion with Ukrainians — to eventually demand their own framework for democratic transition.

To be sure, this doesn’t happen overnight. A generational investment is necessary to realize such a vision. Nevertheless, the outlines of the stark contrast between a prosperous democratic Ukraine and a repressive and economically stagnant Russia are already evident. This is, in large part, why Mr. Putin needs Ukraine to be a failed state.

U.S. support for Ukraine could also help drive a wedge between China and Russia. Preventing Mr. Putin from invading Ukraine demonstrates the strength of the West’s commitment to opposing autocracy and makes Russia a less potent partner to China in their mutual efforts to undermine the Western rules-based international order.

To that end, the United States should consider an out-of-cycle, division-level military deployment to Eastern Europe to reassure allies and bolster the defenses of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This kind of deployment would signal that Russia’s aggression will result in the sort of NATO security posture Russia most wishes to avoid.

And the United States cannot adequately support Ukraine without significant European involvement. The Kremlin wishes to make NATO membership for Ukraine a central issue of any discussions. That’s a distraction right now because an assurance that Ukraine won’t be a part of NATO is unlikely on its own to stop Russia from still trying to bring Ukraine to heel.

The more important issue to consider is that negotiations with Russia should be dealt with at the level of European security. These talks should devise off ramps that alleviate both European and Russian security concerns: for Russia, NATO encroachment and ballistic missile defense, and for NATO, Russia’s over-militarized western border.

The Biden-Putin call on Tuesday opened the door to exactly this kind of discussion. The question that remains is whether Russia is prepared to walk through that door and reconsider its position on conventional arms control agreements such as the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty.

The United States should also engage Ukraine in more long-term bilateral initiatives on security, reform and economic cooperation. This year, Washington has delivered approximately $450 million in security assistance to Ukraine. While this is important, economic cooperation should go further to include backing American commercial investment through the Development Finance Corporation. Washington should also consider maintaining a more sustained high-level relationship with Ukraine that isn’t defined by whether Kyiv is in crisis or not.

There are irrefutable benefits to the existence of a strong, democratic and independent Ukraine as a powerhouse at the crossroads of Russia, Central Asia, the Middle East and Southern Europe. For that to happen, the United States has to be more assertive in the region. Our traditional halfhearted approach has already proven to be a dead end.