There’s an old style expression, which I’m sure you’ve heard. “You have to know the rules before you break them.” I’ve always thought the adage is meaningless – if you’re going to ignore the rules anyway, what’s the point of knowing them? The phrase makes a bit more sense, however, when you see photos of how stylish men dressed when they were young. There are a dozen examples to be pulled from worked-over archives, but these days I find more inspiration from figures off the beaten path.

One such figure is Georges Braque, a Frenchman who started a career in house painting, following in the footsteps of his father, before later revolutionizing the art world. Braque is one of the three pillars of the 20th-century art scene. The first, of course, is Picasso; the second Matisse. The third is Georges Braque, who together with Picasso, pioneered Cubism, forever changing our understanding of how an artist can use perspective.

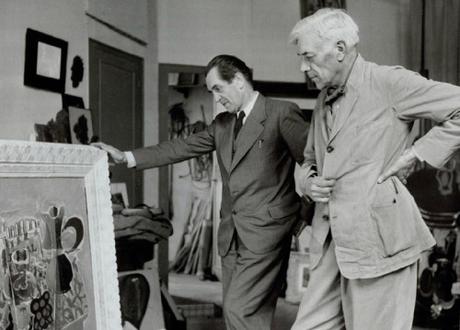

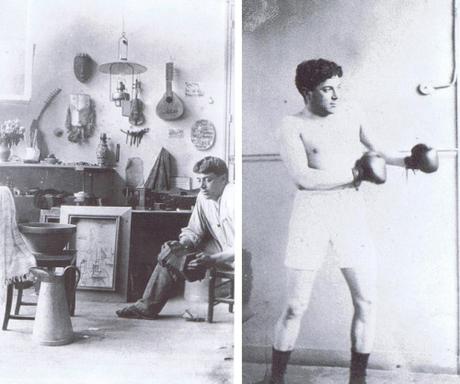

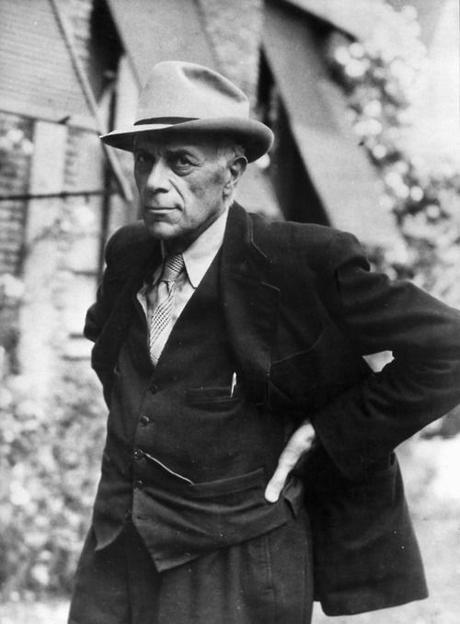

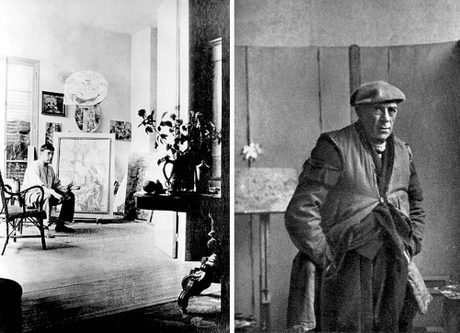

Braque was a fantastic dresser, and while he maintained a strong interest in personal style throughout much of his life, it was really in his later years that he bloomed. You can get a sense of his style through these photos. In the earlier years, he wore matching work suits with preciously tied bows and well kept hats. In the image below, you can see him standing in Picasso’s Boulevard de Clichy studio in 1909, positioned between Paul Cézanne’s “Bathers at Rest” and Picasso’s “Nude with Raised Arms.” Here, Braque is wearing a Kronstadt hat – a big, flat-topped bowler with a curly brim – in homage to his hero Cézanne, who wore the same style. This unusual ensemble wasn’t just for the photo; this is how Braque often dressed at the time.

