This comes with thanks to Paula at Book Jotter for her Three Things meme!

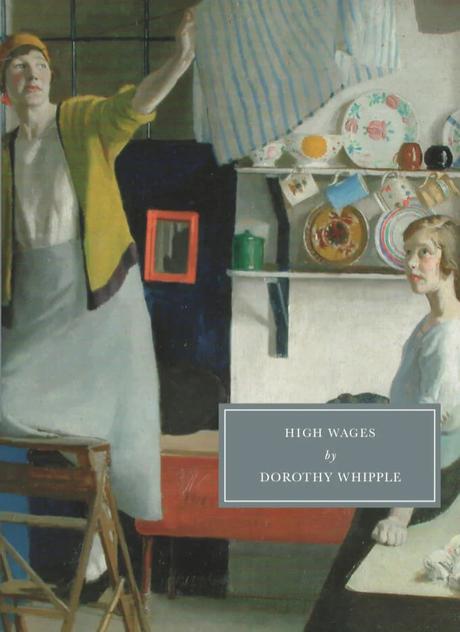

The Book: Earlier this week I had a sudden yen for a Persephone title and picked up High Wages by Dorothy Whipple. I’m so happy that I did. I’ve enjoyed all my reading lately but this is the first novel in a long while that’s held me properly hostage, that I put down with the greatest of reluctance and pick up again at the first available opportunity. It’s the story of Jane Carter who, at 17, is obliged to make a living for herself, having trespassed on her stepmother’s goodwill for too long after the untimely death of her father. She finds work as a shop girl in Chadwick’s, a draper’s shop as it was called, where women came to buy material and trimmings that would then be made up into clothes by their off-site seamstresses. It’s 1912 and the great shopping revolution is underway. Selfridges having opened its doors onto an extravagant cornucopia of goods in 1909, and Jane, with her ‘good eye’ and determined ambition will be at its forefront. She will push Chadwick’s as far as she can towards the new, modern ways, and eventually set up a shop herself selling the fresh trend of ‘ready-mades’.

There’s a fascinating preface to the book that delves into the social history of shopping at this time, and the phenomenon that was the shop girl. Very few avenues of work were available still to women, and retail looked a great deal less arduous than either service in a house or factory work. In fact, it was as exploitative as most other forms of employment. Shop girls worked a solid 12-hour day with only 20 minutes for lunch and most lived in on the premises for a cut of their wages. Dorothy Whipple writes a brilliant villain, one of whom is the redoubtable Mrs Chadwick, who holds the domestic purse-strings in her tight fist:

Mrs Chadwick was rather mean. Not excessively so; but just mean enough to add interest to her days. She enjoyed exerting her ingenuity in the provision, for the girls, of suppers that did not cost more than threepence a head.’ And when the First World War comes, it ‘called Mrs Chadwick’s full powers into play; she lived vividly. She could now scheme and stint to her heart’s content…. She spent exciting moments stealing down to her own scullery, when the girls were out of the way, to take parings from their margarine allowances with a razor blade. She would pop the stolen pieces into the pot where her husband’s supper was cooking… with a greater satisfaction than she had known when she could put ounces of the best butter in and never miss them.’

Jane is permanently hungry while she’s at Chadwick’s, but the disadvantages of life there keep her motivated to move on. Shop girl literature – and there was such a thing – fell into two categories. On the one hand, commercial romances in which the pretty girl behind the counter is plucked from obscurity by a well-off prince and may return to buy goods on her own account; and the rags to riches and possibly back to rags tale, where dangerous social aspirations were met with scandal or worse. Whipple’s book takes a different, kinder, more optimistic path, although Jane’s route to better fortune is punctuation by misunderstandings, hardship and betrayals. And finally – finally – I have a book in my hands in which the main female protagonist chooses work over romance; I’m cheering her on.

by Pearl Freeman,photograph,1930s

" data-orig-size="220,300" sizes="(max-width: 220px) 100vw, 220px" data-image-title="NPG x46529,Dodie Smith,by Pearl Freeman" data-orig-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/dodie_smith.jpg" style="width:220px;height:auto" data-image-description="" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"0","credit":"National Portrait Gallery London","camera":"","caption":"by Pearl Freeman,photograph,1930s","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"\u00a9 National Portrait Gallery, London","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"NPG x46529,Dodie Smith,by Pearl Freeman","orientation":"1"}" width="220" data-medium-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/dodie_smith.jpg?w=220" data-permalink="https://litlove.wordpress.com/2025/05/09/three-things/npg-x46529dodie-smithby-pearl-freeman/" alt="" height="300" srcset="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/dodie_smith.jpg 220w, https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/dodie_smith.jpg?w=110 110w" class="wp-image-5554" data-large-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/dodie_smith.jpg?w=220" />Dodie Smith in the 1930sThe true story: Perhaps one of the best stories of a shop girl made good concerns the author of 101 Dalmations and I Capture the Castle, Dodie Smith. Dodie’s first desire was to be an actress, and from 1914 she was a very bad actress indeed, one who, in her own words, was always ‘talking herself into a job and then acting herself out of it.’ She lurched from one bad role to another, until finally she seduced the director of the Windmill Theatre, Norman McDermott, in the hope that it would guarantee her steady employment. In fact he sent her abroad on tour and then, in her absence, sacked her. And so, Dodie decided that part of her life had come to an end and she needed a new direction. In 1923, she heard of a position in the London furniture emporium, Heal’s, and went and talked herself into that. ‘After years of selling myself as an actress to theatrical managers who didn’t want me,’ she wrote in her memoirs, ‘it was child’s play selling goods to customers who were pleased to have them.’

