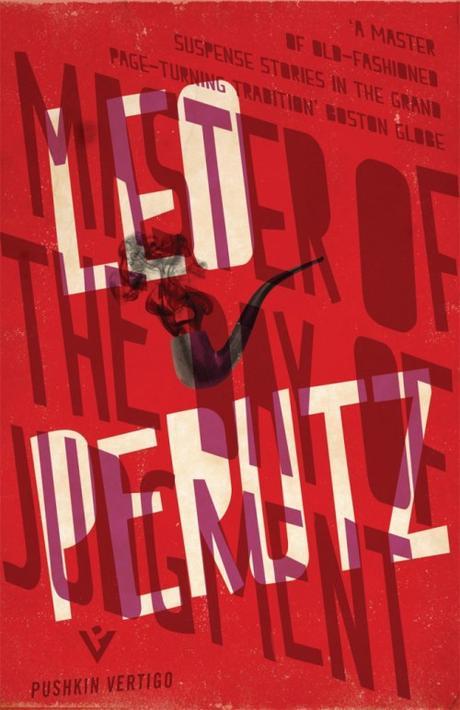

Master of the Day of Judgment by Leo Perutz, and translated by Eric Mosbacher

Early 20th Century Vienna has to be one of the most fascinating periods and settings in literature. The end of the Austro-Hungarian empire saw an explosion in talent: Robert Musil, Joseph Roth, Arthur Schnitzler, Ernst Weiss; Stefan Zweig (and that’s just the ones I’ve personally read). Vienna in particular was a hotbed of ideas: Marxism and Freudianism offered new models of society and the individual, each of them challenging established traditions and philosophies.

It’s a natural setting for a crime novel, so much so that author Frank Tallis has set a successful series there with a disciple of Freud as his detective. Long before that though there was Master of the Day of Judgment, written in 1921 by a Viennese author steeped in the passions of his time. It is, quite simply, brilliant.

Baron von Yosch is a soldier and aristocrat. He is setting down, for who knows what audience, his recollection of a terrifying series of events that occurred some years previously in 1909. He insists on the accuracy of his memories, down even to remembering minor newspaper stories of the day on which everything started. He insists so strongly in fact that immediately I began to wonder, why is the Baron so keen to persuade me he has forgotten no detail no matter how small?

Among the newspaper stories that day was a bank failure. Baron von Yosch had already moved his funds, but he knew his friend Eugen Bischoff had not. The Baron could have warned Eugen of the impending collapse, but as he reflects:

… would [Bischoff] have believed me? He always regarded me as a retailer of false information. Why meddle in other people’s affairs?

The Baron seems then a somewhat cold individual. A man whose friends don’t trust him, and who cares so little for them in turn that he won’t even try to warn one of possible ruin. This is our narrator; our guide to the events that claimed several lives. The Baron’s foreword gives us a premonition that whatever happened must have been truly terrible, and I found myself briefly reminded of Perutz’ contemporary H.P. Lovecraft:

Thus the whole sinister and tragic business lasted five days only, from 26 to 30 September. The dramatic hunt for the culprit, the pursuit of an invisible enemy who was not of flesh and blood but a fearsome ghost from past centuries lasted for just five days. We found a trail of blood and followed it. A gateway to the past quietly opened. None of us suspected where it led, and it seems to me today that we groped painfully step by step down a long dark passage at the end of which a monster was waiting for us with upraised cudgel. The cudgel came down twice, three times, the last blow was meant for me, and I should have been done for and shared Eugen Bischoff’s and Solgrub’s dreadful fate had I not been snatched back to life in the nick of time.

…

Sometimes sheer terror seizes me and sends me to the window, feeling that the dreadful waves of that terrible light must be rushing across the sky, and I cannot grasp the fact that overhead there’s the sun, concealed in silvery mist or surrounded by purple clouds or alone in the endless blue and round me wherever I look are the old, familiar colours, those of the terrestrial world. Since that day I have never seen again that fearful trumpet red.

It sounds like a work of gothic or cosmic horror, but it’s soon apparent that it’s not quite that simple. In fact, despite coming in at comfortably under 200 pages, nothing in this novel is simple.