Braque’s attention to style didn’t go unnoticed. French fashion designer and illustrator Georges Lepape once rhapsodized about Braque’s immaculate sense of dress when they were both at the Académie Humbert:

“How I used to envy Georges Braque – powerful, Olympian, sporting tweed suit, flannel shirt with detachable collar cut extremely low, brilliant white, stiff. His tie is black silk, one centimeter wide, tied in a tight bow. Mahogany leather shoes with thick soles, black bowler hat, and a little Javanese bamboo cane, thin and flexible … that I rediscovered fifteen years later, in the first appearance of Charlie Chaplin on the cinema screen.”

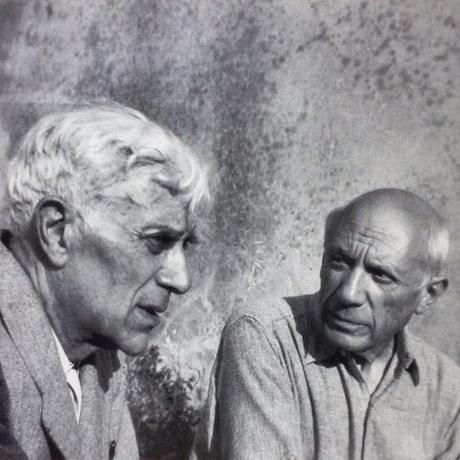

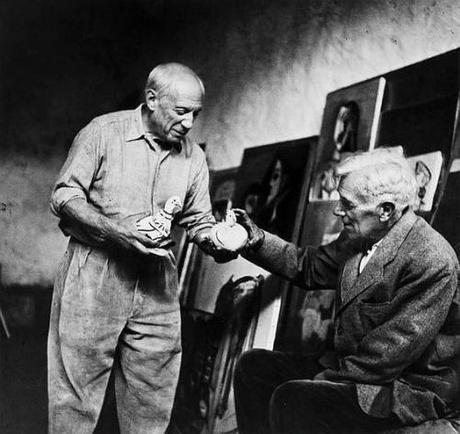

This was during Braque’s early years, before the photo above was taken. Braque only met Picasso after he graduated from university. The two naturally used art as a way to relate to each other, but also found common ground through clothing. Once, Braque picked up an auction lot of a hundred hats at a public sale, then gifted Picasso some of the bell-shaped cloche styles for novelty sake (Andre Salmon described them as “the envy of Second Empire bookmakers”). Despite the hats looking ridiculous, Picasso had great fun wearing them one summer when he was in Céret. “What a surprise, you have no idea how much I laughed, especially in the nude,” he told Braque. “With Manolo, we put them on last night to go to the café, but with false mustaches and sideburns applied with cork.” Later, he asked Braque to pick him one of those bright blue suits he often saw the artist wear. They were called “Singapores” at the time, but confusingly favored in Western Europe for their American style.

