Sometimes it’s good to read a book that does things a little differently and shakes up the reading experience. Scottish writer, Janice Galloway, is an author with an exceptionally dry wit, a poet’s use of words and a tendency to use white space on the page with great innovation. Her first novel, The Trick Is To Keep Breathing, inhabited the inside of a young teacher’s head as she spiralled into breakdown, which might not sound awfully tempting, but is actually so well done and so witty and perceptive that the synopsis is misleading. If you wanted to try her, though, I might suggest beginning with her two volumes of memoir, This Is Not About Me, and All Made Up. They are straight narratives, wonderfully written, about the sort of crazy childhood that is a gift to a talented writer. I wrote a profile of her for Numero Cinq, the new (to me) literary journal I mentioned, if you’d like to know more.

Sometimes it’s good to read a book that does things a little differently and shakes up the reading experience. Scottish writer, Janice Galloway, is an author with an exceptionally dry wit, a poet’s use of words and a tendency to use white space on the page with great innovation. Her first novel, The Trick Is To Keep Breathing, inhabited the inside of a young teacher’s head as she spiralled into breakdown, which might not sound awfully tempting, but is actually so well done and so witty and perceptive that the synopsis is misleading. If you wanted to try her, though, I might suggest beginning with her two volumes of memoir, This Is Not About Me, and All Made Up. They are straight narratives, wonderfully written, about the sort of crazy childhood that is a gift to a talented writer. I wrote a profile of her for Numero Cinq, the new (to me) literary journal I mentioned, if you’d like to know more.

One of Joseph Cornell’s Hotel Andromeda boxes

So this is a novel which, in the simplest of ways possible, starts to play with irreconcilable extremes – what kind of a life has meaning? One in which we turn to the best in humanity, its creativity and art, or one that deals with the worst, its brutality and violence? Is Western civilization an aberration that is bound to revert, over time, to the tyrannies that dominate the rest of the world? How are we even to understand a world that can contain such extremes of beauty and evil? I do love the way that Josipovici writes such lucid, easy stories, based on very natural dialogue, that blossom out into powerful, provocative ideas.

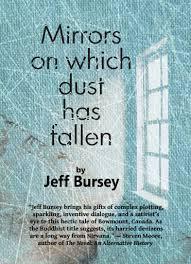

That being said, most of the chapters sink down deep into the characters and their preoccupations. The action arises out of everyday concerns, and yet it also has that edge of satire to it. Whilst a lot of the interest revolves around uncongenial work places, subject to ever more ruthless management directives, there’s also a notable and extensive debate around the place of the Catholic faith at the dog end of the 20th century, fraught as it is in Bowmount with a shameful number of sexual scandals involving children. And equally prominent is the place of art, as explored through a painter creating a very unusual tryptich and a photographer of graphic sexual images. Characters have their fervent opinions, which they impress upon others, and discussions, as they often do in reality, are a mass of interruptions, declarations and exclamations.

The reading experience was, for me, a highly unusual one. Sometimes, I felt like I was looking at swarming bacteria in a petri dish, everything felt so up close and I was so deep into it. I had to put the book down in order to gain sufficient distance to see the relationships of everyone intertwined in this microcosm, to feel the outlines of the story again. There were parts (mostly in bars) where I felt very entangled in the dialogue, but then there were other places when the head-hopping was fluid and lovely, as in a wedding service near the end of the book where we shift between a number of storylines that have been developing over the course of the narrative, each unfolding inside a different character’s head. Which is to say that you are taken through a number of experiences that are oddly akin to the experience of reality, whilst being at the same time clearly artificial and only possible in the realm of storytelling.

I had to look up the title, which seems to come from Bahá’í teaching and talks of children as being mirrors on which no dust has fallen, clear receptors of their world. As opposed, then, to the characters in this novel, whose perceptions are all cloudy from experience, disappointment and desire. It’s a really unique and unusual novel, quite unlike anything else I’ve read, I think.