Last month, in The New York Times, Kelsey Francis published a heart-wrenching account of her experience giving birth to her stillborn daughter, June. June was supposed to arrive on Christmas Day back in 2010. At the time, Francis’ three-and-a-half-year-old son was so excited about the prospect of becoming a big brother on Christmas morning that he built a “diaper train” in the middle of the family’s living room by laying shrink-wrapped packages of Pampers and Huggies in a row. “Can we name the new baby Peanut Jesus?” he often asked.

About a month before her expected delivery, however, Francis stopped feeling the kicking, rolling, and jabbing that typically happened in her womb. Her husband drove them to the emergency room where, on a grainy ultrasound screen, she saw the lack of movement and failed to hear a heartbeat. The following morning, the nurses rushed Francis to a small corner room in the labor and delivery floor so she could be induced. This was where she first heard the word “stillbirth.”

“Outside my hospital window, I could see an elementary school playground,” she recounted. “Children bundled in bright winter coats and hats poured out of the school doors for recess. Faint laughter and screams floated up four floors and permeated the brick exterior of my room. I wanted those children to go away but also to never stop.” Francis gave birth to June that morning in the silence of her blue-labeled room with the florescent lights hovering overhead. The six-pound-ten-ounce baby girl was laid on Francis’ chest. “Lovely and perfect and absolutely still. Cherubic lips and long eyelashes. Tiny wisps of eyebrows. I didn’t know love and grief could be born at the same time, but in a single moment, my heart grew exponentially and shattered.”

When she and her husband came home from the hospital, her son was filled with pressing questions. “Why did the baby die?” “When is June coming home?” Trying to keep the conversation honest and age-appropriate, Francis explained to her three-and-a-half-year-old that he would not be getting a sister on Christmas morning and, no, she can’t grow another one in time. One night, shortly after burying her daughter — and, oddly, buying another cemetery plot for her and husband to share (the cemetery was having a sale) — her son asked about June again while being put to bed.

“I had no words left. Instead, I crawled in next to him, inhaled the lavender scent of his hair and let him do the talking. He talked about getting a toy cement truck for Christmas, seeing his cousins, and the giant glass of eggnog his grandmother had let him drink at her house. Then he said: ‘Mommy, you said it’s hard to understand what happened to June, but I want it to be soft. Soft. I released a deep sigh. ‘I know. I want it to be soft, too.’ Softness is exactly what I needed. It’s what our whole family needed. Overnight, everything in our lives had become increasingly harder to understand. Except the little boy lying next to me. His words and needs were clear. And they were soft.”

Francis’ story is one of those terrors few people dare to imagine. It continued to replay itself over and over again as she and her husband revisited June’s gravesite, shoveling snow when necessary to keep the area tidy. (The one beam of light is that Francis gave birth to a healthy daughter a year later). But her account made me think of the emotional meaning of textiles — cotton, flannel, lace, silk, wool, linen, and tulle. Francis’ son’s request, “I want it to be soft,” is one of those things that should be familiar to anyone who has ever needed to feel the physical and emotional comfort created by the touch of soft textiles on the skin.

Our emotional associations with touch are arguably innate and perhaps even universal. In an article published in Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, Hilary Davidson examines the fabrics people are buried in. What is the last thing someone ever wears, and who decides what emotions those garments embody? For her study, Davidson analyzed excavation findings from British cemetery sites, where the bodies of poor mid-19th century Londoners were often laid to rest. “The choice of interred textiles and garments — such as a satin baby’s bonnet, pinned silk ribbons, and a false waistcoat— their qualities and construction all bespeak emotions around pride, dignity, religious feeling, tenderness, and socially codified grief,” she writes. “Clothing fragments become a substitute fleshliness as the bodily tissue they cover wears away, the last traces of the invested, materialized emotions surrounding death.” The softness of some of those garments was also presumably meant to bring the dead some eternal comfort.

Such associations between touch and emotion mostly follow a predictable pattern. We like things that are soft, silky, and smooth; we dislike things that are sharp, cold, and jagged. There’s a reason why challenging days are described as “hard” and “rough,” while sweet moments make you feel “warm and fuzzy.” One study published in Acta Psychologica found a relationship between body temperature and feelings of exclusion. When people feel socially excluded, the mere act of holding a warm beverage can make them feel better.

Similarly, in a series of psychological experiments, University of Michigan professor Joshua Ackerman found our thinking can be affected by the physical things we handle. “These influences are not trivial – they can sway how people react in important ways, including how much money they part with, how cooperative they are with strangers, or how they judge an interview candidate,” Ed Yong wrote of the study in Discover. “Weight is linked to importance, so that people carrying heavy objects deem interview candidates as more serious and social problems as more pressing. Texture is linked to difficulty and harshness. Touching rough sandpaper makes social interactions seem more adversarial, while smooth wood makes them seem friendlier. Finally, hardness is associated with rigidity and stability. When sitting on a hard chair, negotiators take tougher stances, but if they sit on a soft one instead, they become more flexible.”

