City of Spades by Colin MacInnes

Colin MacInnes is one of those classic London writers now slipping slightly from view. I tend to think of him in the same mental breath as Gerald Kersh (though Kersh was a generation earlier). Both share an interest not just in characters but in capturing a time and place.

MacInnes is best known for his London trilogy, three thematically linked novels about youth culture and black culture in 1950s London. It’s a time as far from us now as the Victorians were from MacInnes and a decade that’s often oddly ignored. We skip from the war to the ’60s, leaving the austerity years as unexplored archives of conformity; a breathing space between the struggle for survival and the arrival of the counter-culture.

Of course, that’s nonsense. The 1950s were a period of tremendous social change. The Empire Windrush brought its first West Indian immigrants in 1948, but it was the closing of the US to Afro-Carribean immigration in 1952 coupled with a desperate local labor shortage that led to the arrival in the UK of large numbers of Afro-Caribbean immigrants throughout the ’50s. There had long been a black British population, but never in such numbers.

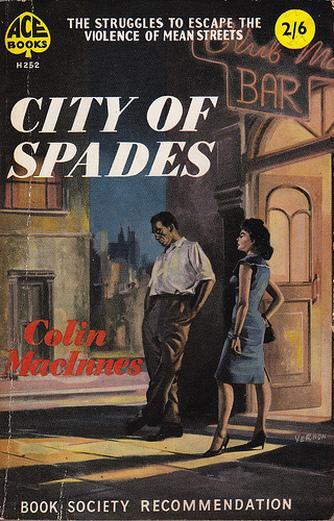

The second cover is the one I have, but is completely misleading and rather notably doesn’t include any black characters. The first is a bit melodramatic, but I at least recognize it as relating to the book I read.

City of Spades opens with Montgomery Pew starting his first day at his new job at the Colonial Department. He’s responsible for helping settle new Commonwealth arrivals to the UK. In practice that means Africans and West Indians, people Pew has never met before and has only the vaguest generic impressions of. He admires their “sleek, loose-limbed appearance” and “elegant, flamboyant style of dress”, but deplores “their dismal spirituals and their idiotic calypso”. He draws no distinction at all between African and West-Indian, and isn’t even aware there might be further distinctions within those categories.

His first client is the newly arrived Johnny Fortune, come to England to study meteorology for a year. Montgomery, a quiet sort, is slightly dazzled:

I observed that he was attired in a white crocheted sweater with two crimson horizontal stripes, and with gold safety-pins stuck on the tips of each point of the emerging collar of a nylon shirt; in a sky-blue gaberdine jacket zipped down the front; and in even lighter blue linen slacks, full at the hips, tapering to the ankle, and falling delicately one half-inch above a pair of pale brown plaited casual shoes.

Johnny refers to himself as a Spade. Montgomery is something of a liberal and as such is concerned that this might be an offensive term. Johnny admits it’s a bit “cheeky” but much preferred to most of the other local terms. To him Montgomery is a “jumble”, adapted from John Bull. It’s all getting a little out of hand, particularly when Johnny inquires why there’s a problem placing him with a white landlady when back home nobody has an issue with Jumbles staying with Spades. Montgomery moves the conversation along:

I took up the Warning Folder of People and Places to Avoid. ‘Another little duty for which I’m paid,’ I said to him, ‘is to warn our newcomers against … well, to be frank, bad elements among their fellow countrymen.’ ‘Oh, yes, man. Shoot.’ ‘And,’ I continued, looking at my list, ‘particularly against visiting the Moorhen public house, the Cosmopolitan dance hall, or the Moonbeam club.’ ‘Just say those names again.’ To my horror, I saw he was jotting them on the back page of his passport.

Montgomery decides to look into the immigrant-only B&B Johnny’s been housed in to see if it’s really as bad as Johnny complained. From there he finds himself drawn into Johnny’s life, and an unlikely friendship develops.

The chapters alternate between Montgomery’s and Johnny’s viewpoints. Johnny’s father visited London years past himself and asks Johnny to look in on his old flame, Mrs Macpherson. She’s now an embittered woman, her life ruined by an illegitimate child left her by Johnny’s father, a half-brother Johnny never knew he had. She has two daughters, the older now turned to prostitution after getting involved with a sinister Gambian named Billy Whispers and the younger catching Johnny’s eye.

Montgomery meanwhile introduces his neighbor Theodora to Johnny. She has a highly paid job at the BBC and while Montgomery’s a diffident sort Theodora is ambitious and driven. She’s attracted first by the intellectual puzzle Johnny and his acquaintances present, what they want and why they’re “here”, but before long she’s attracted too by Johnny’s charm.

MacInnes draws out a world of late night bars, underground clubs and petty crime. To Montgomery and Theodora Johnny and Billy Whispers and the others they meet in Johnny’s world are all blacks, part of the same undifferentiated culture. They don’t pick up the tensions between the Gambians and the Nigerians, the mutual mistrust between the Africans and the West Indians, the disdain the city-Africans hold for the country-Africans, and the way all of them prey on the innocence and relative wealth of the black GIs.

Montgomery and Theodora are both sharply drawn characters, but it’s the black characters here who mostly stand out. Perhaps that reflects Montgomery and Theodora’s own fascination, or perhaps it reflects MacInnes’ experience. Whatever the reason, most of the whites are rather gray characters, whereas among the blacks there’s Billy Whisper and his gangster-cohort Jimmy Cannibal and Ronson Lighter, casual drug dealer Peter Pay Paul, serious-minded intellectual Karl Marx Bo, calypso artist Lord Alexander and many more.

The book follows Johnny’s adventures as he gets mixed up with Billy Whispers and his crew and finds himself in trouble with the police, who make rather a point of rounding up everyone sooner or later. In parallel, Montgomery finds there’s a cost to getting too close to the “colonials” he’s supposed to be looking after, attracting his superior’s suspicions without ever truly becoming one of the people he so admires. When challenged Theodora thinks it’s ok for whites to marry blacks, but not for blacks to have self-rule. Montgomery is fine with the political freedom, but not with inter-racial marriages “For the child’s sake.” Both mean well, but as Karl Mark Bo rightly observes:

‘Well,’ he said, ‘you are both nice people, I am sure, but I think you also are what we despise even more than we do those who hate us – you are full-time professional admirers of the coloured peoples, who like us as you like pet animals.

The obvious difficulty with City of Spades is that it’s a book that’s in large part about black British experience, but written by a white author. While that could be a problem, MacInnes’ particular interest is in how the communities bump against each other, changing and being changed. He shows too the sheer complexity and diversity of experience, the fact that it isn’t two communities as commonly described but a small myriad. Just as Johnny has little in common with the “Bushman” he mocks as being from the interior Theodora has little in common with the embittered and working class Mrs Macpherson.

MacInnes is strong too on the clash of expectations. Theodora asks “why do they flock here to England?”, as if there were one single reason motivating so many different people. In a later scene a West Indian named Tamberlaine imitates the typical conversations he encounters, the banal questions such as ‘“Don’t you miss the hot weather over here?”’ and well-meant comments such as “You may find, sir, that there is sometimes a certain prejudice in England, but believe me, sir, that some of us are just as worried about it as you.”’

Most mocked of all though is when the whites say “I like coloured people, myself.”’ None of the black characters here mind being liked for themselves, but unsurprisingly none of them take too kindly to being liked just for being black.

Montgomery and Theodora aren’t racist in the manner of Mrs Macpherson or Montgomery’s predecessor at the Colonial Office, but through all that happens they still see the characters they meet not so much as individuals but as representatives of a type. Montgomery thinks of Johnny as a friend, but Johnny’s more circumspect on the point seeing too clearly Montgomery’s tendency to stereotype and to lecture him for his own imagined good.

For all the seriousness of its intent City of Spades is generally extremely funny. Montgomery and Johnny are both likable characters and their London is an enjoyable place to visit. The future’s being born, a new and better Britain, and both MacInnes and they know it.

I’ll end with a little calypso, courtesy of Lord Alexander. Montgomery wouldn’t approve, but Johnny probably would:

“This little Miss Commercial Road she say to me,

“I can’t spend much more time in your society.

I know you keep me warmer than my white boys can do,

But my mother fears her grandson may be black as you.”

Somehow it captures the book for me.

Other reviews

None on the blogs that I know of, but I found a tremendous review at a site called London Fictions here. For a different perspective on the period I can’t recommend too strongly Sam Selvon’s spectacular The Lonely Londoners, which I reviewed here.

Filed under: MacInnes, Colin Tagged: Colin MacInnes