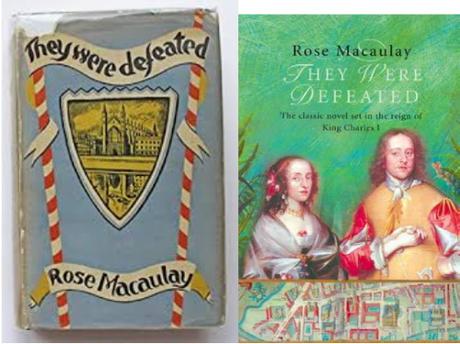

Book Review by Mary Grover: They were Defeated was said to be Rose Macaulay’s favorite novel. Published in 1932, this historical novel about intellectual life during the mid seventeenth century was well reviewed but never proved as popular as her contemporary novels.

There is a double focus: the poetry and opinions of the real poet Robert Herrick, an unconventional country parson, and the fictional Julian, the androgynously named daughter of an atheistic doctor. The vulnerability of this teenage girl in her quest for an intellectual life shapes the narrative which is played out against the theological debates of the male poets and the approaching civil war.

As always, Macaulay is never dull but her ambition to write a novel which is informed by her historical and linguistic research, sadly made this this heavy-going for me. Too often a sentence creaks under the pressure to convey historical matter. Even this short sentence is labored: ‘All was gay, tranquil, lovely, English, like the Henry Lawes air that Mr. Herrick sang, to his own words, as he walked.’ (p. 82). The seven commas suggest the pressure to pack in the information about the composer who most frequently set Herrick to music and to create the context of Herrick’s creative life. I think it would be difficult to find such an awkward sentence in any other work by Macaulay. It illustrates one of the pressures of an historical novelist, especially one that combines real and fictional characters: the pressure to introduce the history that the fiction explores. Macaulay’s research into the lives and debates of seventeenth century poets and theologians is extensive and the dramatisation of these debates is, of course, always interesting but it makes the narrative wooden at times.

The other pressure is to use a language that conveys the period without locking the general reader out. Macaulay meticulously uses idioms of the period and words that have either disappeared or were used differently in the 1930s. The poor members of Herrick’s congregation are ‘the vulgars’ and Julian is described as a maid who ‘fonds on learning like a spaniel on bones’. I never doubted the authenticity of the speech but its unfamiliarity checks the reader’s immersion in the narrative.

The tragedy at the heart of the book is compelling. A girl with the apparent good fortune to be the daughter of a man who values her intelligence and to be tutored by the benign Herrick, is nevertheless destroyed by men who perceive women unworthy of education. The chapters describing the way her attraction to the non-fictional John Cleveland leads her to accept his casual contempt for her intellect are distressing. But the seduction of Julian is unconvincing. It is difficult to imagine a girl so intellectually sophisticated sitting like a dummy while her lover tears up her thesis on Descartes. She is reduced to a zombie in his company. And the way she dies, imposing herself between the blows of her brother and her lover is strangely stylised. The passages involving Julian are quite different from the passages when Herrick is in dialog with his fellow poets. Odd though Julian’s passivity is, it is shared by the central female figures of some of Macaulay’s contemporary novels for example The World my Wilderness and Crewe Train. In her review of Crewe Train Frances Soar describes Denham as ‘reluctantly compliant’; Julian too colludes in her own destruction. It is strange that the portrait of a young woman whose tragic loss of educational opportunity would have resonated with so many of the book’s readers should be portrayed with such apparent detachment or could it be a fatalistic resignation to the inevitability of women’s intellectual deprivation?