“Plan It by the Planets”

Magdalena poster art (movimento.com)

One weekend in April 2011, I happened by chance to be listening to Heitor Villa-Lobos’ beautiful Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5 for soprano soloist and eight cellos. Out of the blue, I remembered that the Brazilian team of Claudio Botelho and Charles Möeller had done a production of the Villa-Lobos, Bob Wright and Chet Forrest “musical adventure” in two acts, Magdalena, about a decade ago in the northern city of Manaus.

The wheels inside my brain began to turn. “That’s as fine a work as any to bring back to the Great White Way,” I wondered to myself. After all, the show originally premiered in Los Angeles in 1948, and then, a few months later, the production came to New York, to the famed Ziegfeld Theatre. The plot is a trifle ridiculous, I admit, sort of a South American offshoot of what passed for operetta at the time; but the music is truly memorable and composed by one of Brazil’s most prolific and talented artists, the incomparable “Villa.”

I brazenly considered the possibility: “Would Claudio and Charles be interested in bringing the work to the Big Apple?” This was one of those nutty schemes I’ve been wont to invent mostly to keep me out of trouble, what for most people would appear to be an impossible dream.

My own experience, however, has taught me that impossible dreams have a way of becoming reality. “I’d love to have Claudio’s thoughts on the matter,” I decided, as the gorgeous voice of the late Anna Moffo filled the room with Bachianas’ melody.

I dashed off an e-mail to Claudio in the hope that he would respond to this latest effort at revitalizing the once vilified Magdalena. Just last month I posted an article about the making of this long-forgotten work (see the link: http://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2013/11/07/lo-the-savior-approaches-part-five-villa-lobos-magdalena-broadway-bound/), the result of several years’ worth of research on my part to understand the reasons behind the failure of Villa-Lobos’ lone Broadway excursion.

The principal problem at the time, among many, lay in a crippling musicians’ strike that not only made matters worse at the box office, but prevented the musical from being recorded and preserved for posterity. Another issue was the composer’s health and his unexpected bout with cancer.

The past is past, and we can surely learn from the experience. But as far as the present goes, what is it that’s prevented this “musical adventure” from flourishing on its own terms? There’s only one way to find out, and that’s by asking. And who better to ask than one of the acknowledged Kings of Brazilian Musical Theater?

“Now you really got me excited!” Claudio shot back in response. “I ADORE Magdalena! It’s a dumb story, completely unrealistic and dated and (but for this very reason) very stimulating nowadays, especially because [the show] deals with dictators and the power of such people as Hugo Chavez and other tyrants…”

Finally, a ray of hope! I forged ahead with my mission.

“We did a concert version in Manaus, for the annual Opera Festival there,” he went on, “not at the Teatro Amazonas but in a club, with singers, a full orchestra, a chorus of children and native Indians, a ballet, the works. It’s such marvelous music!”

Scene from Magdalena revival in France (ruedetheatre.eu)

“I agree with you 100 percent!” I responded, with equal enthusiasm. “Villa-Lobos is long overdue for a major revival in this country. He was a big favorite of American audiences in the 1940s and ‘50s — everybody knows his Prelúdios and Estudos for guitar, such incredible stuff. And who isn’t familiar with the Bachianas or The Little Train of the Caipira?”

I asked Claudio if he had the original English text in his possession. He didn’t, but he did send me his Portuguese adaptation, which he used in Manaus in 2003 and which formed the basis for new productions in Rio, at the Teatro Municipal in 2011, and São Paulo in 2012.

“That’s pure Broadway,” Claudio noted, “especially if we try to take away a bit of the ‘operatic’ voices from the 1940s and do it with a younger (and braver) cast. I adapted the book for Brazil, more for the Brazilian style of humor, but I must confess: the script as written makes for a delightful parody.”