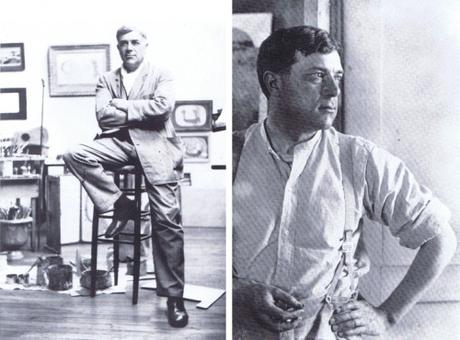

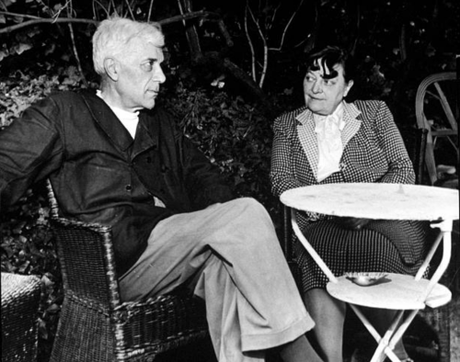

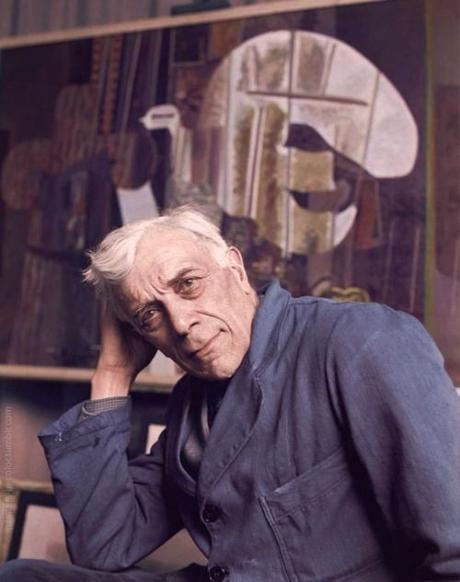

Like for many people, Braque’s sense of dress naturally evolved over the years, becoming subtler and relying more on nuances. Still, change came slowly and gradually. German art historian and dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who traded heavily in French art, considered Braque to be something of a discrete dandy. “He’s still extraordinarily elegant. In those days he used to wear very simple blue suits, of a wholly distinctive cut, the like of which I’ve never seen. He also had black shoes with square tips but not huge soles, which he said came from Abbeville. Like Max Jacob, he had a black ribbon tie. He looked really stylish in all that.”

