Unfortunately, it ain’t this simple (from doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.008)

Certain research trends in any field are inevitable, because once a seductive can of research-question worms is opened, it’s difficult to resist the temptation to start hooking in. Of course, I’m not against popular trends in research per se if they lead to a productive, empirical evaluation of the complexities involved, but it can sometimes result in a lot of wasted time. For example, in conservation ecology we’ve had to suffer 15 years of wasted effort on disproving neutral theory, we’ve bashed heads unnecessarily regarding the infamous SLOSS (‘Single Large Or Several Small’ reserves) debates of the 1970s and 1980s, and we’ve pilfered precious years arguing about whether density feedback actually exists (answer: it does).

The latest populist research trend in conservation seems to be the ‘land sparing versus land sharing’ debate, which, I (and others) argue, is largely an overly simplistic waste of time, money and intellectual advancement to the detriment of both biodiversity and human well-being.

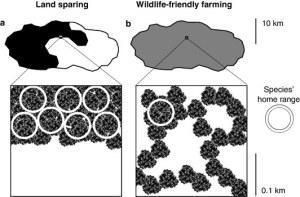

Land sparing is generally used in reference to agricultural practices (although in theory, it could apply to any human endeavour where native vegetation cover is required to be removed or degraded, such as for electricity production) that are purposely made to be high-yielding so that they require the smallest amount of land. At the other extreme (and the ‘two extremes’ of a continuum concept is half the bloody problem here), land sharing requires a larger land footprint because it relies on lower-yielding, biodiversity-friendly (agricultural) practices. Proponents of land sparing argue that only by amalgamating patches of remnant native vegetation can we avoid massive fragmentation and the pursuant loss of biodiversity, whereas those pushing for land sparing argue that the matrix between the big undeveloped bits must be exploited in a more biodiversity-friendly way to allow species to persist.

As it turns out, they’re both right (but their single-minded, extremist positions are not).

Claire Kremen‘s new (and free) review paper published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences is the first really intelligent overview of this prickly polemic. She demonstrates rather eloquently and exhaustively that it cannot and should not be viewed as a binary choice for land management.

Following well-established conservation principles, it is abundantly clear that the larger the area left untouched by sticky human fingers, the greater the number of species it can hold. Probably one of the best and most extreme examples of ‘land sparing’ has recently been publicised by the amazing biodiversity that has since re-colonised the Chernobyl exclusion zone (i.e., remove people and biodiversity thrives). We also know beyond a shadow of doubt that fragmentation is bad in this regard because it reduces the effective area for species persistence, even though the total area under protection (or left alone) might be large. Just like the pointless SLOSS debate, it’s a no-brainer that land sparing – if it results in larger protected areas of native vegetation — will outperform land sharing. Conversely, and as I myself (and with my great colleagues, of course) have shown, what happens outside reserves can be just as important as what happens within for the fate of biodiversity that reserves are meant to protect. In that case, good ‘matrix’ management (i.e., land sharing) is essential.

So how do you reconcile the two? One of the key issues here that Claire points out very clearly is that just because you intensify agriculture (and increase yields), doesn’t mean that you’ll reduce your total land footprint. In fact, in most cases increased yields and intensification result in even more land being turned over to agriculture (known more generally as the Jevons Paradox), which sort of throws the whole justification for land sparing out the window. Indeed, as long as the global human population continues to increase, we still have to produce more food because of a Red Queen effect (in fairness, most hunger is a distribution, rather than a production problem — if we could allocate all the area currently under production for livestock feed instead to human food production, we could, with appropriate distribution, feed another two billion human beings). In other words, it’s entirely insufficient just to say that you’ll intensify and she’ll be right, you have to allocate, protect, legislate and incentivise to make sure that any spared land is in fact set aside for biodiversity — it is a socio-economic, not biological, issue.

At the same time, we know that just increasing the number and size of protected areas will be insufficient to prevent the worst of the extinctions to come; we also need a fundamental, global shift towards biodiversity-friendly practices in the spaces in between. Enter land sharing. Within these lower-yield patches, some of the most promising advances — in terms of hunger alleviation, yield maximisation and biodiversity enhancement — are coming out of the agroecology sector (systems that are based on promoting favorable ecological interactions within the agroecosystem). As the owner of a small farm applying agroecological approaches, I can certainly get behind that idea.

Claire’s comprehensive paper is a must-read resource for anyone wanting to wade into the land sparing/sharing quagmire. Be warned — your preconceived notions might be unceremoniously trashed (mine were).

CJA Bradshaw