When she turned out to be a success, she went directly to the manager, Ambrose Heal, and (just like Jane Carter in Whipple’s novel) negotiated herself a pay rise. This was considered outrageous presumption, but Ambrose Heal was inclined to be charmed by it, and Dodie needed no more encouragement. She longed to be in love again, and had acquired a taste for sleeping with the boss. She’d unwittingly set herself a challenge, though, as Ambrose Heal had not only a wife, but a mistress too. When he pointed out how little time and affection he had to spare, she told him ‘half-a-loaf was better than no bread’. To his continued protests, she said ‘Then just crumbs from the rich woman’s table.’ So Ambrose Heal accepted defeat, and for the next six years they maintained a stable if clandestine affair.

During this time, Dodie was busy channelling her energies and ambitions into her writing. Ever since she was a child she had written stories and plays but acting had always been her passion. When Ambrose Heal gave her the rather splendid gift of a typewriter for Christmas 1929, she longed for something to type up. As it happened, she had an idea for a play. Playwriting braided together Dodie’s finest skills – a powerful sense of emotional melodrama inherited from her mother and grandmother, balanced by a rather delightful sense of humor. She had a fine ear for dialog in a family that loved a punchline. Her aunt looking with dislike at her hat in the mirror had declared ‘Well, it’s a beast and that’s all there is to be said about it’. Dodie had been relishing dialog for years, and she had her own wealth of stage experience into which she could pour her vivid imagination. She wrote her play quickly, loving the experience, and her triumph was complete when it was bought by a director who had once sacked her.

The first night was catastrophic – a rumpus in the audience ended with the gallery booing the play and the stalls booing the gallery. ‘I never heard a noisier, more disastrous, reception’ Dodie remembered, and she went to bed distraught, fearing the play had failed and thinking ‘But it can’t, because if it does I can’t bear it.’ Then in the morning, a miracle happened; the newspaper critics were uniform in their praise. Journalists rushed to Heal’s to get a glimpse of the latest sensation, a 33-year-old woman who ran her own department. By the evening news the billboards proclaimed: ‘Shopgirl Writes Play’.

For the next year, Dodie struggled to repeat her success, starting over and over with different ideas, none of which took fire. A journalist rang her up, asking whether she had anything new ready, and a theater critic wrote a story claiming that no woman had ever written more than one successful play. ‘Perhaps,’ Dodie wrote acidly, ‘they felt “Shopgirl Writes Play” had been a pleasant fluke, but “Shopgirl Writes Two Plays” would be a bit like Cinderella getting two princes.’ It seemed to goad her on, though, and she had the inspiration of writing about a grand department store suffering in a time of slump. At the end of the first curtain call for Service, she was enticed on stage to take a bow before the audience. It was a heady moment, hearing their whoops and cheers, finally finding her place on stage in the limelight.

Dodie Smith would go on to have three more stage hits, making five in a row which was a record for a woman playwright. She had the success and the money that she’d longed for, and she realised that her interest in Ambrose Heal had faded away. ‘I partly longed for affairs as status symbols,’ she wrote in her journal many years later. ‘Women have for so long been conditioned to equate sex appeal with success.’ Her plays fed her ego far more than any mere man could, and in comparison the romance of an affair felt paltry. And so I keep banging the drum: women want work; stop giving them storylines that are all about the men.

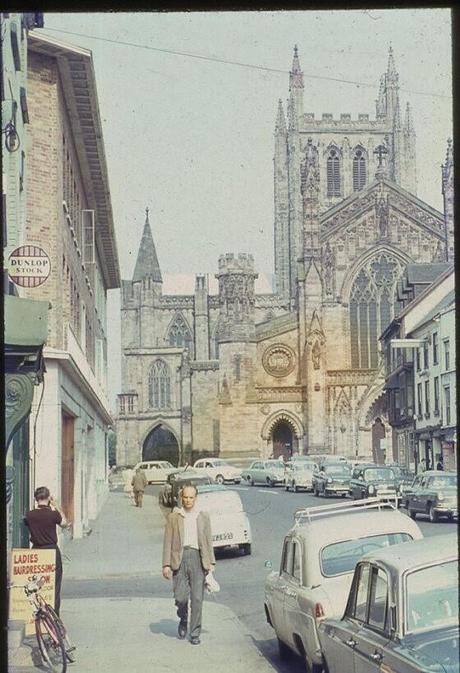

The photos: A few weekends ago I was with my family, searching through the thousands of family photos we’d taken over the years for good ones of my Mum, when my brother remembered the slides up in the loft. He returned with four old boxes, each about the size of a large dictionary, each divided up into about a hundred tiny compartments, each of which housed a slide. We held them up to the light in awe of their antiquity, squinting to see the tiny figures. Well, my brother took them away and scanned them onto his computer, producing a very 21st century One Drive file with almost 500 photos on it. This, for me, was my family prehistory. The life they had together before I arrived in it – well, there’s a sequence towards the end of the slides of me as a baby, and a handful in which I’m a toddler. It is so very strange to see my parents and brother before I knew them. My brother at 5, 6, 7, wearing shorts and a little shirt with a tie (a tie!), taken on holidays and trips, playing with his model railway. Mr Litlove looked at the photos and sighed ‘He’s living the dream,’ he said. I did feel a tad guilty; my arrival must have been a bit of a shock.

But the pictures that fascinated me the most were the location shots. This was only the 1960s, less than a decade before I was born. But the small towns depicted look like they come from another world altogether, a world that is probably less distant from that of High Wages and Dodie Smith’s time at Heal’s than it is from the High Street as we know it today.

This was the world in which my parents were young and it makes me feel very old. I don’t know where these photos were taken, but think it might be from the area around Hay-on-Wye. If you recognize it, do let me know!