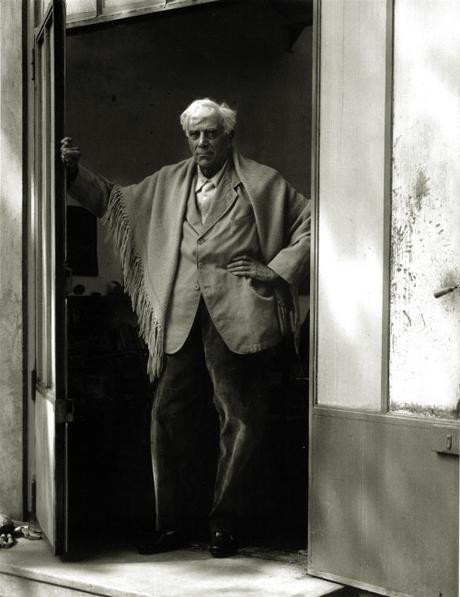

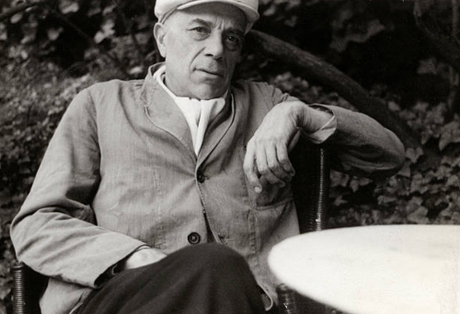

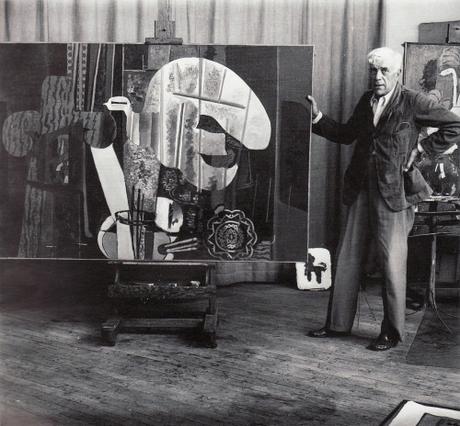

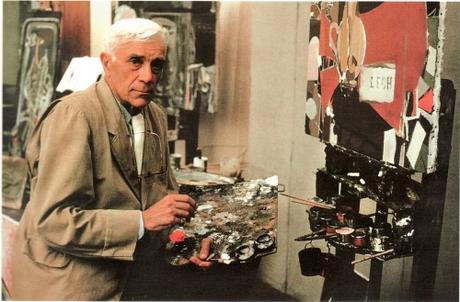

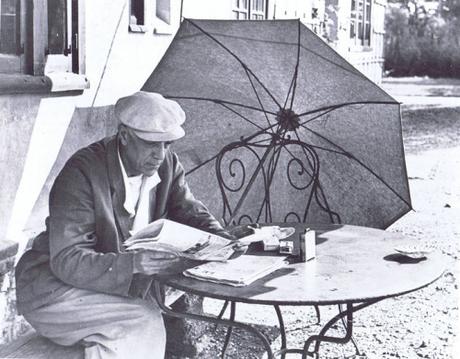

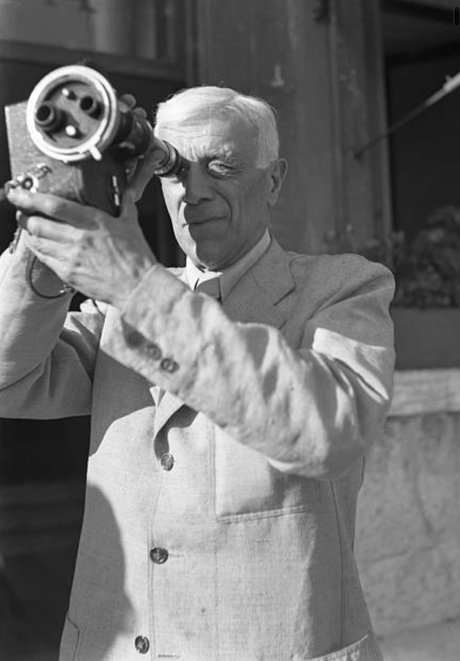

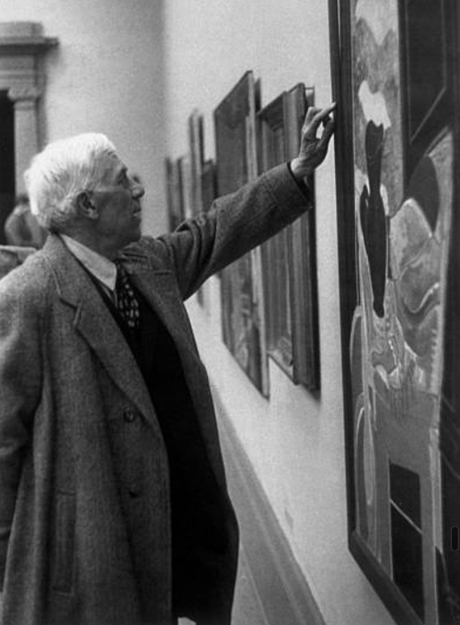

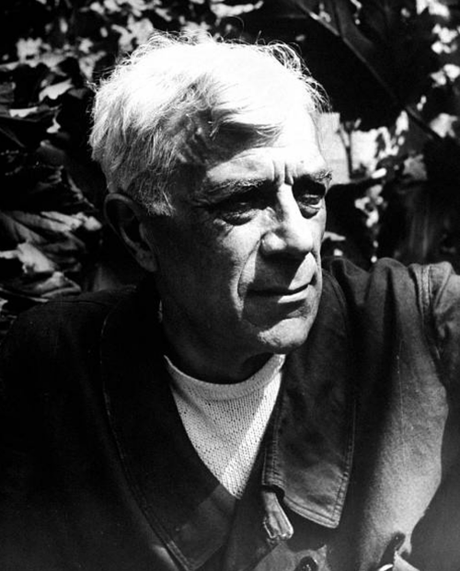

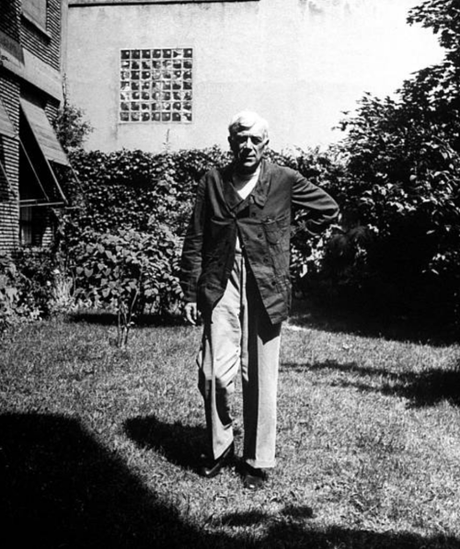

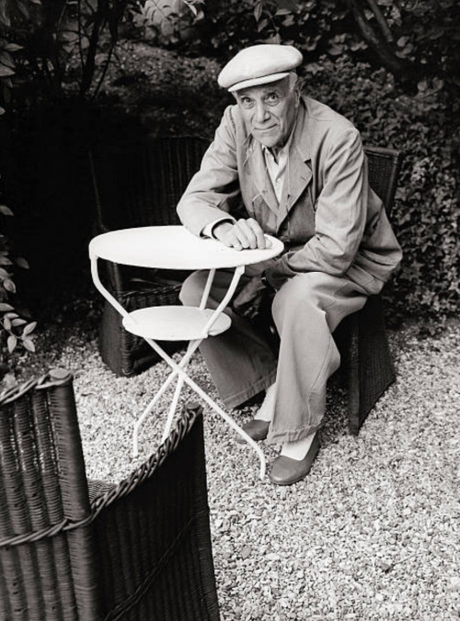

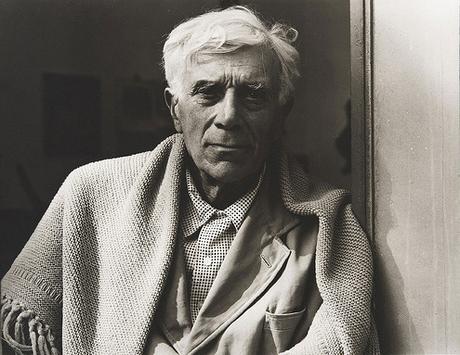

The best of Braque’s style can be seen in his later years, when he was a more mature man and his wardrobe transcended both fashion and tradition. For walking around the promenade or beachcombing, Braque favored a crumply corduroy suit, which he would set off with a tartan tie, yellow wool or silk cravat, and/ or headgear appropriate for the season – straw for summer, wool for winter (he always loved hats, and seemingly had one for every occasion).