He continued extolling the virtues of this neglected masterpiece with an eye towards its musicological context: “In truth, Magdalena is a mix of many works by Villa. There are themes taken from the Bachianas and from his choros, bits and pieces of songs, even those children’s numbers he set to music [i.e., Cirandas, Impressões Seresteiras] and the like.”

A major stroke of luck was Claudio’s close relationship to MTI, or Music Theatre International, the agency that licenses musicals for production to schools and theaters around the globe. He helped me get in touch with Richard Salfas, Vice President for International Licensing, who kindly sent over the book for my perusal. In addition, both Claudio and I had, unbeknown to one another, ordered the same Sony CD of the work. That’s double the trouble, but twice the fun!

“Food for Thought”

I thoroughly enjoyed listening to Magdalena, but I could tell that the work needed some indulgence on my part in order to, uh, “swallow” the convoluted story line. I won’t bore readers with its untold absurdities, only to mention that the Latin American dictator of the piece, one General Carabaña, faces a hefty “mouthful” of obstacles at the end, which leads to his farcical demise by over-eating.

General Carabana in Paris (musicalavenue.fr)

I received the complete text within days of the request. After devouring its contents, I concluded that Magdalena, as the book was conceived by Frederick Hazlitt Brennan and Homer Curran (credited as the show’s producer), is rather silly, somewhat outdated, and even condescending toward the native-Indian population (in this case, the Colombian Indians).

Here’s what I told Claudio: “The sensibilities of people from the 1940s and ‘50s were very different from our own ‘politically correct’ era, and I can understand and appreciate those differences. Besides, if the music is superior to the text — and I am absolutely convinced it is — one can try to overcome some of the racial and ethnic stereotypes that are prevalent throughout the story.”

Claudio’s reaction was, as always for such a consummate professional, a most thoughtful analysis of the problems associated with the work. “I think the book of Magdalena shouldn’t be taken as a serious piece,” he acknowledged, “but as more of a pastiche. It was written to be taken seriously, and all that operatic delivery of the music tends (in my opinion) to make it sound [overly] dramatic, when it should be melodramatic and funny instead. If we [ever] get to put our hands on the script, we should treat it from the point of view of ‘Monty Python in the Amazon,’ but nothing like Fitzcarraldo, if you know what I mean.”

Ah, yes, Monty Python! I love it already: “Always look on the bright side of life,” right? How can you lose with a combination like that?

My streams of consciousness were hammered out in no time flat: “That’s exactly what is needed with Magdalena: more humor! I have an idea already: in the first scene, where the romantic lead, Pedro, sings the number, ‘My Bus and I,’ there is a group of passengers who leave the bus and comically ‘pray’ for their deliverance. And in the next scene, in Paris, there are male and female guests at the Little Black Mouse Café.

“My idea involves having one of the ‘passengers’ (or ‘guests’) appear as Villa-Lobos. He can show up throughout the musical, in various guises, as a ‘tourist’ or perhaps as a ‘resident’ of Paris. It’s well known that, in 1912 (the time period of the story), Villa had visited many parts of Brazil — including, it is speculated, parts of the Amazon region, although this has never been substantiated. In addition, between the years 1922-23, and again, in 1927-30, Villa lived and worked in Paris, which he continued to return to for years thereafter. So he was a familiar sight along the café circuit!

“It would be a fun way to have this character continue to appear as a sort of extra — a recurring personality who shows up on occasion and either comments on the action or participates as an onlooker. At the end, Pedro, Padre José or Maria can attempt to ask this fellow, ‘Hey, who are you?’ and the character can respond, ‘My name is Heitor Villa-Lobos, but you can call me Villa!’

