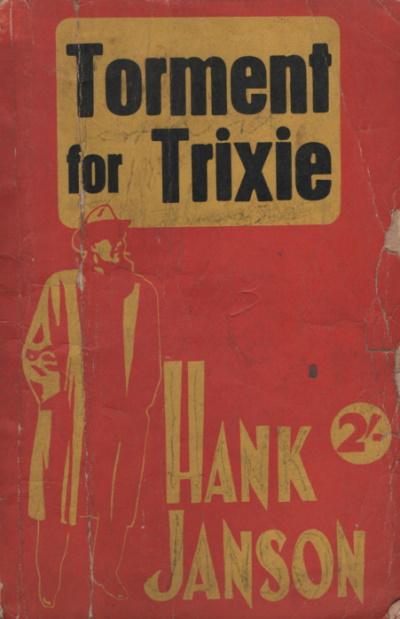

Cover of the first edition.

Cover of the first edition.

Book review by George S.: Torment for Trixie is the seventeenth of the over two hundred novels published under the name of Hank Janson, and in this one the detective hero (also called Hank Janson) is on his best behavior. . What makes the novel quite interesting is that it was written when local police forces were routinely confiscating stocks of Janson novels as obscene. This book’s plot centres on the publicationof a book considered shocking and immoral, and it can be read as a commentary on conventional views of obscenity.

This book belongs to the second series of Janson novels, in which the hero (also called Hank Janson) is no longer a wandering crime-fighter, but now has a job as the ace crime reporter on a Chicago tabloid newspaper. He is a busy man. When his editor criticises his work ethic, he protests:

I’m pulling my weight. You know it. Four days ago I covered the aeroplane murder. Ten days ago I got an exclusive on the mine disaster and was nearly entombed with the second cave-in. Just a fortnight ago I got an exclusive on drugging racehorses.

In this book, he is given what seems a lightweight assignment. A novel, The Inconstant Lover by Jane Grey, is making a sensation as ‘hot stuff’; the author is apparently a female, but ‘Jane Grey’ is apparently a nom-de-plume. Janson is given the task of finding the story behind the book.

He visits the publishers, and by chance is there when a ‘Miss Howard’ arrives.

Her face and hair alone classed her as the school-marm type. Her clothes gave the final touch to the picture. She wore a gray tweed skirt and jacket, a white blouse that fitted up tight around the neck and thick lisle stockings. She’d as much shape as the top of an ironing board.

Janson deduces that this unlikely pornographer is Jane Grey, and persuades her to talk to him.

What happens next is broad comedy, and not all that psychologically convincing. Knowing nothing about alcoholic drinks, ‘Miss Howard’, pretending to be much more sophisticated than she is, downs several cocktails very fast and becomes drunk and incapable. Janson takes her home to his flat, where she stumbles into a full bath and passes out.

To prevent her from catching a chill, Janson undresses her, in a comic parody of the conventional sultry striptease.

She had a lovely face, but her soaked and heavy clothing gave her body the awkward lumpy appearance of a sack of potatoes with a cord tied round the middle.

The skirt was easy to get off. It had buttons down the side and I pulled it down around her ankles. Then I undid buttons all the way down her back and took off her blouse. And if anybody thinks I was getting a kick outa this they have another guess coming.

Janson behaves like a gentleman, and does not take advantage of her, even though he discovers that beneath her school-marm’s clothing she is indeed beautiful; making the point that this is a hero with values. (At one point earlier , by the way, ‘Miss Howard had removed her glasses, and Janson had told her she was beautiful. This is not a novel that ever allows a chance for a cliché pass by.). He follows ‘Miss Howard’ to her home town, Little Falls, a puritanical place where the ladies of the Church Literary Group are indignant about the scandalous book, but do not realize that a local young woman is the author.

So far so comic; the tone is more of screwball comedy than hard-boiled thriller.

The next day, however, the plot thickens. The publishing company have paid Jane Grey, alias Miss Howard, alias Trixy – with a forged hundred-dollar note. What’s more, they kidnap her when she tries rather clumsily to investigate. Now the book turns into a more conventional thriller.

Janson gets on the case and pursues, but soon he too is a prisoner of the forgery gang, who are being financed by a foreign power in order to destabilise the American currency..

