Data and collection of information is a necessary stage in an inventive process. The process can be thought of as a black box filled with information related to the design that should be processed and new creative ideas should as a result emerge. But what sort of information should we put into the black box?

Paul Valerio says that we should learn from two target audiences to help us with future design works: astronauts and children.

When you search for data, you tend to look for relevant information and avoid data and information containing noise. Yet design insights are often the result of an active exploration of noise. Paul Valerio says noise is much more valuable than you might think.

By exploring data from a child’s or an astronaut’s perspective or point of view, we may can insight into problems we may encounter when we try to use the data as a base for new designs. We often assume that the data we collect is:

- Free from distortion

- Is the sum of all the individual variables that underlies the data ( assuming linear relationship is the simplest way, yet additional information may reveal a wider range of possible dependencies)

By exploring the data from the perspective of an astronaut’s visiting the moon, we may learn how the lack of atmospheric haze influences the perception. On Earth, distant objects appear lighter in color than closer things. But on the Moon, everything looks sharp. There is also no reference point, such as trees and houses on the Moon. The astronauts were trained and they had experience of distance judgement, yet they had problems when they landed on the Moon. Rather than supporting the astronauts their expertise was the problem. It was difficult to use the expertise in a completely new environment. They need to break their own pattern of perception and use the new data in a foreign environment. Exploring data like an astronaut means changing perception.

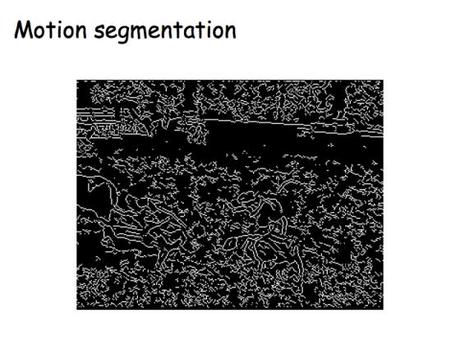

This image is unrecognisable. But when set into motion, you can see what is in the picture. Go here to play the animation (4 Mb mpeg movie).

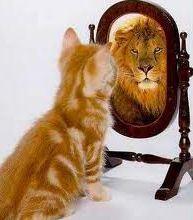

Children can “read” and understand pictures filled with noise. If you show a child a picture of an everyday scenes like an animal created from common objects. They can ignore the common objects and they see animal in the jungle. They can un-see the scissors hiding in the grass pretending to be the hare’s ears. Or the fruits used to made a picture of an animal. Exploring data like a child means looking for hidden patterns.

A child embraces the noise while the astronaut is confused and baffled by it. Paul Valerio says; “No matter where your data comes from, think about what has been omitted. Was that distracting noise that was tossed, or crucial context?”

Our ability to create pattern is often considered as a way to help us make sense of our environment. Yet breaking the pattern can help us gain valuable insight that we can use to design, invent, or search for solutions to our problem. Moreover, stepping away from the idea that perception is something that is a lonely process that takes part in our brains is also helpful. We create patterns and perceive situation not simply based upon what in our heads. It is a dynamic process between our brains and the environment. For example, vision is not a passive process – it depends at least partly on the interactions between us and the environment Imagining what our data looks like by placing them in new environments and scenes is engaging and it might be helpful as well. . .

Photo: Paul Valerio Photoshop Contest.