Banner for North Carolina Opera’s Das Rheingold at Meymandi Hall

Banner for North Carolina Opera’s Das Rheingold at Meymandi HallPolitics and the Ring

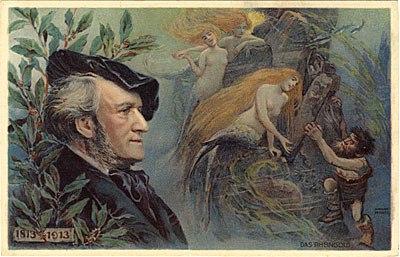

Richard Wagner, by the words and actions of those who knew and worked with him, was a horrid individual. He was also an incredibly perceptive musician. There were some who claimed he foresaw the direction of modern music with Tristan und Isolde. There were others who believed his theories on racial purity and professed anti-Semitism led to Hitler’s rise. Still others insisted he foisted immorality upon the operatic art form, along with similar related feats.

The truth may lie somewhere in the middle, but there’s no denying that Wagner was fully dependent on the (ahem) “kindness” of friends, to include their monetary and property holdings. What we do know about his so-called “theories” regarding music and drama is that Wagner laid the groundwork for a more politicized interpretation of his output, both through his writings and his musical compositions.

It’s a well-known fact that Wagner and his works can hardly be divorced from his tumultuous life, as volatile and meandering as it assuredly was. With all the difficulties he had with lenders and creditors; with his well-documented disdain for authority; with his amorous affairs with married women; and with his taking manipulative advantage of a young and gullible monarch, it’s a wonder that Wagner emerged as an artist of the first rank. In our day, we regard the personalities of even the vilest performers as being counterbalanced by their artistic accomplishments (for starters, try looking up “rock-n-roll lifestyle”).

Whether history can forgive Wagner his many transgressions — considering what he left behind as his legacy — must be left to posterity. That he was pilloried not only in his time but right up to the present day can be taken as a sign of his continuing viability as the architect of polemics. No better case for this claim can be made than in record producer and author John Culshaw’s Wagner, the Man and His Music, published by E.P. Dutton, in association with the Metropolitan Opera Guild and from which I quote the following passage:

“Wagner’s political activities did not stand in the way of his artistic creativity; indeed, to some extent the two were complementary, for since about 1845 he had been steeping himself in German history and legend. He read, among other things, the Volsunga Saga, the Nibelungenlied, the writings of the Grimm brothers and many other versions of Nordic tales. This was eventually followed by a scenario called ‘The Nibelung Myth as Sketch for a Drama,’ from which, very gradually and over many years, there emerged his conception of the Ring cycle.

“The connection between these writings and his political leanings is direct. He had not, of course, at that stage worked out or even thought out the implications of the Nibelung saga; it was simply that the quest for the Nibelung Hoard (which was gold) struck him as a symbol of the struggle for power. A simplified Marxist concept suited his position very well, for Marx propounded that the inheritance of wealth and property (and the power vested there) was a fundamental wrong. Wagner had inherited nothing at all, and yet those court officials who could not see their way to grant his talent whatever conditions he felt it required were themselves untalented aristocrats who had inherited wealth. The theory fitted like a well-tailored suit.

“It also confirmed the reason for the failure of his publishing venture, because the lack of capital had prevented the propagation of his works and consequently held his artistic ambitions in check. Two factors merged to bring out the political revolutionary in Wagner. One was the imaginative impact of legends he had been studying, for within them he could discern some symbolic patterns related to the German people (which gave him comfort, if only by suggesting that his predicament was part of the eternal condition of mankind); the other was the fact that his financial position was now beyond redemption. Nothing less than the downfall of the capitalist society and the substitution of some kind of social revolution, which might pay particular attention to the needs of Richard Wagner, would suffice to get him out of trouble” (Culshaw, Wagner, the Man and His Music, pp. 44-46).

Talk about self-absorbed! As indicated by the above, Wagner was entirely committed to his own personal and artistic survival, no matter the cost to his already questionable reputation. It would take another 28 years, give or take a few, for his vision, in the form of the Ring of the Nibelung epic, to take hold. The ultimate realization of his socio-economic and political ideas, this four-part cycle would receive its first complete hearing at the inaugural Bayreuth Festival in August 1876.