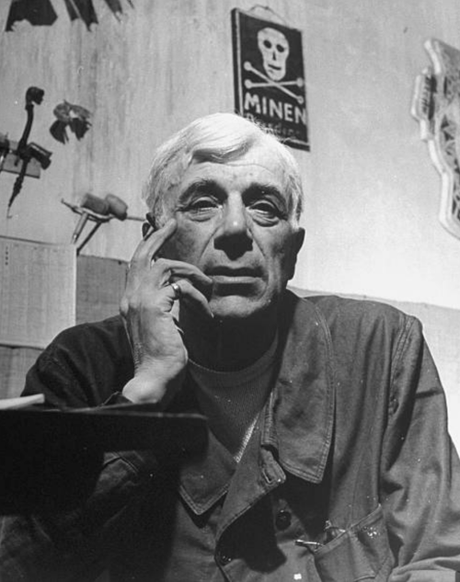

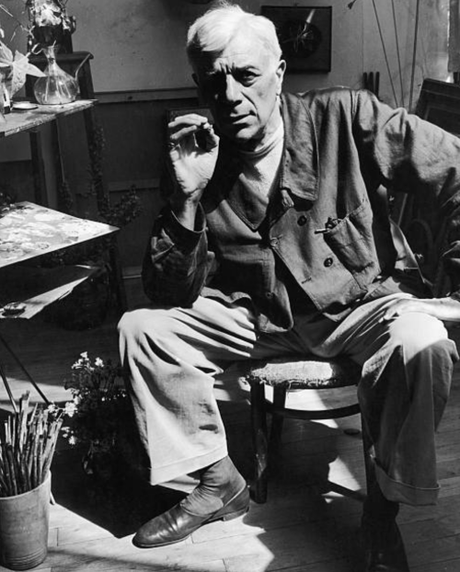

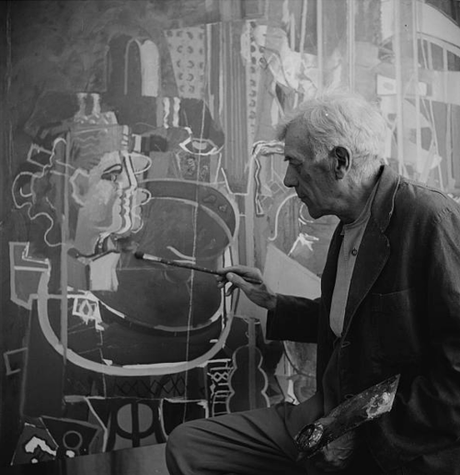

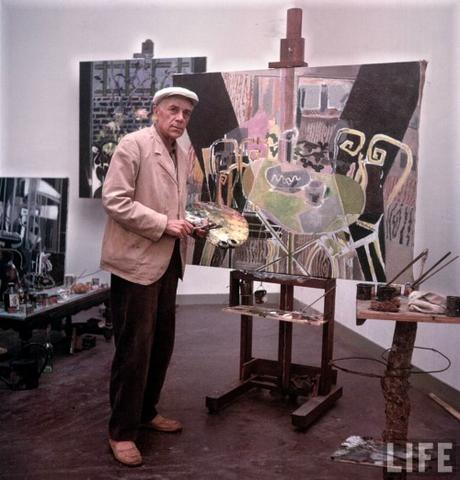

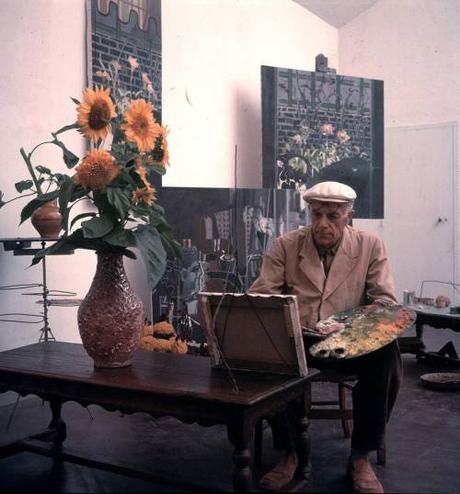

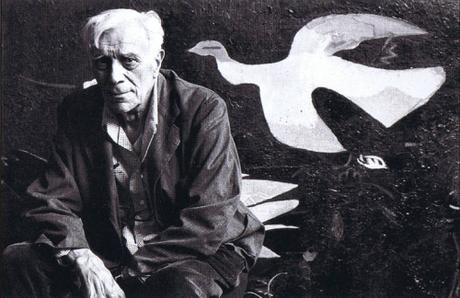

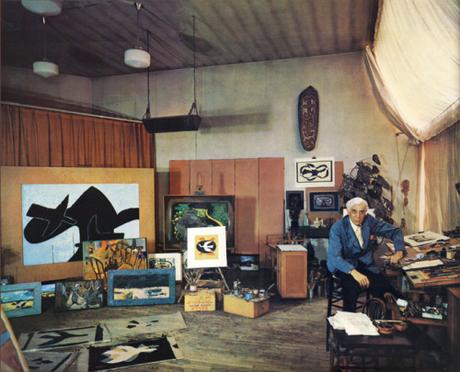

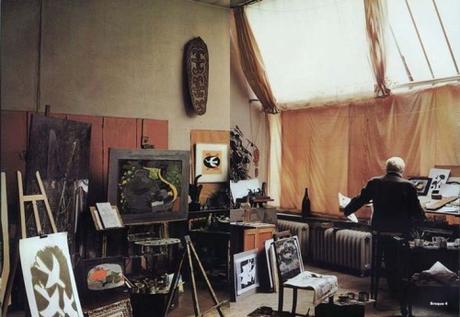

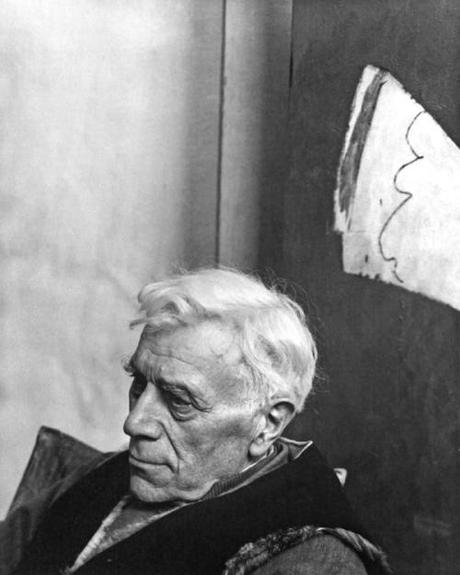

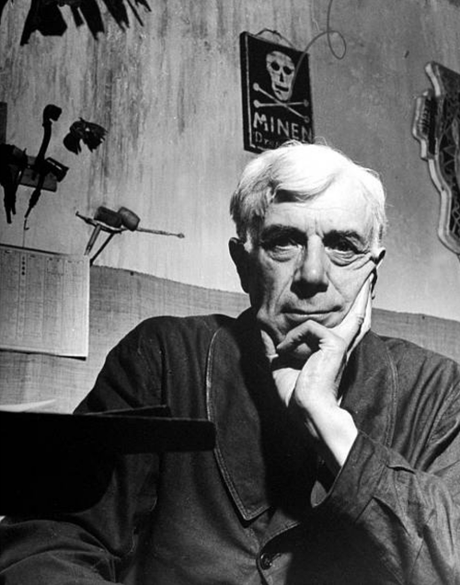

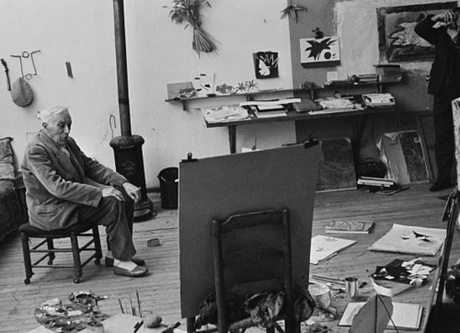

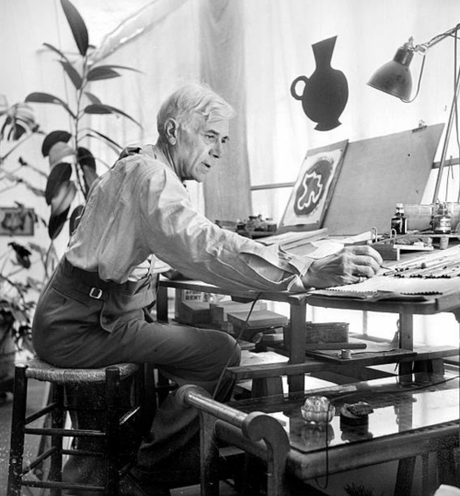

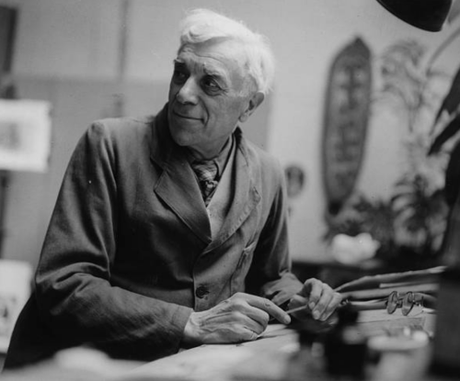

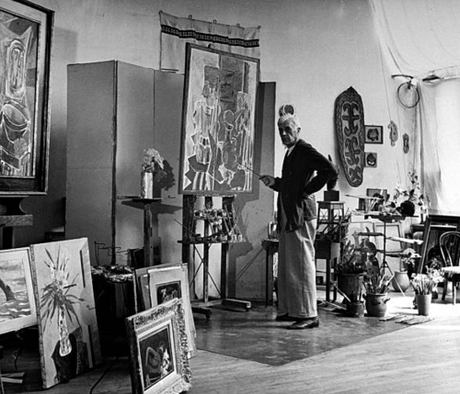

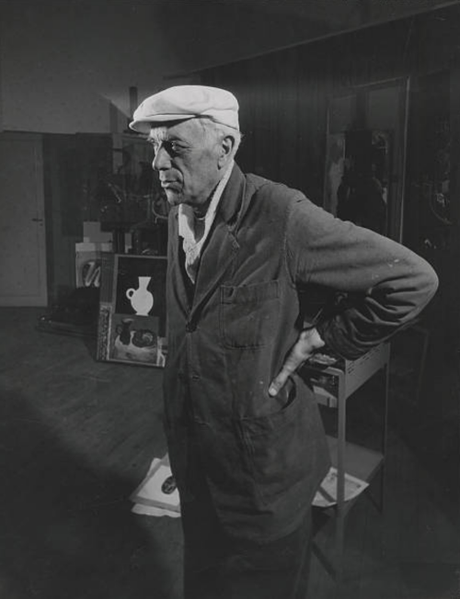

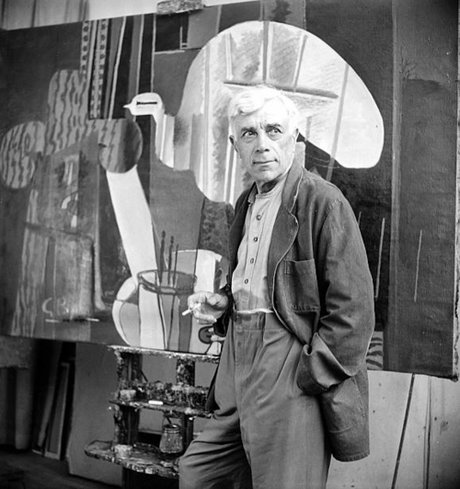

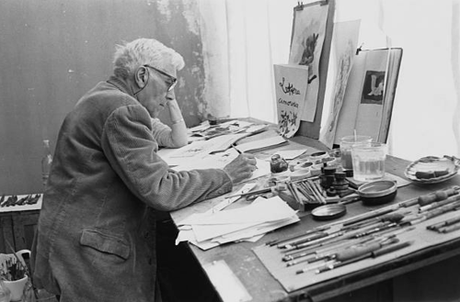

When he was at home or in his studio, however, Braque wore blue cotton tunics, corduroy trousers, and soft soled, leather slip-ons. Photographer Robert Doisneau described Braque as always being in his “carpet slippers, with his lordy ways.” One winter, Brassaï once found the French artist in his atelier wearing an extraordinary fur-lined jacket and a dashing wool cap covering his white mane. Braque had a certain sensibility about him, something of a detached hero, quiet and solitary, which in many ways reflected in his sense of dress. French writer Henri-Pierre Roché even thought Gary Cooper modeled himself after the painter.

