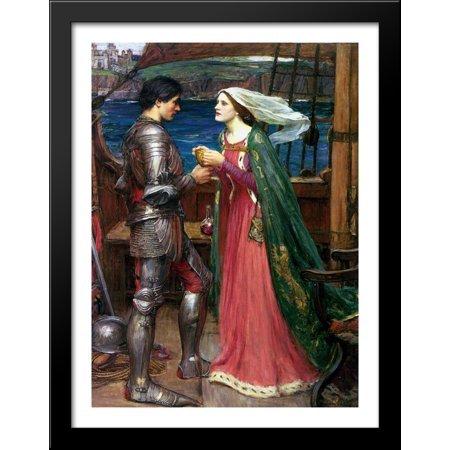

Tristan and Iseult, Tristan and Isolde, Drustan and Yseult… the variations of spellings are endless, but the way the names – and the story – roll of the tongue, largely stay the same.

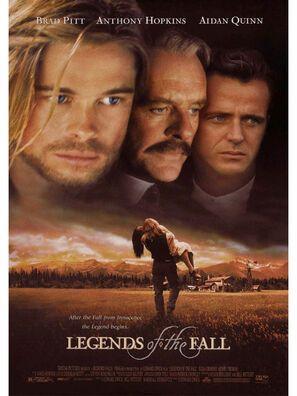

I didn’t read the story growing up, but I gathered the main plot points throughout other literary references my whole life. The story was built slowly, for me, an allusion here, a quip there, until when I watched Legends of the Fall for the first time in college, I thought I understood the the gist of the movie’s genius: naming the wild heart that could not be tamed “Tristan” and subtly throwing in that his wife’s name was Isabel.

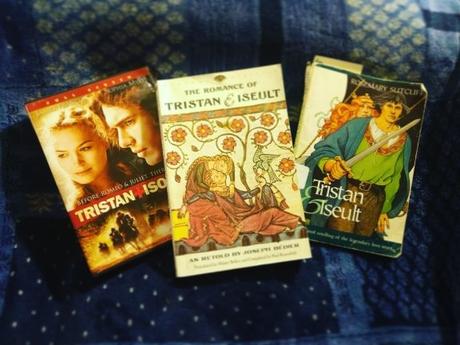

The movie is based on a book by Jim Harrison, that I later read and was not so smitten by, I even wrote a less than glowing review here. But in finally reading Tristan & Iseult both to myself and aloud to my daughter, I’m finding the desire to re-read Jim Harrison’s novella swelling in my literary soul.

The part that never sunk in through other literature, or the heavily influenced King Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot love-triangle–the part that left me briefly chuckling in a “Oh I see what they did there” –was that there are TWO Iseults. (And *spoiler* Tristan’s wife in Legends of the Fall is known as Isabel Two.) The story of Tristan and Iseult follows the tale of Tristan falling in love with Iseult the Fair, Queen of Cornwall, but marrying another Iseult, called Iseult of Whitehands. If you wanted to twist literature and try to be one of those people who got extra creative, telling authors what they were really trying to say and all that, you could say the wild-hearted Tristan had mommy issues and was Oedipally in love with the first Isabel. But that’s just too much…

The point is that literature is pervasive, ancient poems permeating society for generations; legends evolving and growing, but also maintaining. The stories of Tristan & Iseult, in all their incarnations, heavily influenced the King Arthur tales, the theme or forbidden love–no matter how ridiculous–ending in passionate death (Romeo and Juliet, anyone), continue for centuries. Bits and pieces dribbled in to make each new story more rich with nuance and the truths behind the human condition.

So, I found the most “original” version I could find (and still read in English) for myself, and the most kid friendly version for me to read out loud for my eight year old. Rosemary Sutcliff is my go-to when it comes to ancient or medieval tales brought to life for a young audience. Much to my pleasure, she had a Tristan & Iseult published in 1991. Kiddo gave the story 4 stars on Goodreads, “It was really amazing, but also dramatic, and all the love stuff isn’t what would really happen.”

We had many discussions on the difference between love and passion. “Love is patient, love is kind, love does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud, love is not rude or self seeking. It is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrong. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices in the truth…” A man who loves you will never encourage adultery. A woman who loves a man will not participate in adultery. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices in the truth. Cheating isn’t love, it is passion. Some romance can be romanticized too much. It’s not that the “love stuff isn’t what would really happen,” it’s that it would happen, it does happen, and that’s not love, that’s agonizing obsession.

I enjoy working through literature with her. When she’s in college, I’ll be interested to see what her much more informed reaction will be to Legends of the Fall. As soon as my library is out of storage, I plan to re-read a few things, and see if my own mind has been changed by the experience of reading the literature that came before.