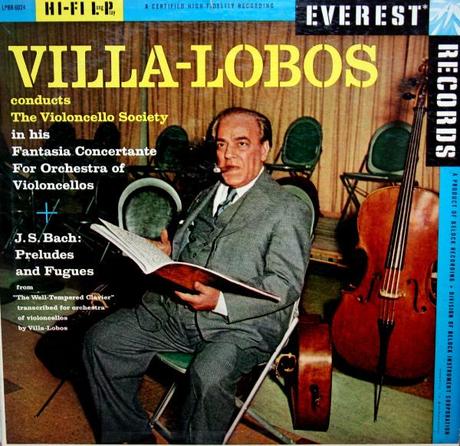

“This is just one idea. Maybe you can invent other scenes that will make this musical lively and topical. Another aspect of Villa is that he insisted on bringing along his cello wherever he went, to play whenever he felt the urge. Our Villa can bring his cello with him to Colombia, as well as wear one of those jungle pith helmets or smoke Cuban cigars. He can also carry a cue-stick (Villa loved playing snooker with his friends). Again, these are just little character traits and quirks that I thought could add color and comedy to the story.”

Heitor Villa-Lobos and his ubiquitous cello

I was obviously putting myself out on a limb. Imagine, me, a complete novice as far as producing and directing were concerned, suggesting to a recognized authority such as Claudio Botelho how to fix a Brazilian musical… I must’ve been delirious!

“I love the idea,” Claudio answered back. “But if you allow me an opinion…” That’s it, I blew it. I had gone too far. Now I was dreading having to read Claudio’s e-mail, with the thought clearly in the back of my mind: “He must think I’m totally out of my mind.” I pressed on, but with much trepidation…

“Let’s put this Villa in, yes, but we’ll make him an ‘impostor,’ a fake Villa, who tries to take advantage of the fact that [the real] Villa-Lobos is starting to become famous in Brazil and elsewhere with his music. When in the end, the real Villa-Lobos appears and shows everyone that the fake Villa has been impersonating him all along. Something like that! What do you think?”

What did I think??? I could only paraphrase in my head what Fernando Lamas (as duly personified by Billy Crystal) was prone to say in the flesh: “That sounds mah-ve-lous! Ab-so-lute-ly mah-ve-lous!”

“And this fake Villa,” Claudio continued, “could have some interaction with the fake astrologer Zoggie, no? Oh, and I’m sure the real and the fake Villa could both bring their cellos together [on stage]. We could have a ‘choros’ number in the show. The very first choro on Broadway! Ha-ha!”

Dueling cellos…hmm… Well, why not? “Yes, yes, that’s it exactly!” was my heartfelt reply. “By George, I think you’ve got it! It will be a Brazilian Comedy of Errors. We’re all on the same page, Claudio. No matter if the play is in English or in Portuguese, it would be as you say, ‘Monty Python Meets the Amazon Jungle,’ as well as a musical adventure. The real Villa confronts the fake one and the two of them have a ‘duel to the death’: one plays the cello, while the other strums a choro on his guitar. In the meantime, the soprano (Maria) sings a seresta or a bachianinha… The possibilities are endless, because it’s all about Villa’s music, isn’t it?”

I was starting to get carried away at this point, but I just couldn’t help myself: “The fake astrologer Zoggie reminds me so much of Geni from Ópera do Malandro, doesn’t he? As you know, many of the astrologers [called videntes] in Brazil are gay, so it would be great to have Zoggie do his séance in the manner of a Brazilian palm-reading. I’ve had this experience in Brazil myself. My wife and I once visited one of those astrologer types, and they were extraordinarily good at ‘predicting’ the future… It’s just another idea to bounce off you and Charles.”

“Magdalena, Come into the Valley!”

I listened attentively once again to the Magdalena CD. And you know what? I liked it even more. The numbers I initially thought were good, were even better the second time around: “My Bus and I” (a very catchy tune); “Food for Thought” (really excellent — it will remind listeners of the Habañera from the opera Carmen); the entire episode in Paris (similar, in some ways, to the Café Momus scene in Puccini’s La Bohème, or La Vie Parisienne by Offenbach); and the beautiful “Magdalena” interspersed with that looney “Broken Pianolita” number.