In rare cases, these associations can take unexpected turns. V.S. Ramachandran, a behavioral neuroscientist at UC San Diego, along with his grad student at the time, David Brang, now an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan, once published a paper on tactile-emotion synesthesia. Two women in the study, who were simply coded as AW and HS, described having unusually strong and idiosyncratic emotions springing from touching certain materials. “Certain types of textures evoke raw or primal emotions such as joy or disgust,” the authors wrote, “whereas others generate subtle nuances of emotion such as jealousy or guilt.” An excerpt from their study:

In the case of subject AW, the most extreme sensations arise from the texture of denim, causing feelings of depression and disgust, and silk, generating the experience of perfect happiness and contentment. With subject HS, the most acute sensation is gained from soft leather, which she personally describes as “making my spine crawl.” The intensity and quality of each emotion experienced is consistent over time for any given texture (e.g., denim always causes extreme disgust). In both subjects, some textures elicit no sensation (human skin or paper).

One of the tables in the paper lists some of these idiosyncratic associations. Corduroy made HS feel disappointed, fleece drew disgust, rayon was comforting, silk filled her with laughter, soft leather scared her, and textured gloves made her oscillate between feelings of creepiness and excitement. Interestingly, these fabrics induced certain emotions depending on where they were placed on the body. Against the face, a subject may feel one way, but when touching the same fabric with their hands, they felt something else.

Researchers still aren’t sure what brings on these associations. Ramachandran supposes it may have something to do with having connections somewhere in the brain. “In the brain of the fetus, everything is connected to everything. And there are genes which then prune these connections, sculpt the modular organization of the adult brain, so they remove the excessive connections,” he explains. If these genes are expressed in unusual ways, they can leave stronger-than-normal connections.

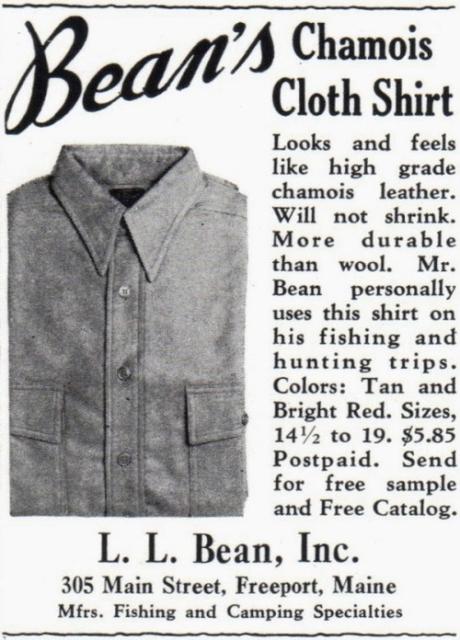

A few weeks ago, I was thinking about the emotional meaning of softness as I put on my LL Bean chamois shirt. In its original form, chamois refers to a very soft leather, often made from the fleshy, inner side of split sheepskin. If you’ve ever washed a car, you’re probably familiar with the material. In clothes, however, there’s also a brushed cotton shirt fabric that goes by the same name – called so because it’s made to imitate the weight and feel of the fleshy variety. If you’ve never felt it before, the texture is a bit difficult to explain. It’s not enough to say it’s soft, although it is. It’s also not enough to compare it to other napped materials, such as moleskin, velvet, or buckskin.