Eugen Bischoff is a famous actor whose best days are past. His career is sharply in decline and now he has lost his life’s savings. The morning’s newspaper has been hidden from him so as to ensure he doesn’t get the news cold, and his friends have gathered round to support him, the Baron among them.

We know of course that Bischoff will die, the Baron’s foreword listed him among the victims. What we learn quickly is that Eugen is married to the Baron’s former lover, a woman the Baron still has feelings for. It’s a source of tension, and matters worsen when the Baron accidentally makes reference to the day’s events in ways which might give the game away. Well, the Baron’s writing the story and he says it’s accidental, but everyone else present seems to think he’s toying with Bischoff and amusing himself by seeing how far he can push the frail actor.

Bischoff leaves the room, and shortly afterwards two shots are heard. The Baron rushes to the scene where he finds Bischoff dying, a mutual doctor friend present but too late to save him. Bischoff casts a final gaze at von Yosch filled with pure hatred and speaks his last words – a reference to the day of judgment.

Almost everyone concludes that the Baron followed Bischoff, told him of the bank’s failure and gloated over him until Bischoff in panic and despair took his own life. The Baron however swears on his honor that he only entered the room after Bischoff already lay dying. Only the engineer Solgrub believes the Baron, and he sets out to discover what truly led to Bischoff’s death.

There are two mysteries here. One is why Bischoff killed himself. The other is why everyone who knows the Baron is so quick to believe he could be responsible. His former lover clearly blames him for her husband’s death, and her brother Felix demands that the Baron should take his own life as payment for his crime. Whether the Baron forced Bischoff into suicide is up for debate, whether he was capable of such an act however seems to be much more clear-cut. Even he is not entirely certain, at times remembering himself in the room and then dismissing the memory as false and produced by the stress of the situation (but notably not as out of character).

Solgrub’s investigation soon leads him to suspicions of another agent in the drama, a mysterious Dr Mabuse-like figure able to force men to suicide simply by forcing his will upon theirs (interestingly the novel Dr Mabuse, Der Spieler was also published in 1921). Solgrub and Felix agree then that Bischoff’s suicide was prompted by a third party, they just differ on whether that was von Yosch or this mysterious stranger. The Baron meanwhile reckons that he can solve the mystery himself, but soon finds his investigation overlapping with Solgrub’s.

At various points this moves from being a tale of gothic horror to a locked room mystery, to an amateur detective story and back again, but in truth it’s more than all of those. It becomes like so many good Austro-Hungarian novels a tale of psychological suspense. Solgrub is racing against time as the Baron, without even consciously realising what he’s doing, begins to make preparations for his own suicide. Society’s judgment demands that the Baron satisfy the demands of honour, and Solgrub is the only man truly convinced of the Baron’s innocence.

After a young failed artist connected with Bischoff also commits suicide, Solgrub strives to find a connection between the victims and to persuade Felix that there’s a common culprit. A hypothesis emerges that the slain may have willingly risked insanity and death for artistic inspiration; that creativity and terror draw from the same deep interior wells and that their own ambitions were the cause of their destruction. Now Solgrub wants to know what the dead knew, and we know from the foreword that before the story’s out he’ll join them.

That foreword casts a shadow over the whole narrative. We know the Baron lives and Solgrub dies, but not how or why. We don’t know what that “trumpet red” that von Yosch so cryptically referred to could be, or what exactly still terrifies him years later as he writes his account. As I raced towards the end I found myself asking more and more what kind of book I was reading, whether this was supernatural horror or psychological or something else altogether.

I’ll leave that last puzzle for each of you to answer for yourselves. The journey and the destination both are too satisfying to be lightly spoiled.

Other reviews

Only one on the blogosphere that I’ve found, by David Auerbach here. The Auerbach review gives away a bit more than I have, but not remotely fatally. I’ll also caution against the review in The Independent, which while positive I think rather misses the point of the book.

Filed under: Austro-Hungarian Literature, Perutz, Leo, Pushkin Press, Pushkin Vertigo Tagged: Leo Perutz, Pushkin Press, Pushkin Vertigo