Henry Kissinger wrote a 624-page book, On China. Here’s a shorter take.

China’s imperial dynasty was overthrown in 1911. Violent turmoil followed as warlords, Communists, and a government led by Chiang Kai-shek all battled for power. Then Japan’s 1930s invasion ravaged the country. Finally in 1949 Mao’s Communists triumphed; Chiang and his Nationalists decamping to Taiwan. Which became prosperous and democratic; de facto independent, though China insists it’s theirs.

Poverty always afflicted China. Mao’s harebrained economic policies didn’t help. The 1958-62 “Great Leap Forward” left tens of millions dead. The country was convulsed yet again in 1966 by the madcap “Cultural Revolution” Mao launched to consolidate his control. Destroying much cultural heritage, and many more lives. Ending only with Mao’s 1976 death.

That history of traumatization shapes China’s psyche. Mere domestic order seems a great blessing. Chinese also keenly feel past humiliation, seeing a century of Western bullying and exploitation. Making them truculently nationalistic, with chips on their shoulders, something to prove, swaggeringly aggressive.

Deng Xiaoping succeeded Mao, jettisoning his craziness and most communist dogma, opening up the economy. While big state-owned enterprises endure, they accompany a private sector actually epitomizing “unfettered laissez faire capitalism.” Producing four decades of spectacular economic growth, eliminating most Chinese poverty and creating a vast middle class. For which they also thank the regime.

Younger people, especially, wanted a freer society too. But that dream died with the 1989 Tiananmen bloodbath. All memory of which the party has striven to scrub out. The basic deal it offers is rising prosperity in exchange for total political control.

Corruption and dishonesty have long characterized China’s culture. In 2012 Xi Jinping became leader, gaining plaudits for an anti-corruption campaign. But it was mainly a way to amass more personal power than anyone since Mao. China actually remains deeply corrupt. While Xi has suppressed all dissension or debate, deploying pervasive propaganda and an Orwellian surveillance state. Thus China’s repression in Tibet, then Xinjiang, then Hong Kong. A million Xinjiang Uighurs are in concentration camps, an effort to pretty much stamp out their Muslim religion.

Today the idea of democracy has scant traction. What freedom Chinese do want is economic, which they’ve got. Politically most seem happy with dictatorship, if (as they believe) it manages the country well. In fact, they take pride in their system’s achievements, rejecting “Western” values like rule of law or press freedom, and feeling superior to democratic nations as dysfunctional, disordered, and declining. They support crushing Hong Kong’s democratic aspirations. Some social liberalism does surface mainly among the young, for causes like women’s equality, LGBT rights, and the environment. But most Chinese are more into consumerism and other personal stuff than public affairs. And remember that China has no historical ethos of individualism like ours, conformism being more the rule.

Also greatly shaping Chinese society is the one-child policy, harshly enforced between 1980 and 2016, to prevent overpopulation. It succeeded too well, causing a shortage of working age people. While a traditional preference for boys meant many girls aborted, with lone boys raised as spoiled princelings, and not enough females for them to marry. Add in desperate competition for university slots and housing costs becoming unaffordable, another damper on marrying.

Many millions had migrated from farms to cities for better pay, but the “hukou” system prevents their registry as official residents there, making them second class citizens. A deep social division. Meantime sweatshop factory jobs are disappearing, moving to even lower wage countries. Now many Chinese feel they’re in a rat race with “996” office jobs — 9 AM to 9 PM, six days a week.

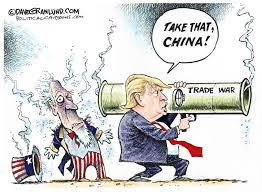

There’d been hopes that an increasingly prosperous and secure China would become a well-behaved member of an interconnected global community. But clearly today’s China thinks differently. If Trump was right to see China more adversarially, unfortunately he followed up brainlessly, subverting our own interests. Not just with self-harming tariffs, but trying to decouple our economy from China’s, dividing the world into two economic ghettoes with separate supply chains, to our detriment. Particularly idiotic was confronting China alone, blowing off our allies who could have been marshaled into a united front.

But this needn’t be a new cold war. Whereas Soviets wanted the whole world Communist, China has no such agenda, being “Communist” in name only. Seeking instead just national aggrandizement. Mere cost-free kowtowing could actually help assuage that. What we really have is not combat but competition, and there’s a big difference. Competition among economic actors is always the way of the world, and should be, it’s the essence of our own free market system. The world is not zero-sum with China’s gain necessarily being our loss. They don’t stupidly imagine destroying America would be advantageous. We have to manage our competition for mutual advantage.

Of course that doesn’t mean overlooking China’s intellectual property theft and other unfair tactics. Just as we enforce rules within our own economy and punish violators but don’t seek to put them out of business. Nor do China’s human rights violations make it our enemy. That too we must call out, and mitigate whatever way possible; but again, that needn’t mean blowing up what’s mutually beneficial in our economic relationship.