Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, director of the Iranian Ministry of Defense’s research department and architect of the nuclear weapons program, was assassinated on November 27, 2020. According to the Iranian Fars news agency, the assassination took place using a remote-controlled machine gun placed on the platform of a truck that self-destructed immediately after the attack. Iran and U.S. intelligence sources claim Israel was behind the attack, although the possibility has also been raised that the Mujahideen-e-Khalq opposition group carried out the assassination, either alone or in cooperation with foreign operations. In any case, the targeted killing points to shortcomings and a possible leak in Iran’s counter-espionage and security organizations.

The killing of Fakhrizadeh may well be part of Israel’s efforts to prevent Iran from gaining access to nuclear weapons. According to current estimates, in the summer of 2021, Iran would have enough uranium to make two atomic bombs that could be deployed as warheads for Iranian missiles. This assessment represents the timeframe within which either a diplomatic (“window of opportunity”) or armed solution to Iran’s nuclear weapons program should be found.

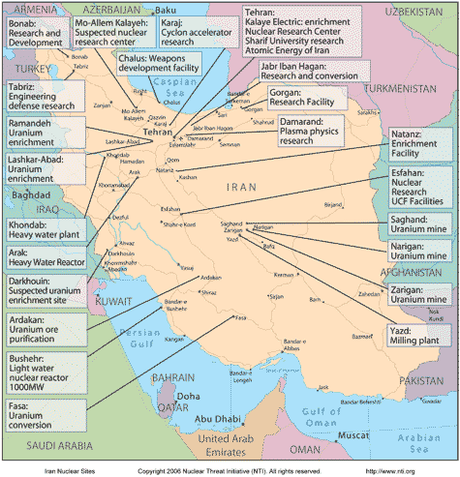

As early as 2008, the CIA knew Fakhrizadeh had sought to build a nuclear warhead for an intercontinental ballistic missile. In addition to the leader of the nuclear weapons program, Fakhrizadeh was also the brigadier general of the Revolutionary Guard. Following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Iranian leadership decided to hide its nuclear weapons program. Fakhrizadeh transferred the bomb development project to Malek Ashtar University of Technology in Tehran and established a defense innovation and research organization, which was relocated to a new location. As early as 2008, he was found to have been involved in Iran’s 111 project (loading a Shihab 3-type missile with a nuclear warhead).

The Iranian leadership also decided to separate the military nuclear program, which would remain confidential and be further developed under Fakhrizadeh, from projects that could be presented as peaceful (including uranium enrichment). The latter projects were under the auspices of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran.

The latest attack is part of Israel’s targeted killing program in Iran and its behind-the-scenes wars elsewhere because, according to Syrian media, a high-ranking officer in the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps was killed at the same time by drone strike in Al Qaim, Syria. operation in Tehran. A decade ago, four Iranian nuclear physicists (Majid Shahriari, 29 November 2010; Dariush Rezaeinejad, 23 July 2011; Masoud Alimohammadi, 12 January 2012; Mostafa Ahmadi Roshan, 11 January 2012) were killed by motorcyclists. Of course, Iran is seeking reciprocal revenge for the assassinations, and last week, for example, three Iranians who had tried to attack the Israeli embassy in Bangkok were released from Thailand as part of a prisoner exchange.

Efforts have been made to halt Iran’s nuclear program on several occasions and often in various ways. The murders of key figures in Iran’s nuclear program are only a small part of this stopping effort. The following is a very limited list of other measures taken to end the nuclear program:

Iran’s nuclear program agreement and sanctions

The JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) is an agreement between Iran and the P5 + 1 group (China, Russia, France, Britain, USA + Germany) negotiated in 2015 on Iran’s nuclear program. The U.S. withdrew from the agreement in 2018 under President Donald Trump but incoming President Joe Biden has expressed a desire to update the agreement on the basis of the Democrats 2020 party program. The key elements of the original agreement were:

• The UN lifts all its sanctions on Iran

• Iran limits uranium refining to 3.67% (nuclear weapons would require 90% uranium), which, however, allows for the peaceful use of nuclear fuel.

• Iran reduces its uranium stockpile from 10 tonnes to 300 kg.

• Iran reduces its centrifuges from 19,000 to 6,104 accelerators.

• Iran converts its nuclear facilities for research and peaceful use.

• IAEA inspectors will have free access to all facilities of Iran’s nuclear program.