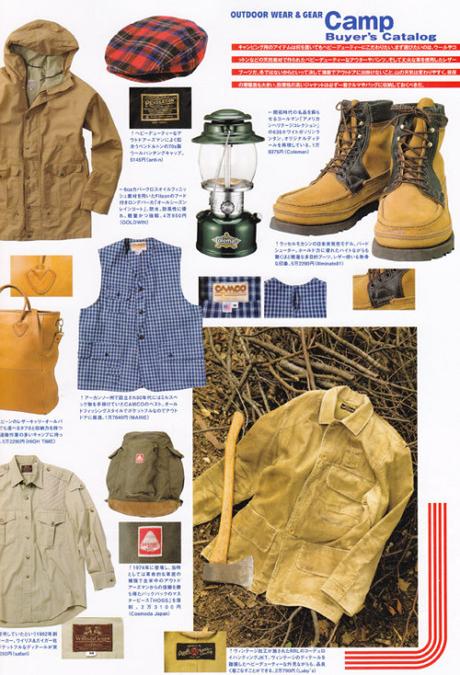

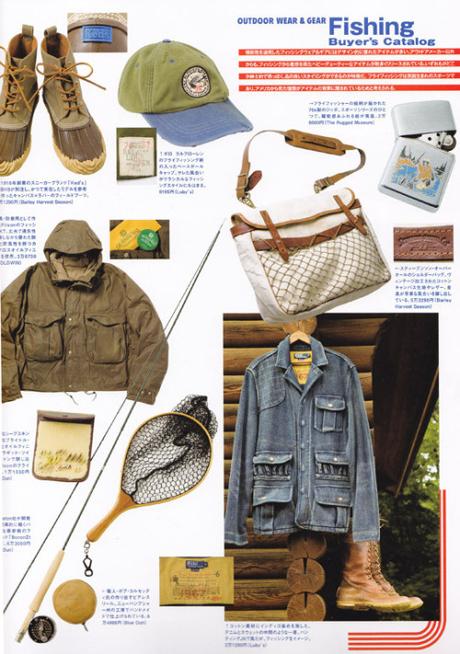

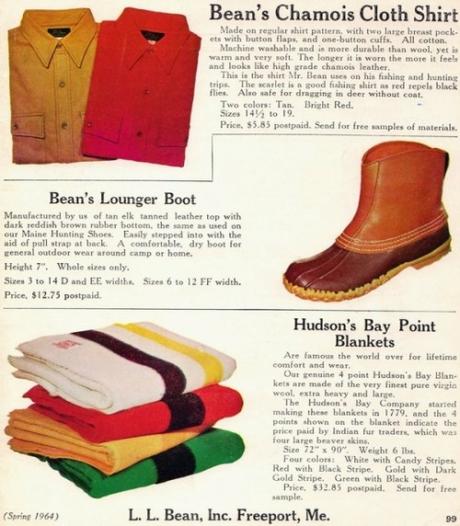

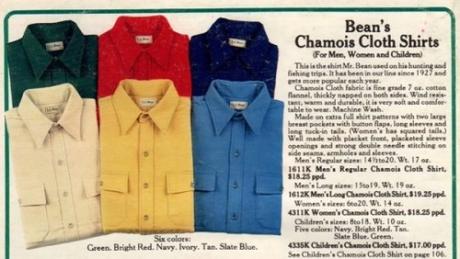

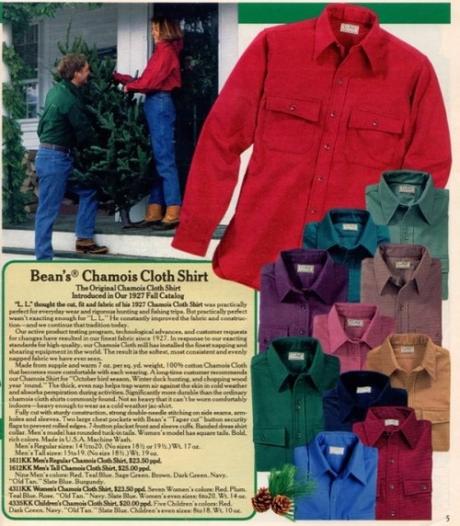

When you first put it on, a chamois shirt will feel cold against the skin. It tingles for about a second or two, then warms up and starts to feel velvety soft — almost like the woolen-covered surface of a billiard table. LL Bean came up with one of the first chamois shirts in 1927. Marketed as a “leatherette shirt,” it was a favorite of sportsmen across America. “The scarlet is a good fishing shirt as red repels black flies. Also safe for dragging in deer without a coat,” a 1960s catalog read. Over the next fifty years later, the company has manufactured the shirt in every color imaginable — barley, ivory, buff-yellow, sage green, loden heather, slate blue, and my favorite, deep black. Supposedly, the slanted flaps covering the chest pockets were made so Mr. Leon Leonwood Bean could more easily hook fishing flies on the outermost corners. Today, they’re just an identifiable style signature for the brand.

