Today, many attribute the box office failure of Alfred Hitchcock's 1949 opus Under Capricorn to it not being a thriller. That, obviously, is true, but the stiff-upper-lipped love triangle is nevertheless mysterious. Set in colonial Australia, Under Capricorn moves through a world of ex-convicts, where people cut off any attempt to suss out the crimes that sent other people there, lest someone eventually come question them, too. And because the characters must sit in isolation of each other, gestures of concern and caring get interpreted as secretive, self-serving actions, while manipulative ones are dismissed as nurturing.

Today, many attribute the box office failure of Alfred Hitchcock's 1949 opus Under Capricorn to it not being a thriller. That, obviously, is true, but the stiff-upper-lipped love triangle is nevertheless mysterious. Set in colonial Australia, Under Capricorn moves through a world of ex-convicts, where people cut off any attempt to suss out the crimes that sent other people there, lest someone eventually come question them, too. And because the characters must sit in isolation of each other, gestures of concern and caring get interpreted as secretive, self-serving actions, while manipulative ones are dismissed as nurturing.Though it opens with a series of largely static, talky takes, Under Capricorn rapidly establishes itself as not only a Hitchcock film but one of his most immediately identifiable. The long-take structure he used as an ingenious formal experiment in Rope is here subsumed into a florid melodrama, constantly emphasizes the freedom and restrictions of movement within the tucked-away, Gothic house where most of the action takes place and embodying the stiff mannerisms of the strict, willfully oblivious social codes that dictate behavior among the characters.

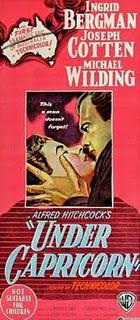

The initial stiffness of the camera matches the ostentatious decorum new governor's arrival, an occasion he treats with all the pomp and circumstance of the position but the general population views with disinterest. The action shifts to the governor's cousin, Charles Adare (Michael Wilding), a brash young man who clearly shares more with the more laid-back Australian colonists than his uncle's stuffy ways. He soon learns of the locals' reticence to discuss private matters, even when he learns he has an acquaintance on the continent. Sam Flusky (Joseph Cotten), an ex-con turned thriving businessman, meets Charles and, in the process of courting the governor's cousin for business reasons, learns that the Irish lad knew his wife, Henrietta (Ingrid Bergman), a woman who has fallen into debilitating alcoholism. Looking to cheer her up and perhaps snap her out of her insular stupor, Sam invites Charles to his house.

What follows is a rigidly controlled melodrama that intertwines Hitchcock's sense of cold mastery with the bottlenecked passion of restrained emotion. Ingrid Bergman's entrance instantly shifts the mood of the film, her elegant entrance belying the swirling agony rolling off her in waves. The dry period construction remains, but suddenly Hitchcock begins delving into it with his graceful long takes and clever framing. When Henrietta sits down, clearly drunk to the point of incoherence, Hitchcock frames her between two lit candles, illuminating her and visualizing the burning moods within her. When Hitch reverses to show Cotten, farther away, the look of barely hidden agony and shame on his face gives those flames an entirely different meaning, far more somber and wasting. Cotten looks consumed by grief from the moment Bergman enters the screen, and as that pain finally morphs into frustrated fury as his wife does not return to him. Worse still, the tether Charles provides to happier times draws Henrietta closer to the newcomer as Sam finds himself forced to choose between his wife's happiness and his own.

Hitchcock slyly incorporates some of his more usual tropes into this drama: when Charles arrives at the Flusky home, no one answers the front door, so he roams around the side as the camera tracks in one take, stopping at a window and looking in as the maids viciously fight over accusations of their criminal pasts. Effectively, Hitch gets to have his voyeuristic moment (spying on a catfight, no less) even while the movie is still locked in its more starched initial mode. Echoing Rebecca, a dark secret tugs at this married couple, and a deranged, jealous maid (here played to marvelously sinister effect by Margaret Leighton) who pretends to help the wife but has her ulterior motives. The house itself looks, on the outside, like a Hanover version of some Gothic castle on a barren Transylvanian hill, a mood Hitchcock would later mine for the family home overlooking the Bates motel.

These are not plot elements Hitchcock shies away from, and he even emphasizes the sinister air in the climax when he uses chiaroscuro lighting for the reveal of the reason for Henrietta's self-medicated sorrow. Yet Hitchcock channels all of this into the emotions of the story, which only become more rending as the movie progresses. When Henrietta comes clean to Charles, the camera stays back to look at her over Charles' shoulder, not only avoiding the cheap impact of a close-up monologue but letting us see her in terms of how the characters' perception of her shifts with the confession. After demonstrating that his capacity for manipulating audiences could be used in much more heartrending terms with his masterpiece Notorious, Hitchcock softens the savagery if not the sadness. And by showing Charles in the frame as Bergman has her deflated monologue, he reminds the audience that everything in this film, its secrets, revelations and emotional fulfillment, is secondary to the manner a person is perceived by others, and that even with someone she loves, Henrietta will never have the freedom of expressing something without being judged for it.

Under Capricorn reminded me of Martin Scorsese's The Age of Innocence, in that a break in typical setting and subject matter for a director known for technical wizardry and active camerawork ultimately provides a different context that, if anything, clarifies key themes and stylistic tics. If Scorsese's film brought out his usual ideas of characters driven in spite of themselves to deprive themselves of happiness and calm, Hitchcock re-frames a mystery around a sense of proprietary confinement. A sense of doom hangs over the final act, not so much regarding the question of whether Milly will be able to get Sam for herself but the matter of the governor's response to admissions that clear some and incriminate others. The official's disgust over the whole thing suggests that whether the characters get themselves off with the truth or falsification, he merely wants them out of his social sphere where he need not dwell upon such distasteful matters. The steps he takes to ensure he does not have to hear anything more on the matter are not shocking, merely heartbreaking in their coldness and adherence to insipid appearances over human effect. For a director so often criticized for his own emotional remove, Under Capricorn almost seems like autocritique even as it utilizes Hitchcock's style to craft one of his cruelest, in terms of the connection one makes to the characters and the hope that engenders to see a happy ending. One of the finest examples of the master's genius.