In photos, Braque’s style can look accidental – more a creation of the photographer behind the camera, rather than the subject. However, Braque’s sense of dress was always deeply considered. In his book about the artist, Alex Danchev wrote that Braque loathed the traditional white painter smocks favored by his contemporaries, such as Matisse and Rouault. “I hate those smocks,” he told Brassaï, “because they’re too confining. I much prefer mechanics’ overalls.”

It’s hard to draw style lessons from Braque since everything is so particular. That said, you can see him easing into his clothes over the years, with combinations feeling ever more stylish and natural. For me, that’s what breaking the rules is all about. You dress by them until they become second nature, and then you find your own path. For Braque, that meant combining French workwear with British materials, but also adding a bit of comfort with his soft, leather slip-ons. Things were built for purpose, but looked great because they had a real sense of character – both inherent to the object and reflecting that of the wearer. Braque treated clothes the way he treated almost everything. An excerpt, to end, from Danchev’s chapter on the artist’s home:

“[Braque] was back the following summer, renting first in Dieppe, and then Varengeville. In 1930 he bought a plot of land and asked Nelson to build him a house. Nelson felt very proud. Pride soon turned into anxiety. Like Perret before him, Nelson discovered that Braque had an idea of his own about building. The right construction was as important as the right clothes. The architect had imagined a wall of glass bricks as a shield against the west wind. This conception was uncompromisingly rejected. ‘No, that is Nelson’s house. What is wanted is Braque’s house, a house that I can master.’ Braque had firm views on glass in general. ‘Above all, I don’t want top-quality glass! None of those panes that are too clear and too perfect. When I open the window, I want to see nature in a different way, and differently again when I go out.’ What was wanted, it transpired, was a Norman peasant’s hut, long, low-slung, snug under the eaves, custom for le patron. That was what he got.”