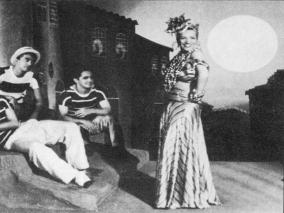

Young Carmen Miranda (chickflicksmusical.blogspot.com)

From Porto to the Port of Rio

Amazingly enough, Bidu Sayão was a close contemporary of another popular Brazilian entertainer: the exceptionally gifted Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha, better known by her professional name as Carmen Miranda.

Born in the town of Marco de Canavezes, district of Porto, in Portugal on February 9, 1909, Carmen came to Brazil, along with her mother and older sister Olinda, when she was not yet one. She grew up in the city of Rio, at about the same time that Bidu was learning to climb trees in her backyard.

Her parents dubbed her “Carmen” (thanks to her music-loving uncle Amaro) in honor of the Spanish protagonist made famous by Georges Bizet’s opera of the same name, or so the story goes. Otherwise, her connection to the art form was minimal, if non-existent.

She was not, as some of the early publicity about her indicated, the offspring of a well-to-do family. Quite the contrary: her father, José Maria Pinto da Cunha, who arrived in Brazil ahead of his clan, was of no discernible profession, although his background as a farm hand apparently telegraphed his low-born status. His main sideline, however, was as a barber. Out of necessity, her mother, Maria Emilia, became a laundress in Rio. She later managed a boarding house there, all to make ends meet.

But whatever the family’s financial condition had been, the naturally plucky and irresistible personality that characterized the young Portuguese immigrant was already in evidence. Little Carmen left no doubt as to what her future aspirations might be: she would tell anyone within earshot that she was predestined by the entertainment gods for a career in the movies.

Like most working-class youngsters in Brazil at the time, she was forced to quit school at an early age to go into the business community, holding down a variety of low-paying jobs, including one as a chatty hat-maker, and another as a “singing” store clerk, which resulted in her being castigated by her boss for deliberately distracting her fellow co-workers.

Video Killed the Radio Star

Luckily for her (and for the Brazilian labor market), Carmen was snapped up by several local radio stations, among them the widely heard Rádio Mayrink Veiga, after simultaneously cutting her first records for the Brunswick label in September 1929. Her first big hit, however, was the march tune “Taí, eu fiz de tudo pra você gostar de mim” (“You see, I did everything to make you love me”), recorded in January 1930. She eventually landed a contract with RCA Victor, later with Odeon-Brazil and American Decca.

Other song numbers followed in quick succession, including the best of such acknowledged songwriters as Assis Valente, Lamartine Babo, Joubert de Carvalho, and Synval Silva. Her large recorded repertoire of popular songs, ditties, march tunes, sambas, tangos, and other more obscure material from the period would reach into the literal hundreds.

Some revisionist authors have tried to describe her early singing style as a carioca version of Elvis Presley — that is, of a poorly educated white person with a modicum of musical talent, who just so happened to have incorporated the soul and substance of African descendants into her entertainment vocabulary and, in the process, made them virtually her own.

Carmen in the 1920s (arteeculturabrasil.blogspot.com)

While the jury may still be out on Elvis, it was an unfair indictment in the case of Carmen Miranda. In the first place, she was neither poorly educated or untalented, nor was she a “pale” imitator of a prevailing ethnic trend; and in the second, the growth of marcha, chorinho, maxixe, and modinha – and especially samba during Carnival time – had already spurred many of Brazil’s native-born composers to write down and interpret these myriad forms as far back as 1915, most strikingly by composers Ernesto Nazareth, Francisca “Chiquinha” Gonzaga, Pixinguinha, and Heitor Villa-Lobos,* to name only a few, and still later by the likes of Noel Rosa, Ary Barroso, João de Barro, and Dorival Caymmi.

