Here’s a submission to Victoria’s proposed renewal of special permission from the Commonwealth to poison dingoes:

08 October 2019

Honourable Lily D’Ambrosio MPMinister for Energy, Environment and Climate ChangeLevel 16, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, VIC 3002

cc:

The Hon Jaclyn Symes, Minister for Agriculture, VictoriaDr Sally Box, Threatened Species CommissionerThe Hon Sussan Ley MP, Minister for Environment, AustraliaRE: RENEWAL OF AERIAL BAITING EXEMPTION IN VICTORIA FOR WILD DOG CONTROL USING 1080

Dear Minister,

The undersigned welcome the opportunity to comment on the proposed renewal of special permission from the Commonwealth under Sections 18 and 18A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) to undertake aerial 1080 baiting in six Victorian locations for the management of ‘wild dogs’. This raises serious concerns for two species listed as threatened and protected in Victoria: (1) dingoes and (2) spot-tailed quolls (Dasyurus maculatus).

First, we must clarify that the terminology ‘wild dog’ is not appropriate when discussing wild canids in Australia. One of the main discussion points at the recent Royal Zoological Society of NSW symposium ‘Dingo Dilemma: Cull, Contain or Conserve’ was that the continued use of the terminology ‘wild dog’ is not justified because wild canids in Australia are predominantly dingoes and dingo hybrids, and not, in fact, feral domestic dogs. In Victoria, Stephens et al. (2015) observed that only 5 out of 623 wild canids (0.008%) sampled were feral domestic dogs with no evidence of dingo ancestry. This same study determined that 17.2% of wild canids in Victoria were pure or likely pure dingoes and 64.4% were hybrids with greater than 60% dingo ancestry. Additionally, comparative studies by Jones (1988, 1990 and 2009) observed that dingoes maintained a strong phenotypic identity in the Victorian highlands over time, and perceptively ‘wild dog’ like animals were more dingo than domestic dog.

As prominent researchers in predator ecology, biology, archaeology, cultural heritage, social science, humanities, animal behavior and genetics, we emphasize the importance of dingoes in Australian, and particularly Victorian, ecosystems. Dingoes are the sole non-human, land-based, top predator on the Australian mainland. Their importance to the ecological health and resilience of Australian ecosystems cannot be overstated, from regulating wild herbivore abundance (e.g., various kangaroo species), to reducing the impacts of feral mesopredators (cats, foxes) on native marsupials (Johnson & VanDerWal 2009; Wallach et al. 2010; Letnic et al. 2012, 2013; Newsome et al. 2015; Morris & Letnic 2017). Their iconic status is important to First Nations people and to the cultural heritage of all Australians.

Over the past two decades, ecological research in Australian ecosystems, and elsewhere in the world, has increasingly demonstrated the importance of conserving medium- to large-sized predators for ecosystem health and the preservation of biodiversity. Diminishing predator populations tend to be associated with ecosystem instability and native species decline. The extinction of a diverse suite of large carnivorous marsupials thousands of years ago (and the more recent local and functional extinctions of quoll species across much of Australia) has already simplified the structure of wildlife communities in Australia. The dingo is a keystone species that benefits small animals and plant communities by suppressing and changing the behaviours of mammalian herbivores and smaller predators (including introduced foxes and feral cats) (Johnson & VanDerWal 2009; Wallach et al. 2010; Letnic et al. 2012, 2013; Newsome et al. 2015; Morris & Letnic 2017). Their presence adds a stabilising influence and provides ecosystem resilience for species only found in Australia.

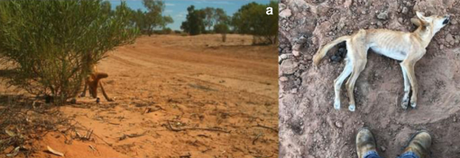

Camera-trap imagery of a wild dog triggering a poison ejector (left), and discovery of the same animal later (right). Photo by Ben Allen.

Furthermore, dingoes are listed as Threatened under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victoria) and are protected wildlife under the Wildlife Act 1975 (Victoria). However, under an Order by Council made on 18 September 2018, dingoes are unprotected on all private land in Victoria, and public land within 3 km of any private land boundary, within certain areas of the state. We underline the importance of adequate protection of dingoes within Victorian ecosystems. There are at least two distinct populations of dingoes in Australia: south-eastern and north-western dingoes. South-eastern dingoes are restricted to southern Queensland, New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and Victoria (Cairns & Wilton 2016; Cairns et al. 2017, 2018). They are threatened by habitat loss and ongoing lethal control programs, which breaks down pack structure and increases hybridisation rates with domestic dogs.

Conservation of dingoes in Victoria is therefore incompatible with continued aerial baiting.

In this context, we strongly emphasize the following points:

- The negative ecological consequences of lethal control of dingoes could seriously harm the biodiversity, resilience, and health of Victoria’s ecosystems.

- Non-lethal forms of farm stock protection (e.g., using guardian dogs and strategic fencing) have not been adequately supported and trialled as an alternative to lethal control.