Diplomatic influence

In addition to international organizations, Israel has used diplomatic influence, especially in the direction of the United States, to demonstrate the weaknesses of the JCPOA and to verify Iran’s nuclear weapons program as previously dangerous.

In April 2018, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu revealed to the world the existence of Iran’s secret nuclear materials – as evidenced by the 100,000 documents obtained by the Israeli intelligence service from Project Amad from the Iran’s Atomic Archives. The documents contain several details of the scope, extent and intent of Iran’s nuclear weapons development program. Contrary to the allegations made in Iran’s December 2015 report to the International Atomic Energy Agency, it is now known that:

1. Iran has a nuclear weapons development program called Project Amad.

2. An Iranian state-funded and targeted researcher (Mohsen Fakhrizadeh) worked extensively on technology designed to build a nuclear bomb.

Documents show Iran has lied to the IAEA and the world in denying that it has ever carried out nuclear weapons programs. Instead, according to the Israeli view, Iran thus had a clear and rapid path to unrestricted uranium enrichment and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

STUXNET and cyber attacks

STUXNET was a virus program by Mossad that paralyzed Iran’s nuclear program and significantly slowed down the development of nuclear weapons. Cyberspace warfare is more common today; this year, for example, a cyber attack took place on 24-25. April 2020 when Iran struck through U.S. servers on several water and wastewater management and control systems across Israel. Israel, for its part, felt Iran had crossed the “red line” in hitting civil society structures. The counterattack took place on 9 May 2020 as a sophisticated cyber attack on Iran’s largest and most modern port of Shahid Rajaee in Bandar Abbas, resulting in a sudden and unexplained stoppage of the port following the collapse of the entire logistics system.

Sabotage of production facilities

Sabotage of production facilities affects not only Iran but also Lebanon. As the country is just recovering from the August 2020 explosion at Hezbollah’s ammonia depot in the port of Beirut, Beirut precision missile plants made headlines because they pose a risk of new explosions in the middle of a civilian population.

In 2013, the Fordo nuclear power plant in Qom Province, Iran, was seriously damaged. The explosion felt strongly within a three-mile radius around Fordo and “destroyed much of the installation”. After the explosion, Iranian forces quickly besieged the facility and prevented anyone from getting 15 miles closer to it. Iran banned the blast and Israel banned sightings of Israeli fighter jets in the vicinity of the facility before the blast.

There have been a number of unexplained explosions or disruptions in Iran related to the nuclear weapons program in recent years. Some may be damage, human error, or deliberate sabotage, and for some targets, Iran may have rightly blamed Israel. I think it is clear that Israel is using all possible means to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon.

Barrier to missile technology transfers

The blocking of transfers of missile technology from Iran / Syria to Lebanon has been a major cause of Israeli air strikes in Syria and Lebanon. For example, a drone attack on 25 August 2019 at a Hezbollah base in Beirut destroyed a vertical Planetary mixer used in space and missile programs to make the high-quality fuel necessary for precision missiles under development. Even more important than the mixer is probably the destruction of the associated computerized control unit. The operation is expected to slow down Hezbollah’s targeted missile program by up to a year.

The last option

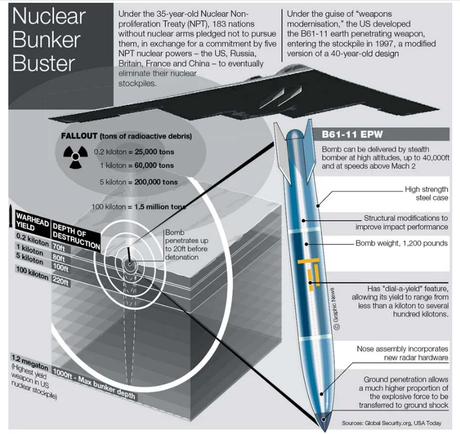

A tool that has not yet been used but has been considered several times has been an air strike on Iran’s key nuclear production facilities. Israel has agreed flight routes for the attacks via both Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan to Iran. However, no strike has been made because the deepest targets in Natanz, for example, are more than 60 meters inside the bedrock and even the most effective “bunker destroyer” missiles can not yet reach them.

Iran’s latest nuclear program facilities are at a depth of nearly 100 meters, destroying them would require a “bunker-destroyer” missile with a nuclear warhead of a megaton, but the destruction has been calculated to be too extensive, with radioactive fallout reaching as far as India. In any case, plans and calculations have been made and updated for this option as well; S-300 system arrival. The Israeli Air Force (IAF) believes it can partially circumvent the threat posed by Iran’s S-300 combat system, for example.

