My friend and prolific blogger Steve Wheeler issued an interesting blogging challenge the other day called A Twisted Pair. He proposed taking two different people with no apparent connection and writing a post about learning that somehow connects the two, which I thought was an interesting idea. Steve proposed a few possible pairs of names on his post to get our ideas started, and although there were many pairings that intrigued me, two that really stood out were both people who have always inspired me – Pablo Picasso and Sir Tim Berners-Lee. So here goes…

There are probably numerous ideas to explore in terms of how the concepts of learning are embodied by these two people. I’ll try to begin with the obvious and then see if we can find other connections.

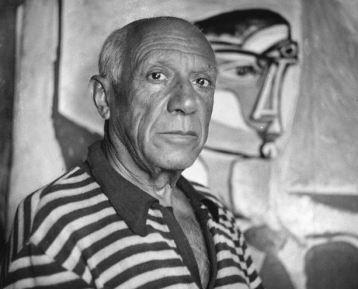

Let’s start with Picasso. Picasso was an incredibly prolific Spanish artist with a body of work that is profoundly extensive. Over the years his work moved through multiple phases where he would latch onto an idea, explore and delve deeply into it, allowing it to morph and change until he seemed to have wrung every possibility from it, then a completely new idea would emerge and the process would begin all over again. His early work of the Blue and Rose periods shows incredible artistic talent, and his later work deeply explored ideas of construction and deconstruction, leading to many of the Cubist works for which he is most famous. Picasso had an incredible ability to see the world through the eyes of a child, to find the core essence in complex things, and to simplify them down to their essentials. Despite never actually being a teacher himself, these traits have been present in every great teacher I’ve ever known.

It takes a true spirit of curiosity and invention to let your ideas drift and morph from one to another, and a brave indifference to failure when some of those ideas inevitably fail to bear fruit. Again, the parallels with learning are strong. The idea that all progress is ultimately reliant on trying new things and tolerating failure, rather than achieving total perfect execution. To learn you must be prepared to fail a lot. And to fail a lot you much be prepared to try a lot of new things. There are many important learning concepts embodied in this simple idea – that learning is a process of iteration, of trial and error, of feedback and feedforward, of allowing ideas to flow uninhibited from one insight to the next, all fed by childlike curiosity and endless wonder about “what if?”

The other person in this twisted pair is Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web. I read his biography, Weaving the Web, many years ago and found it to be a fascinating insight into his curious, creative spirit and his selfless approach to designing a system that was simply aimed at making the world a better place. The impact of the WWW on humanity has been absolutely seismic, and will probably be seen as the single most influential invention of all time. I think you could argue that the Web has redefined pretty much everything about the way modern society works, yet someone less altruistic than Berners-Lee could have easily tried to build in a system of monetisation to the very core of the way the web works. Berners-Lee invented the idea of a URL – a Universal Resource Locator – where every webpage, every image, every video, every online asset, has a unique location, and could be expressed in a way that every computer could understand. This was a revolutionary idea. But imagine a world in which the notion of a hyperlink was protected by a patent, and every click on the web would earn a small royalty payment for its inventor? With the “patent wars” played out by just about every big tech company these days, this is not hard to imagine. Had Berners-Lee maintained the intellectual property rights to the web he invented he could have been richer than Bill Gates and God combined. But he didn’t. He quite deliberately didn’t. He saw the web as something that was for the greater good of humanity, and placed that goal ahead of any desire to get rich from his idea.

There are a few learning principles that resonate with me about Sir Tim. Openness. Sharing. Altruism. A desire to build something simply to make the world a better place. As Eric Schmidt once observed, “If [computer networking] were a traditional science, Berners-Lee would win a Nobel Prize”.

When I think of the greatest teachers I know, and the most engaged learners I know, they seem to embody certain characteristics. I think that both Picasso and Berners-Lee show some of these characteristics in different ways.

First, from Picasso, is the ability to take information from multiple sources in a variety of ways and reinterpret them as your own. To “steal like an artist” if you will (a phrase often incorrectly attributed to Picasso). To allow yourself to absorb influences and ideas from all over the place, and have them percolate through your mind, being processed and critiqued and changed along the way, emerging as completely new ideas and understandings. There is no such thing as learning in a vacuum, much as there is no such thing as creativity in a vacuum. Everything is a remix. Every idea is borrowed from somewhere. When you immerse in this kind of creative learning process, the end results are often unrecognisable from the influences that formed them. This morphing process is, as Stephen Johnson says, where good ideas come from. And I will add, where good learning comes from. I can think of no better person to embody this idea of learning through the growth of ideas than Pablo Picasso.

The second important aspect of learning is the idea of learning for it’s own sake. Learning should be worth doing, not just to get a grade or pass a test or get a certificate, but because the simple act of learning is intrinsically valuable in and of itself. Curiosity and wonder should be their own rewards. Building and making and tinkering, be it with ideas or actual physical objects, does not need to be formalised with rewards. I think Berners-Lee embodies this idea, in the unselfish way he started out by trying to solve a fascinating problem just for his own personal benefit but quickly realised it had a much broader application, and he was willing to just give it away because it felt like it was the right thing to do, and that it would help many people. Like the invention of the Web, the best learning is usually done simply because it is worth doing, with or without a reward at the end.

These are my learning lessons from Pablo and Tim.

Wonder. Be curious. Make. Grow. Share.

Just because.

Header image from Wikipedia

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Twisted_pair