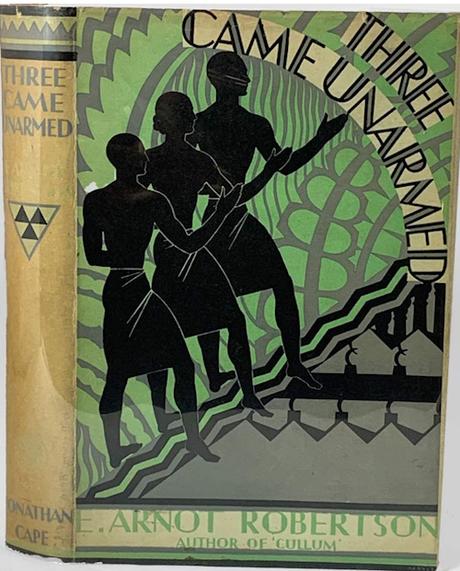

Book review by George S: This novel begins brilliantly, with a virtuoso description of a young man stalking babirusa, the wild pig of Borneo. He is at one with the jungle: ‘the lithe brown body crawled noiselessly, moving surprisingly fast as a snake can.’ The hunt is only partly successful, because he is diverted from hunting the pigs when a larger jungle creature threatens. He escapes from this, but finds a plandok, a gracefui little deer scarcely bigger than a hare. He ‘maimed it with a fortunate throw as it bounded away, killed it with his hands, and came home delighted.’

Herel is one of three children of an English missionary who turned to drink and lost his faith. The others are Nonie, a very beautiful young girl, and Alan, who is artistic. The children have been left to bring themselves up, and all three have the qualities that Herel displays in that first chapter – naturalness, determination, and a complete lack of sentimentality.

When the father dies, the children have instructions to go back to England, and they do so by themselves, working their passages on ships and barges. When they finally reach their relatives at West Mersea, on the Essex coast, they enter a world very different from the Malaysian jungle.

Robertson uses her three strangers as a fictional device that by contrast brings out the artificiality of English society, and she indulges in enjoyable satire, especially at the expense of their aunt, Mrs Evered, who likes to consider herself as an advanced thinker, but is actually utterly conventional.

When the three strangers arrive, she loves to picture herself as their saviour, and expects them to be grateful. She has sentimental ideas of noble savages, which the trio just won’t conform to. When finally she accuses them of ingratitude, Herel points out that she has all this time been living on his father’s money, which is actually, by the terms of his father’s will, his own and not hers.

All three are puzzled by English conventions and hypocrisies; the tough life of the jungle has made them used to living realistically, without paying lip service to any social conventions. They do, however, find two people with whom they can connect -an invalid woman and her doctor, who both have clear-sighted, realistic views of life.

In Kapel Pechah the three had been expert sailors of small craft, and they prove equally expert with the boats of west Mersea. Robertson knows what she is talking about; even more virtuoso than the hunting chapter at the start of the book is a chapter in the middle, where Herel and Nonie take an unreliable craft round the Essex coast in a storm. Real edge-of-the-chair reading.

Alan, the younger brother, is an artist who loves beautiful things. His lack of sentimentality means that he gets a local girl pregnant and deserts her. Later he is led into petty crime by a dishonest art connoisseur. Meanwhile, Nonie falls in love with the doctor who is obsessed only by his work. Herel, who loves machinery, goes to work in an uncle’s paper mill in the north. He modernises the machines, but makes himself very unpopular with the workers – Robertson is as unsentimental about the Northern working class as she is about the gentlefolk of West Mersea. When the new machines mean lay-offs, especially of men who have proved themselves unreliable, an unreasoning mob attacks the factory at night and destroys it, despite Herel’s attempts at defence. Another virtuoso piece of action writing.

The novel is consistently absorbing. Robertson’s treatment of sex is frank, and she is particularly lethal at exposing the romantic self-deceptions of Dawn, Mrs Evered’s daughter. Among her other targets are religion and the war that Christians had sentimentalised. She has one character talking of:‘the war that, for nine out of ten thinking people under middle age, burst the sweetly coloured Christian soap bubble as blown by the churches.’

As a novel it is not perfect. The wise yet innocent savages sometimes seem more literary device than rounded characters. And the wise invalid Mrs Ackland is used as an author’s mouthpiece more than as a person with a role to play in the plot.

But this imperfect novel is much better than some more skilfully crafted ones I have read.