Of course, there is also a zero option, in which case no agreement will be reached with Iran and the program will be slowed down in the current way by various methods. Of course, development is taking place defensively, for example, by refining the Arrow 3 missile, which is designed to combat longer-range ballistic missiles, such as Iran’s Shihab-3 missiles. Similarly, both cyber defense and attack are the core areas of continuous development.

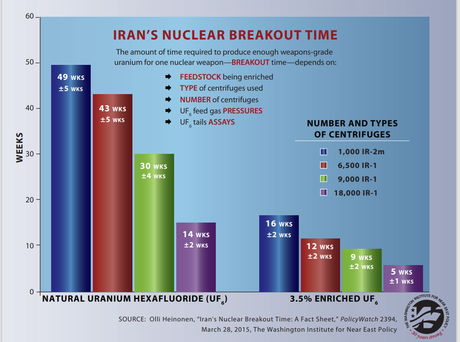

Breakout time window

A key factor in looking at Iran’s nuclear program is a concept called “breakout time,” which is the time required to enrich enough weapons-grade uranium (WGU) to produce at least one nuclear weapon. To produce WGU, uranium must be enriched (eg by centrifuges) to more than 90% of its fissile isotope U-235. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) determines the amount of WGU needed for one weapon at about 27 kg of uranium. Natural uranium contains only 0.7 percent of the U-235 isotope, and approximately 5,000 Separative Work Units (SWUs) are required to enrich it into a single WGU. There are currently about 9,000 operational first-generation IR-1 centrifuges installed in Iran installed at the Natanz and Fordow facilities, and another 9,000 that are not in operation. Iran also has substantial stockpiles of 3.5% enriched uranium hexafluoride (UF6), which can be used as an alternative feed, shrinking the onset period to three months.

Using a 9000 centrifuge with the latest SW-1 model at 1 SWU / year and bringing nearly 9,000 other IR-1s into the network, the time window for Iran’s nuclear program would be about three months with natural uranium feedstock and 4-6 weeks with 3.5% UF6. with the raw material. Iran has also developed a more advanced IR-2m centrifuge rated at 5 SWU / year, and if 1,000 IR-2ms units installed on Natanz were used in conjunction with all 18,000 IR-1s, the corresponding time window would be shortened by a third.

In November 2020, the International Atomic Energy Agency estimated that Iran now owns 12 times more enriched uranium than would have been allowed under the 2015 JCPOA. According to Israeli estimates, Iran, at its current pace of development, would be able to produce enough armed uranium for two nuclear bombs by next summer 2021.

My Conclusions

According to Israeli sources, it is clear that Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was a key player in Iran’s nuclear weapons program in terms of his authority, expertise and organization and is almost impossible to replace. However, neither this nor any of the other Israeli measures mentioned above can completely prevent Iran from carrying out its nuclear weapons program, they only slow those measures; however they show, that no part of those programs is immune to Israeli attempts to block them. There is widespread support in Iran for revenge for Fakhrizadeh’s death, but perhaps not in fear of a stronger Israeli counterattack. In any case, Joe Biden’s work to start negotiations with Iran is likely to become more difficult.

Israeli security agencies have warned as well as prepared for the possibility that Iran might plan revenge attacks against Israeli tourists visiting the United Arab Emirates, among others. It is to be assumed, however, that, once again, it is only a matter of harsh rhetoric for internal use only, or that the attacks will be so modest that there will be no danger of a wider counterattack from either Israel or the United States.

Even if Iran’s retaliation for Fakhrizadeh’s death remained only formal without escalating anything comparable to the war between Iran and Israel, I think it is reasonable to assume that Israel will do its utmost not to allow Iran a nuclear weapon; however, the actions taken so far have only been able to slow down the concretisation of Iran’s nuclear weapon. In this sense, the stakeholders have now timeslot about half a year, a window of opportunity to achieve a diplomatic solution to halt Iran’s nuclear weapons program, the armed settlement could in many ways be very devastating.

Sources e.g: The Washington Institute ,

Earlier about topic:

Iran Nuke Deal Enables The Détente

End Game Approaches on Nuclear Iran

Iran’s nuclear program at the crossroads

The Finnish version of this article first appaered in Ariel – Israelista suomeksi website.