Carmen’s particular genius was in taking the basic raw material found in this multitude of musical styles and thoroughly reinvigorating the form: by applying to it her own unique blend of crystal-clear vocalism, rapid-fire verbal patter, and razor-sharp rhythm. This would ultimately lead to her creation of a black-white composite of the streetwise baiana figure, an endearing (and somewhat stylized) cultural by-product of Northeastern Brazil accessible to even the most sophisticated of theater-going audiences.

She would develop this character further in her later domestic and Twentieth Century-Fox film work, but for now she strived hard to concentrate on her nightclub routines with younger sister Aurora, an equally talented sibling with artistic aspirations of her own. The two of them would appear frequently throughout the 1930s at the Cassino da Urca in Rio, usually backed by the Bando da Lua (“The Moon Bunch”) combo and other guest performers.

Such bubbling effervescence as Carmen seemed to exude should have been a veritable shoe-in for the budding Brazilian film industry; and, true to form, she soon appeared in her first feature, the documentary O Carnaval Cantado de 1932 (“The Carnival Sung in Rio in 1932”), although she herself sang in only one musical number, “Bamboleô” by André Filho.

A Voz do Carnaval (“The Voice of Carnival”) was released the following year, along with Alô, alô Brasil (co-starring Aurora) and Estudantes (“Students”), co-starring popular radio singer Mario Reis, both from 1935; Alô, alô Carnaval (1936) with an all-star cast headed by Francisco Alves, Dircinha Batista, and Barbosa Júnior; and the mega-production Banana da Terra (“Fruit of the Earth,” 1939), where Carmen introduced Brazilian moviegoers to her now-famous Bahian alter ego.

Carmen in Banana da Terra (ccpg.puc-rio.br)

All if not most of the examples cited above of early Brazilian cinema have been lost or, more correctly, deteriorated over the years due to exposure to the elements. Only a small fragment of Banana da Terra remains, showing a youthful Carmen Miranda, surrounded by striped-shirted male dancers from the Urca Casino nightclub, strutting her stuff, as it were, in composer Dorival Caymmi’s “O que é que a baiana tem?” (“What does the Bahian have?”). Carmen took her cue (as well as her costume design) from the song’s lively lyrics, which describe the native baiana’s outfit and accessories in excruciating detail:

O que é que a baiana tem?

O que é que a baiana tem?

Tem torso de seda, tem (tem)

Tem brinco de ouro, tem (tem)

Corrente de ouro, tem (tem)

Tem pano da Costa, tem (tem)

Tem bata rendada, tem (tem)

Pulseira de ouro, tem (tem)

Tem saia engomada, tem (tem)

Tem sandália enfeitada, tem (tem)

E tem graça como ninguém…

Como ela requebra bem…

What does the Bahian have?

What does the Bahian have?

A torso of silk she has (yes)

An earring of gold she has (yes)

A necklace of pearls she has (yes)

The finest of jewels she has (yes)

A gown made of lace she has (yes)

A bracelet of gold she has (yes)

Her dress is superbly pressed (yes)

Her sandals the very best (yes)

And charm like no other has

So like the baiana’s have

During one of her many flamboyant performances at the Urca, the legend goes that visiting American impresario Lee Shubert became smitten with Carmen at first sight and decided to hire the flashy entertainer “on the spot” for his Broadway mounting of The Streets of Paris, to premiere in New York in the autumn of 1939. In actuality, Shubert had been receiving frequent communiques about her talent for many months prior to his actual arrival in Rio. What he saw on the night of February 15, 1939, at the Cassino da Urca, convinced him that previous reports of her extraordinary abilities had not been exaggerated (even if he understood little of what she was singing).

The stage was now set for the Hollywood phase of Carmen Miranda’s showbiz career — a midstream course correction neither as readily accepted, nor as openly welcomed, by fellow Brazilians as her “O que é que a baiana tem?” period.

(End of Part Two)

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes

* Before that, even budding opera composer Carlos Gomes had gotten into the “act” with his dedication of an 1859 modinha, “Quem Sabe?” (“Who Knows?”) – known by its famous opening line, “Tão longe, de mim distante,” or “So far, and from me so distant” – to one Ambrosina Corrêa do Lago, reported to have been the first love of his life.