- Continued lethal control of dingoes is likely to facilitate increases in ‘mesopredator’ (cat and fox) and herbivore (kangaroos, wallabies, feral goats, and potentially deer) populations that are currently managed as pests. This will in turn threaten livestock production through the spread of disease by cats (e.g., toxoplasmosis, which can cause abortion in livestock), increased fox populations (which pose a risk to lambs), overgrazing by non-stock animals (e.g., kangaroos), and suppress populations of native, threatened species.

- The extent and intensity of lethal control appear disproportionate to the small scale of the threat dingoes pose to farm stock in Victoria. Landholders should be supported to seek new measures of stock protection including electric fencing, livestock guardian animals, changes to animal husbandry, etc. before resorting to lethal control.

- Lethal control should be targeted, evidence-based, and balanced against the need to maintain ecological resilience and animal welfare. Further, there is considerable evidence that haphazard, broad-scale baiting can actually make conflict with livestock producers worse (Allen & Gonzalez 1998; Allen 2015).

- Pre- and post-baiting monitoring should be done to document the effect of 1080 aerial baiting in Victorian ecosystems and allow assessment of whether baiting programs are effective at reducing livestock predation, and hence, what the overall return on investment is.

- Concern about hybridisation is based on an ecologically unproven distinction between ‘pure’ dingoes and ecologically functional ‘dingo hybrids’. Continued use of the terminology ‘wild dog’ is not justified because wild canids in Australia are dingoes and dingo hybrids, not feral domestic dogs.

- Any justification for harming sentient beings, such as dingoes, must be subjected to the most stringent ethical and empirical standards, following concerted efforts to explore and create alternative approaches. Furthermore, the Australian public expects lethal control to be a last resort measure in attempting to solve human-wildlife conflicts.

- Lethal control of dingoes should not be done without culturally appropriate consultation with the First Peoples of Australia, some of whom consider dingoes to be a totem animal.

The proposed aerial baiting program, for which the Victorian Government has sought permission represents an unacceptable risk to remaining spot-tailed quoll populations. Spot-tailed quolls are a threatened species in Victoria and have declined in the last 20-30 years. Aerial baiting programs could pose direct and indirect risks to the quolls. First, aerial baiting programs, particularly with high-density bait distribution (40 baits/km), will reduce the dingo population and release mesopredators such as feral cats and red foxes. These mesopredators can pose a high risk to spot-tailed quolls via competition, predation, and disease transmission (Glen & Dickman 2008, 2013). The impacts of feral cats and red foxes are likely to be amplified in disturbed ecosystems, such as those being targeted by high-density aerial baiting. Indiscriminate and non-target specific lethal management should not be implemented if there is a risk to the persistence of threatened native fauna.

Second, quolls can be poisoned by aerial 1080 baits, although this might be rare (Claridge et al. 2006; Claridge & Mills 2007). Best-practice guidelines suggest that 1080 baits in quoll habitat should be buried a minimum of 15 cm below the surface. Importantly, it is not known what impact high-density 1080 aerial baiting will have on spot-tailed quoll populations, particularly in terms of sub-lethal effects to fertility, longevity and fitness.

We strongly urge the Minister to reconsider the application for 1080 aerial baiting permission in Victoria. We also urge the Minister to endorse the dingo unambiguously (irrespective of taxonomy) as ‘a threatened species of conservation priority’ and direct the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning to develop a management strategy in Victoria that preserves and protects existing dingoes (including high-content hybrids).

On the balance of scientific evidence, ethical reasoning and society-wide expectations, protection of dingoes should be enhanced rather than diminished. Aerial baiting programs are not compatible with the continued persistence of dingoes or spot-tailed quolls, native threatened species, in Victoria.

Signed:

- Professor Mike Letnic, Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales

- Dr Kylie M Cairns, Research Fellow, Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales

- Dr Damian Morrant, Principal Ecologist, Biosphere Environmental Consultants Pty Ltd

- Associate Professor Steven Ogbourne, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Professor Chris Johnson, University of Tasmania

- Rob Appleby, Director, Wild Spy Pty Ltd

- Dr Gabriel Conroy, Environmental Management Program Coordinator, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Melanie Fillios, Archaeology, University of New England, Director, Australian Centre for Commensal and Domesticate research

- Dr Justin W Adams, Biomedical Discovery Institute, Monash University

- Dr Robert Lamont, Molecular Ecologist, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Tim Doherty, Alfred Deakin Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Deakin University

- Professor Corey J A Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Fellow in Global Ecology, Flinders University

- Dr Brad Purcell, Author of Dingo, CSIRO Publishing

- Dr Arian Wallach, Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Bradley Smith, Central Queensland University

- Dr Thomas Newsome, Lecturer, The University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Mathew Crowther, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Professor Chris Dickman, FAA, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Euan Ritchie, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

- Lily van Eeden, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Dr Angela Wardell-Johnson, Environmental Sociologist, Curtin University

- Dr Georgette Leah Burns, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University

- Loukas Koungoulos, Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney

- Dr Neil R Jordan, Lecturer, Centre for Ecosystem Science, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales

- Dr Clare Archer-Lean, Author of Iconic Dingo Report 2017, School Creative Industries, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Scott Burnett, Lecturer, School of Science and Engineering, University of the Sunshine Coast