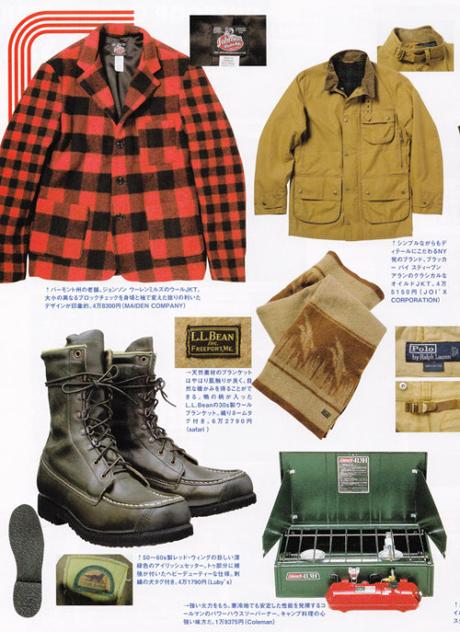

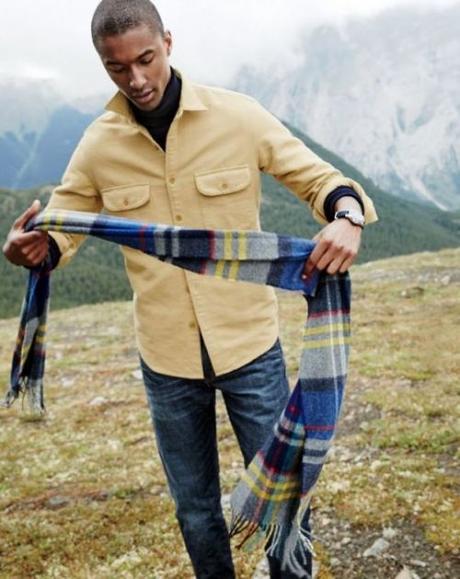

Brian Davis, the co-founder of Wooden Sleepers, says he prefers the vintage chamois shirts from LL Bean and Woolrich. “Vintage ones have faded to a muted, soft color that can only be achieved through years of wash and wear,” he says. “My favorite colors are faded purple, teal, berry, and this soft yellow that is pretty common. I usually wear them like a lightweight jacket, open and over an OCBD or even a hoodie for a more rugged look. When it gets really cold, I’ll wear them over a wool henley and then layer a fisherman sweater over it. This is a real Northeast winter look – functional, but still put together.” He sells them out of his Red Hook, Brooklyn boutique for about $75 per shirt, although readers outside of the area can email him for a remote order.

I love chamois shirts because they’re more than just comfortable — they’re calming. They feel cozy like you’ve never left your bed in the morning. The material is soft, thick, and gives you the same reassuring feeling as wrapping a blanket around your shoulders. Every physical movement brushes the fabric against your skin, making you feel relaxed. Most of all, I love how the outdoorsy shirt naturally layers under the hard exterior of workwear — leather jackets, denim truckers, French chore coats, and the like. It’s as though you lined the underside of a protective shell with a soft layer of brushed felt.

My favorite chamois shirts are from LL Bean’s Signature line, which fits slimmer than the company’s mainline offering. The black version goes well with outerwear in almost any color. The shirt buttons are a little larger than average, which makes them easier to fasten, and the chest flaps slant towards the shoulder joints. Most of all, I like how the 7.5 oz fabric works as a shirt jacket, but can still be comfortably tucked into pants.

Alternatively, if you prefer thicker fabric and smaller buttons, J. Crew’s heavyweight chamois shirts are an exceptional value at $100 or so (often discounted to $70ish on sale). Their new sizing comes in classic and slim, although I find the classic range to be slim enough. I have one of those shirts in cream, which I find to be just as versatile as black. Taylor Stitch’s Yosemite shirt is similarly hefty and comes with visually pleasing, rounded pockets. My friend Pete recently wrote of them: “Their wash-n-wearability means you can fill your closet with these hard-wearing shirts and run ’em to the ground. Nowadays, I prefer the heavier and more modern cut of the Taylor Stitch Yosemite shirt, which I wear everywhere from the jobsite to the campsite.”

There are other notable heritage and heritage-style brands. Woolrich, Filson, Lands’ End, Bill’s Khakis, Duluth Trading, and The Vermont Country Store all offer their versions. I’ve been eyeing the plain beige one this season from Five Brothers, but beware that the Japanese version of the USA label runs short. Proper Cloth and Portuguese Flannel are the ones you need if you want something refined enough to wear under tailored clothing. The fabric is a little thinner, which makes them easier to tuck, and they’re available without the sporty flapped pockets. I don’t want to make too much of it, but a soft chamois shirt one of the most comfortable – and comforting – things you can wear in the fall and winter months.

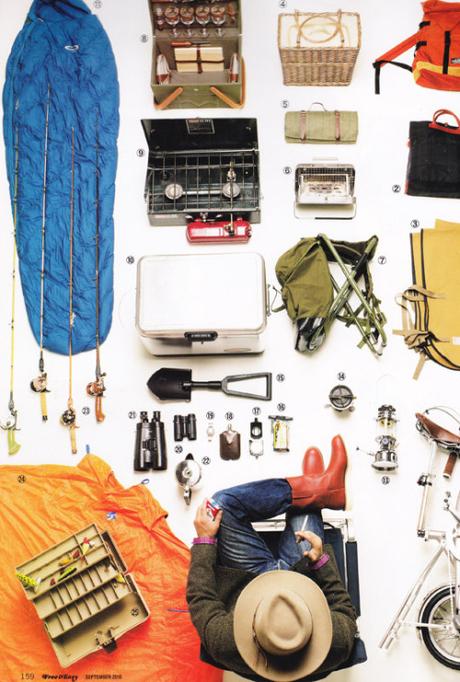

Pictured below: some chamois shirts and the things I think look good with them.