It has taken a lot longer than a quarter century to bring the Ring dramas to Raleigh. With that in mind, North Carolina Opera (or NCO), led by General Director Eric Mitchko, with the orchestra conducted by Artistic and Music Director Timothy Myers, has itself presented the first ever complete performance of a Wagner opera — in this case, the initial opera in the cycle, Das Rheingold, on September 16 and 18. It also happened to be the first full Ring opera given in the state of North Carolina, a historic contribution to the arts as a whole.

The Art of a Raw Deal

Four seasons ago, NCO presented a well-received concert performance of Act I of Die Walküre. The company continued the experiment two years later with a concert of the Prelude and complete Act II of Tristan und Isolde, starring Metropolitan Opera tenor Jay Hunter Morris as Tristan. For the recent Das Rheingold series, NCO decided on a “semi-staged” format as the best approach to the work, which included the use of props and costumes, as well as special video projections by the team of director James Marvel and projections designer S. Katy Tucker.

This being 2016 — a presidential election year — and with politics a hot-button issue with voters and broadcasters, for this writer Das Rheingold has become the perfect pre-curtain conversation piece, something to spark the usual “shop talk” we imperfect Wagnerites love to engage in.

For the uninitiated, Wagner wrote the “poem” (or libretto, to use the more common term) in reverse order, starting with Siegfried’s Death, which later became Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods”). Realizing he needed to provide additional expository information, Wagner then gave us Young Siegfried, shortened to just plain Siegfried. Still not satisfied, he went on to provide Die Walküre (“The Valkyrie”) and finally Das Rheingold (“The Rhine Gold”), the prelude to the cycle, although the text for both works was devised more or less simultaneously. The score was composed chronologically from that point on, beginning with the celebrated E-flat prelude to Das Rheingold.

By the end of Act II of Siegfried, after our hero has slain the fearsome dragon Fafner, and killed the treacherous dwarf Mime, Wagner put the Ring aside for a total of twelve years. He did this in order to labor over Tristan und Isolde — according to his convoluted rationale, an “easier” opera to produce — and his only romantic comedy, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

When Wagner picked up the Ring anew, he had matured compositionally by leaps and bounds, so much so that music and words flowed as never before. With Götterdämmerung, there was a noticeable change in color and tone, especially in his use of chromatics, which was felt most profoundly in his final stage work, the “consecrational festival play” Parsifal.

As to Das Rheingold’s political aspirations, one need only look to the opera’s main protagonist: I’m referring, of course, to Wotan, Wagner’s head god, our modern-day embodiment of real estate mogul and presidential candidate Donald Trump. There’s got to be an enterprising director somewhere, ready and willing to stage another of those modern-dress concepts using the Donald and his brood as stand-ins for Wotan, Fricka, Freia, Donner and Froh, not to mention Loge, Erda, the Giants, the dwarfs, and those seductive sea sirens, the Rhine Maidens. A smart producer, with eyes for satirical Saturday Night Live entertainment, could make mincemeat out this material.

Not to belabor the point, this would be the perfect time to delve into Das Rheingold’s “plot.” Grounding the story in present-day reality, our pretend Trump has struck up a one-sided real estate deal with the not-too-bright construction firm of Fasolt and Fafner, Inc. These two battling brutes, reminiscent of Tom and Ray Magliozzi, the bantering “Click and Clack the Tappet Brothers” on National Public Radio’s Car Talk, get stiffed by the Donald when he reneges on his pledge to pay for the building of his luxury castle, Trump Tower North (aka Valhalla), with the hand of his daughter, Ivanka (i.e., Freia).

As he tries to wiggle his way out of this very raw deal, Donald/Wotan manages to make some flimsy excuses to his whining wife Melania (Fricka) for why he needed to build Trump Tower in the first place. He then turns to his shrewd adviser, Newt Gingrich (Loge), who he relies on to come up with a viable solution to this mess. Newt, for his part, suggests they seek out the stingy Sheldon Adelson (Alberich?), the only one of a group of illegal immigrants, known as “dwarfs,” who has enough gold and wealth (not to mention a very potent Ring) to salvage the situation.

If Trump were to take possession of the Ring, fashioned from the gold that three quite enticing Miss Universe contestants in swim suits (the Rhine Maidens) had been carelessly guarding over there by the East River, then all would be well — uh, kinda, sorta.

You get the picture.

This outrageous outline, as ludicrous and hard to fathom as it might sound, has definite stage possibilities, considering how unbelievably complicated and theatrical our national politics have gotten of late.

(End of Part One)

To be continued…

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes