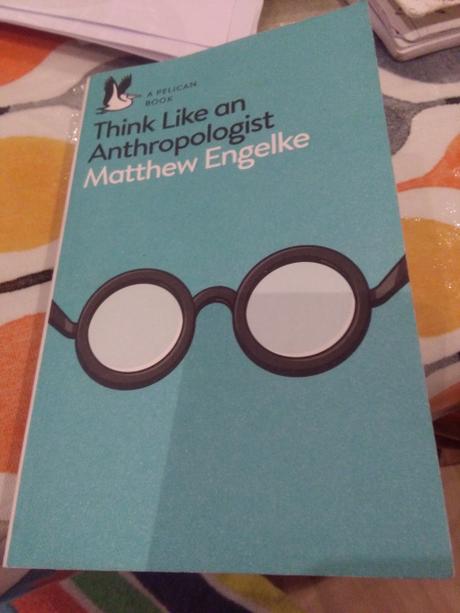

This is the alluring title of a book I recently read. Look at the picture below and you will see that the volume itself is rather attractive: a very satisfyingly textured cover of a delicate turquoise in minimalist design.

As someone who remains deeply fascinated by people, both at the level of the individual and the collective, I was keen to find out how to hone my thinking skills in understanding and making sense of human beings. Who doesn’t want to know about culture and society? Its aligns with all those big existential questions around making sense of who we are, what is our place in the world, what makes us special and what connects us with others.

However, it seems that turning this into a formal branch of academic study makes getting all the answers to these grand questions rather problematic. You end up getting bogged down in layer upon layer of caveats and additional questions; and it seems that learning to think like an anthropologist is actually about learning to understand how our attitudes towards understanding societies and cultures has changed over the past 150 years.

The problems begin when thinking about the central area of focus – culture – which seems like a good solid concept but the more you try to ‘go somewhere’ with it, you realize that it is actually a slippery thing which has slipped away.

This is addressed in the first chapter which sets out how culture has been interpreted differently over time, showing therefore that it is a subjective concept. It has limitations. Let’s think about some concrete examples.

You cannot connect culture with a place too tightly, contrary to what we might initially think. As the author notes,

“What if we want to get even more specific? Can we speak of ‘London’s culture’? Or do we need to be more exact and speak of third-generation Bangladeshi Britons in Tower Hamlets? …And yet further, can we necessarily call someone whose grandparents came from Sylhet to East London in the 1970s a ‘third generation Bangladeshi Briton’? What if they couldn’t care less about ancestry? What if they consider themselves a ‘native’ Londoner?”

Nor is culture fixed in time. The author gives the example of some seminal studies done on tribes in Zimbabwe but in these “the Ndembu are presented very pristinely, as if the huge political and economic challenges and changes taking place simply didn’t register.” In fact, at that time, the 1950s and 1960s, North Rhodesia was full of anthropologists studying culture change and the dynamics of culture change in emerging urban centres, but it is that atemporal study on the Ndembu that has the biggest impact on students!

And then when you try to make sense of has been found out, it is necessary to make analogies to what is already known and understood. In other words, all understanding is relational and more revealing about the attitudes of the one interpreting than providing insights about the subjects of anthropological study. It seems that the dangers come when trying to make the leap from the observed specific to general theories or principles onto which to hang all these little ideas. The theoretical packaging that goes around it all reflects more of our values. It is the study of the particulars that stands the test of time – ethnography – spending time with people to watch how they behave and what makes them tick.

As a curious consumer (in all senses), I think I am doing that already, thank you.

Advertisements