Luciana Bueno as Teresa (www.youtube.com)

Musically speaking, the second act was not as good as the first — there weren’t as many worthwhile tunes. But I did enjoy “Piece de Résistance,” an absolutely smashing showpiece for coloratura soprano. This number (along with “The Broken Pianolita”) was THE BIG HIT of the evening when it was done by Irra Petina, who also appeared in Forrest and Wright’s previous musical, Song of Norway.

The characterizations of Teresa and General Carabaña I found charming and irresistible — those two individuals work well together. On the debit side, Maria (soprano) and Pedro (tenor), as well as the Padre José character (bass), along with the “Miracle Madonna” finale of Act II, were typical of the period. The song, “Freedom,” was rather weak: compare it to some of the stirring choruses from Les Misérables (for instance, “Do You Hear the People Sing?”).

Still, I couldn’t help but be reminded of The King and I (with the duet, “We Kiss in a Shadow,” serving as the main offender), of the kind of faux exoticism that was the norm back then; and especially Kismet, the show Forrest and Wright cobbled together after Magdalena folded. The English lyrics to Magdalena’s songs were, in my opinion, a bit too old-fashioned and banal for my taste. In contrast, Claudio’s Portuguese versions were better than the originals! I’m happy to report that he did an excellent job in adapting the book. But the problems, as noted above, remain with the original — and that’s a big concern for anyone wanting to undertake this “musical adventure.”

Considering how much Claudio has contributed to Brazilian musical theater over the course of the past 20 years — by turning the genre around and bringing it back from the edge of oblivion — the final word on Magdalena’s fate should rest with him:

“You’re absolutely right, Joe: it is more of an operetta. And unfortunately it’s not on the same level as either The King and I or Flower Drum Song, which would be the same sort of operettas, too, but with more dialog. But let me tell you one thing. Some time ago, a very prominent Brazilian musician of choro came to me with an idea: ‘Why in hell doesn’t somebody think of transforming Magdalena into a ‘real’ Brazilian musical?”

“What did this fellow mean by that?” I inquired.

“He meant: why not re-orchestrate it for a more Brazilian ‘sound,’ with acoustic guitar, percussion, cavaquinho, bandolim, and of course the necessary reeds and strings. But what he meant, too, was: transform the original rhythms and the European sound that Villa put into the original work into a genuine Brazilian piece. In a way, it’s what Forrest and Wright did with Kismet: they picked up the opera Prince Igor by Alexander Borodin and transformed it into a Broadway musical. We would be doing the same thing, but to another degree.

“I never really stopped to think seriously about that subject. But the idea sounded good to me as a pre-project. I did something like that with Chico Buarque’s Ópera do Malandro: the original concept was based on the Brecht-Weill model, i.e., the story stopped at one point and the songs would come in at the end of a scene. So I turned the music more into a book, mixed it with new dialogue, and… well, I think it worked out well (in spite of the Portuguese press accusing me of “fucking around with the revolutionary aspect of the original and turning it into Broadway trash,” hahahaha… I love that!).

“I never thought of putting Magdalena on in the way it currently is, theaters don’t need us for that. Any competent conductor or director can stage it at the Metropolitan Opera or Lincoln Center, and that’s all. People will go and see a sort of archeological treasure and it’s done. My thought about Magdalena would be what that friend of mine, the ‘choro’ guy, said about the piece: to rewrite it as a native Brazilian musical. We did something similar with the works of Chiquinha Gonzaga [O Abre Alas – “Oh, Make Way,” 1998]. We picked up her beautiful tunes and added new lyrics and told her story using her themes with new words…”

Needless to say, the show about Chiquinha Gonzaga was not what I would call a “success story.” Then again, it’s been over 15 years since that project ended. The time is ripe to update the musical résumé, wouldn’t you say, by injecting something new and bold into the formula.

How about a bold, new version of Magdalena, made the modern Brazilian way? That would be an impossible dream worth having and doing! You know the old saying (updated for 2013 and beyond): “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again… No, I mean it: really, really try!”

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes