A growing number of psychiatrists and psychologists in BC say they are successfully treating patients by harnessing the power of the patient's own brain waves.

Neurofeedback treatment has been studied for decades but remains controversial among scientists.

"This debate has been going on for a long time," says neuroscientist Randy McIntosh of Simon Fraser University.

"There's a long history of using things like neurofeedback to help someone refocus their brain."

McIntosh - a professor in SFU's department of biomedical physiology and kinesiology, and BC Leadership Chair in Neuroscience and Technology Transfer Across the Lifespan - said there is evidence that neurofeedback works for patients with certain conditions, even if there is disagreement about how or why exactly.

But as with any mental health treatment, "There is no one therapy that will work for everyone," he said.

"But it could work for some."

'Brain training'"Neurofeedback is brain training with the aim of increasing cognitive flexibility," says Victoria psychologist Susan Brock.

Brock, former chairman of the Canadian Psychological Association's quantitative electrophysiology division, said a healthy brain should be able to "switch flexibly between mental states" at the right times.

But conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), one of her specializations, can keep people "in a constant state of overstimulation, even when they don't need to."

That causes a loss of cognitive functioning for such patients, many of whom are first responders and veterans.

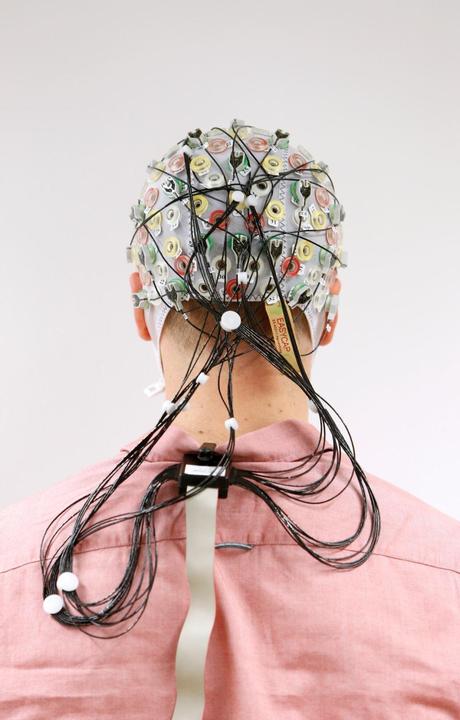

In electroencephalogram-guided neurofeedback, technicians place electrodes around a patient's head, as seen in this photo, to scan the electrical activity in their brain. Here the patient looks at a screen. (Craig Chivers/CBC)

The story continues

Electroencephalography-guided neurofeedback is offered by a number of private psychiatrists and psychologists in BC

In simple terms, the treatment involves technicians placing electrodes around a patient's head to scan the electrical activity in their brain, known as an electroencephalogram (EEG).

The EEG creates a kind of computer brain map, which can then be used by mental health professionals to promote a healthier state of mind.

Doctors use different methods to do this, but patients often watch a video while wearing the EEG electrodes.

If their brains exhibit unhealthy or unwanted electrical activity, the video becomes darker and quieter. But as their brain waves more closely match a "map" of healthy brains, the video gradually becomes clearer and more audible, as their EEG begins to reflect a healthier or calmer brain.

In fact, being able to enjoy a clearer video acts as a kind of reward or incentive to calm the mind and, the theory goes, slowly build healthy patterns.

The unorthodox approach is increasingly used among people with a range of mental health conditions, from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), according to doctors.

Brock said she has "seen a good response" in her decades of experience using the treatment. She said her patients often report troubling areas in their lives that "haven't really changed for the better," despite having tried various mental health therapies before.

Many still struggled with the ability to change their mental state when necessary, for example to calm themselves when they were upset.

"It's not that they don't want to change," Brock said. 'They don't know how.

"And for most, it's not a lack of trying; part of the beauty of neurofeedback training is that it happens at a subconscious level."

More data is neededAlthough primary care psychologists and psychiatrists say they see marked clinical improvements in many of their patients, researchers are divided on the efficacy of neurofeedback.

Several peer-reviewed studies suggest that better data is needed to prove that it works for the wide range of conditions that doctors claim to treat. The evidence appears strongest for ADHD, anxiety disorders and traumatic brain injury.

a Basic and clinical neuroscience A 2016 journal article found it to be "a safe and non-invasive procedure that has shown improvement in the treatment of many problems and disorders," including ADHD, anxiety, depression and autism.

But, the authors warned, "its validity has been questioned in terms of compelling scientific evidence of its effectiveness."

Another study, in the journal Psychiatric Clinics of North America compared multiple neurofeedback studies and found that they provided "significant benefits" for ADHD and anxiety and were "likely effective" for traumatic brain injury and substance use.

But the researchers said that "despite findings of positive outcomes" for depression and PTSD, the evidence remains "insufficient" without more rigorous or larger scientific studies.

Best combined with other treatmentsFor primary care physicians, the results are before their eyes - and in the experiences of their patients.

Four years ago, psychiatrist Dr. Kourosh Edalati Elumind Centers For Brain Excellence, with private clinics in North Vancouver, Langley and Kelowna. He offers neurofeedback, in addition to more conventional psychotherapy and medications.

"As an integrated model, we've seen very, very good responses," he said. "The principle behind neurofeedback is actually operant conditioning...which means positive and negative reinforcement.

"The brain learns that connecting to the right path is rewarding. With all the repetition, the brain starts to switch to the right path."

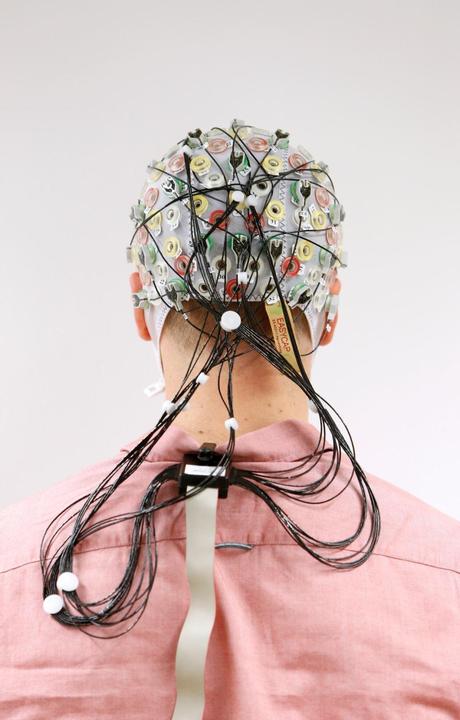

Test subject Niklas Thiel poses with an electroencephalography (EEG) hood that measures brain activity at the Technische Universitaet Muenchen (TUM) in Garching near Munich in September 2014. (Reuters)

By taking a multifaceted approach to treatment, says SFU's McIntosh, neurofeedback is probably best combined with other methods.

"We have to be very careful not to think, 'I'm just going to get brain stimulation that will make me better,'" he said. "Some people need extra support."

"It seems to work for some people... allowing people to loosen up."

But exactly how neurofeedback achieves that in the brain, he said, remains unproven.

"Why do these things work?" he said. 'The 'how' of it is a bit of a mystery.

"The evidence is quite good, but not conclusive."