Steve and I went yesterday to a local Episcopal church again, as we observed the third Sunday of Advent. Friends have repeatedly invited us to this church, too — one who's a recovering Southern Baptist, another who's the son of a United Methodist minister. One female, the other male; one straight, the other gay; one a former student of mine in a graduate ministry program, the other a longtime friend.

As I shared with my Facebook circle of friends, the gospel text was the text in Luke's gospel in which John the Baptist denounces those coming to him for baptism as a brood of vipers insofar as they seek his baptism but do not intend to turn their lives around. I'm always intrigued at how many Christians today bear down hard on their obligation to preach a message of repentance to gay people — "It's because we love you so much," they often say, or "Truth trumps love, and love without the hard truth that you're a sinner destined to hell is not love at all" — but who completely ignore the inconvenient facts that 1) the gospels never once mention homosexuality, and 2) the gospel texts that do speak of repenting talk about reordering our priorities in such a fundamental way that we turn completely around (this is what the word metanoia, which is rendered "repentance" in the English translation of the gospel texts, means).

John tells the crowds coming to him for baptism to repent of their greed — "If you have two shirts or more food than you can eat, share half of what you have with those in need" — or to repent of their oppression of the poor — "You who are tax collectors, stop your extortion" — or to repent of bearing false witness against others — "Don't accuse people falsely."

The message of repentance preached by many contemporary Christians is curiously truncated, isn't it? It's focused on what's not mentioned in the gospels at all — the sin of those convenient gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender others we've managed to run out of our churches, in any case — while it totally overlooks our sins, the sins that constantly roil our own lives and hearts, and are to be found everywhere in our midst.

The priest who delivered the sermon we heard yesterday zeroed in on John's image of a brood of vipers. "We become broods of vipers," he said, "when we let the asps in our hearts raise their heads and hiss as we target those different from ourselves — perhaps those of different religions or nationalities — while we ignore our own moral failings."

And then he said (I'm reporting faithfully what I heard without quoting literally): "When the president of a Christian university encourages Christian students on his campus to arm themselves against Muslims, he's encouraging them to behave like a brood of vipers, and is defining the rest of us who are Christian as a brood of vipers."

Steve and I continue to find a welcome in the Episcopal churches we're visiting that is totally lacking in our Catholic community. It was — well, it was moving — at the coffee hour following liturgy to have one person after another who knows us come up and welcome us to the church, and tell us we'll find a loving and supportive home as a gay married couple in this church.

I can't imagine this happening to us in any local Catholic church. For that matter, I can't imagine hearing the kind of sermon we heard yesterday, with its candor about what's happening in our world today connected to an Advent text, in any local Catholic church. Priests in our diocese who have made "political" (i.e., non-Republican) points in homilies in recent years, including the pastor of the parish to which my brother and his family went, have found themselves severely punished for doing so. They can preach until the cows come home about abortion and same-sex marriage, but please don't mention war and peace or immigrants: those are "divisive" issues, our local Catholic priests are told.

I'm glad to know some Christian leaders are speaking out about what the U.S. is in danger of doing to itself when it allows the voice of someone like Donald Trump, with his ugly pronouncements of hate and bigotry, to be normalized. I'm glad some Christian leaders are speaking out to remind the public square that what Mr. Trump says does not represent the rest of us who are Christian.

I'm grateful to Nicholas Kristof, a journalist who is also a practicing Catholic, for saying the following this weekend in the New York Times:

In fact, religion is invariably a tangle of contradictory teachings — in the Bible, the difference between the harshness of Deuteronomy and the warmth of Isaiah or Luke is striking — and it's always easy to perceive something threatening in another tradition. Yet analysts who have tallied the number of violent or cruel passages in the Quran and the Bible count more than twice as many in the Bible.

There's a profound human tendency, rooted in evolutionary biology, to "otherize" people who don't belong to our race, our ethnic group, our religion. That's particularly true when we're scared. It's difficult to conceive now that a 1944 poll found that 13 percent of Americans favored "killing all Japanese," and that the head of a United States government commission in 1945 urged "the extermination of the Japanese in toto."

And I'm grateful to the national interfaith network PICO (People Improving Communities through Organizing) for issuing the following statement in a just-published letter to American Muslims from evangelical leaders:

We are concerned that this rhetoric creates fear and uncertainty for our Muslim neighbors. We understand that there are deep political motivations by presidential candidates this election cycle to use Muslims as a source of fear to get votes. We also understand that a majority of mass shootings are committed by white men, but white communities do not face the same responsibility of collective condemnation and backlash that Muslim communities face.

To our Muslim brothers and sisters: We see you. You are our friends, our coworkers, and our allies in building a better country where every person is valued. It hurts us that your membership in this country is being questioned. And so we are reaching out to express solidarity with you during this difficult time (emphasis in original).

In particular, we want to reach out as a group of PICO clergy and staff who come from the evangelical Christian community. To our shame, some of this anti-Muslim rhetoric is coming from leaders who identify as evangelical Christians. Most recently, the president of Liberty University responded to the tragedy in San Bernardino by telling students to get concealed gun permits to "end those Muslims."

And, finally, I'm grateful to Troy Jackson of the Amos Project for making the following statement:

As an evangelical Christian, I've finally come to the sad conclusion that the public rhetoric of the current CEO of the Billy Graham Association is nothing but a #GrahamShame. . . .

Just as Muslims do not want to be defined by those who pervert their faith by hateful rhetoric and acts of terrorism and destruction, I only hope that others do not judge all Christians based on the hateful and exclusionary rhetoric and violence of a few Christians.

Therefore I proudly joined with other Evangelicals in PICO to pen the following statement: Standing Together Against Anti-Muslim Rhetoric. I am also really sad that such statements are necessary.

We cannot just shake our heads and decry this #GrahamShame. As Christians, now is the time to act by reaching out to support and love Muslims in our midst, just as Jesus calls us to do.

Advent, or snowflakes on Starbucks coffee cups, or Christmas manger scenes, mean nothing at all if we remain utterly silent as hate rears its ugly head in our midst and hate speech — in the name of Christ — becomes normalized while we're too busy keeping Advent and preparing for Christmas to speak out.

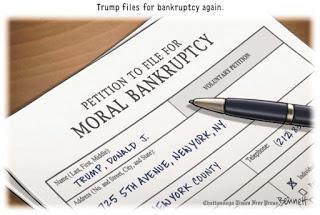

The cartoon at the head of the posting is by Clay Bennett at Truthdig.