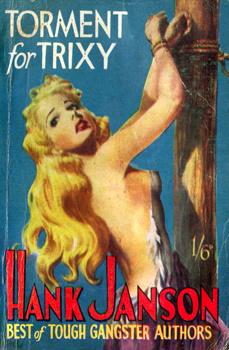

It becomes only marginally more pornographic. There is some torture. Trixie is lashed with a belt – which gives the excuse for the cover picture. Later, Janson is threatened with being deported to some foreign hell, where he will be kept as a slave in a punitive labor camp: ‘The work in the mines is very strenuous. Sixteen hours a day. But I think, with luck, you might live six months or even a year.’

The villain adds,leeringly: ‘There are other establishments that could absorb Miss Howard. Establishments, naturally, of a different nature. [….] As you probably know, such establishments do try to cater for all kinds of tastes. Even for those men who prefer to take their pleasure by force.’

It’s not really a spoiler to tell you that Janson and Trixy manage to escape from these fates, and that by the end she is completely in love with him. The final chapter has them heading for bed together, but nothing is explicit.

The book is fast-moving and fun to read. The plot does not stand much scrutiny, and the villains combine, as so often in thrillers, utter malevolence with extreme incompetence. Despite a few rather leering sentences, the text of the book is by no means as sexy as its cover.

What makes this novel quite interesting, though, is that it deals with the topic of ‘hot’ literature, It was written just after the trial that sent two of Hank Janson’s publishers to prison for two years, and can be read as a commentary on the case.

I like his comment on the Church Literary Group:

That’s the kinda thing that happens in small towns, The book had gone over big in Chicago and New York. Smaller communities, outside the bigger towns seized upon the book as an example of the decadence of life in the big towns. It was really a kinda justification of their own existence.

(The prosecution of Janson novels happened mostly in the smaller Northern towns, where the Nonconformist churches were powerful.)

The chairwoman of the Literary Group reads excerpts from the novel, especially its infamous page 256. Listening, Janson notes: ‘It didn’t seem very terrible to me. Maybe I’m broader-minded than most people.’ the passage had shown a man and girl swimming together. She hit her head on a rock, and, in Janson’s paraphrase

So the fella saves her life, lugs her outta the water, and since there’s no doctor within miles, patches up her head the best way he can, strips off her costume, driews her down and pops her into bed so she won’t catch cold.

Janson asks the ladies why this passage is thought so terrible, and the Chairman replies.

The Chairman said indignantly, ‘Young man. You must know very little of life. Surely the inference alone is sufficient. This girl was with this man. He tore away her clothes, and who can doubt that in the same moment he stripped her of her self-respect.’ She tilted her chin high and stared around her.

For the puritanical Chairman ‘They spent the night together in that shack. Surely that is inference enough.’

Like the prosecuting counsel in the 1952 trial, she is reading into the book what it does not state. Janson tells her:

There’s nothing wrong with the book. The only thing wrong is the way you folks look at it. You’ve got a suburban attitude. You see rottenness where no rottenness exists. This book isn’t obscene. It’s like life, maybe with a little extra flavouring. The only vice and obscenity in the book is what your own evil minds read into it.

Trixy, the author of the ‘hot’ novel, is shown an innocent. Is that how Stephen Frances, the author of these first Janson books, saw his work? His upbringing had been tough, and not at all sheltered. In his pastiches of American crime thrillers, he did not pretend that the world was kind, or that sex did not exist. He had a real talent for narrative, lacked much literary sophistication, and was probably naïve when it came to the standard rules about what was allowed and what was not allowed in fiction. He presented ‘ life, maybe with a little extra flavouring’, and the sales figures showed that other people responded to what he wrote.

Critics will doubtless object to the presentation of female characters, very much subject to the ‘male gaze’ and judged on their appearance. Janson could maybe claim, though, that his presentation of women is more rounded than that of the Chairman and her puritanical associates (and Mervyn Griffith-Jones, the prosecutor in the Janson court case, as in the later Chatterley trial). They see women simply as victims of disgusting males. The subtext of this book is the development of Trixy from naïve young woman, who presents her simple erotic imaginings in a novel, not realising that others will find them disgusting, into a liberated young woman, no longer restricted by ugly tweed clothing, who is in charge of her own sexuality when she invites Janson into her bed. Yes, that’s something of a male fantasy, too – but with a book like this, what do you expect?

P.S. Thanks to Val Hewson, who has pointed out that both the drunk scene and the meeting of the literary group are closely based on scenes in the film Theodora Goes Wild (1936), an excellent screwball comedy starring Irene Dunne and Melvyn Douglas. So closely based that you could call it plagiarism (or if you’re moder, hommage)

P.P.S My copy is a later edition, published when Janson and his publishers were trying to avid police raids, so it does not have the splendidly lurid first edition cover printed at the top of this post, but this much drearier design: