Yes — another droplet spit into the vast ocean of verbiage on this topic.

We think shooters are nut cases. Obviously they’re not normal. But “mental illness” is too simple a label.

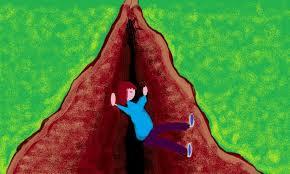

Start with this: “No man is an island.” Though we are, in a physical sense, separated from each other by impenetrable physical barriers. So could you be fine living in isolation from all others, if that suited you? But it almost never does suit — because our long pre-history of living in groups, and surviving by group cohesiveness, programmed our genes for communal living. That’s the import of “no man is an island.”

And someone who feels they’re an island — marooned there involuntarily, exiled there — keenly feels a need to do something about it.

I’ve been reading Francis Fukuyama, a political theorist, one of whose key themes is the universal thirst for recognition — that is, other people acknowledging your dignity and worth. Situating you within that cocoon of social integration. It’s a key driver in political life. And here again, to feel excluded from that roils one’s psyche.

This is largely a problem of modernity. Earlier societies were organized in such ways that it was really impossible for anyone to be an invisible island. Modern societies are more atomized; we are much less embedded in all-enveloping social constructs, much more on our own. Nevertheless, the evolution-instilled human social instinct is still so strong that most people find ways to express it and live connected lives. But some do fall between the cracks — making it a painful challenge to find meaning in their lives.

We recently viewed a documentary about a young man named Tyler Barris, who epitomized this. Comprehensively a loser, not just unable to find a societal role through work, but bereft of human connections. He tried unsuccessfully to become a star video game player. A sometime girl friend was interviewed, but their relationship seemed ephemeral.

Barris was not a mass shooter. Instead, he found he could achieve “evacuations” by “swatting.” Mostly just calling in false bomb threats and then reveling in the news coverage of the resulting evacuations, and the attention he got on Twitter. One time he targeted a TV news station itself. It gave him the sense of being able to control something that mattered in the world; a way to make himself matter. Make himself seen (he didn’t really try to stay hidden). Even though others were not seeing him as a human being of dignity and worth but, rather, a little prick. But that was better than nothing.

Barris shrugged off a brief jail sentence. He started doing swatting gigs for hire by other losers. One involved a 911 call summoning police to a supposed hostage situation in someone’s home. A man was shot dead; triggering two later suicides. Barris, hardly bothering to cover his tracks, got twenty years.

His kind of mentality may provide some insight into the heads of mass shooters too. Who decide that’s the only way to make themselves matter to other people. Even while others don’t actually matter to them, as people. We call that psychopathy. Certainly true of Barris.

While psychiatric intervention might help, this seems more a problem for social workers. To identify people suffering from this syndrome, working to counter their feelings of isolation and insignificance. But that’s a very tall order indeed. It goes with the territory that such people are “under the radar” — unseen. (Until it’s too late.)

Of course this is not a total explanation for mass shootings. And focusing on mental health is a distractive refuge for those who’ll do anything to avoid truly addressing our gun violence problem. All the mental health efforts in the world would barely nibble at the social pathology described here.

But we could readily make it much harder for its sufferers to get guns. Especially guns whose only purpose is killing a lot of people fast. Our allowing anyone to buy such guns is insane.

Now that’s a real mental health problem America has got.