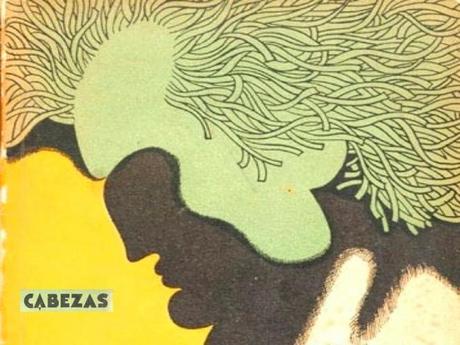

The strongest interconnection between Colombia and soccer passes through Carlos Valderrama and his mass of blonde hair. They were permed, as if to accelerate or provoke a wider commodity culture of the game of which Valderrama and his cabeza were both part. In the 1990s, a mass-entertainment industry of football knew of Colombia as a peripheral, undoubtedly avant-garde market. Specific responses were often parodic, as when Gourmont’s regular column on the Mercure de France hosted an article on American baseball (or during the futurist shows in the 1910s). Colombian soccer was generally reluctant to take risks, but in the country there was plenty of room for lower-capital dealers to speculate on budding talent, including some innovators not yet widely-known or appreciated. Championing the innovative over the academic, the playmaker’s blonde hair functioned like a salon exhibit. If one reads the way in which the Mercure de France greeted Apollinaire in 1913, it is possible to form an opinion on how to exploit and benefit from Valderrama’s tactic:

Nothing makes one think more of a secondhand furniture dealer than this collection of verse published by M. Guillaume Apollinaire under the title, at once simple and mysterious, of Alcools. I say secondhand furniture dealer because a litter of incongruous objects have been discarded into this slum, some of which have value but none of which is the product of the merchant’s own industry. Precisely there is one of the characteristics of the secondhand trade: it resells but does not manufacture. . . In the massing of objects a colorful and dizzy variety takes the place of art. With difficulty one can perceive, through the holes of a shabby chasuble, the ironic and ingenuous look of the dealer, which is at once that of the Levantine Jew, the South American, the Polish gentleman, and the facchino [porter].

The writer of this attack, Georges Duhamel, is uncomfortable enough with a bohemian poet to imagine a foreign-sounding “southern” background to drop his humiliating tale of immigration and Jewish diaspora. Valderrama’s tricksterism, however, was never merely a matter of personal style. It also reflected an awareness that humorist appeals would save Colombia from silence and would provide him with the widest possible audience. His permed hair and slick passes were to become an advertising poster for an entire country—all mutually interdependent.

If you like Valderrama, then you are likely to enjoy cheap reproductions of circus masters, or, like Apollinaire, you have a taste for an electric chandelier with bulbs made to look like sea urchins. There is a certain playfulness in Colombian soccer that carries some of its activities and attitudes into the realm of art. It engages the idea of artistic fakes. Before addressing a broad public, instead of lamenting an episode of plagiarism, it simply places the little word nach (‘in the manner of’) before the performance. It is no wonder that Valderrama’s fullest articulation of his concept of avant-garde soccer performance is to be found in his appearances with the national team of Colombia. Like a Nietzschean “active nihilist,” the avant-garde footballer responds to a meaningless world by forging his own divinity. Valderrama’s cabeza enumerates the elements, the details. His brutality is also capable of graciousness. He orders the midfield universe in accordance to his personal requirements of speed, and, in so doing, he facilitates his relations with his fellows—if only for a moment. ♦