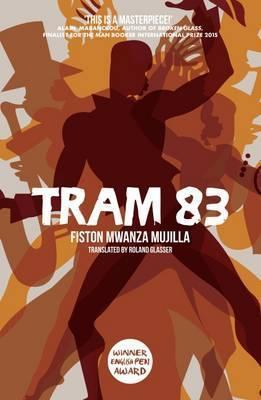

Tram 83, by Fiston Mwanza Mujila and translated by Roland Glasser

There’s a tendency in the UK to expect a certain kind of book from Africa. It’s a serious book, dealing with the pain of a continent and the aftermath of Colonialism. It’s hailed as an important book, but it’s possibly a little dull and hardly anyone reads it. I don’t read it.

At one point in Tram 83 a publisher says to a young author:

We’ve already had enough of squalor, poverty, syphilis, and violence in African literature. Look around us. There are beautiful girls, good-looking men, Brazza Beer, good music. Doesn’t all that inspire you? I’m concerned for the future of African literature in general. The main character in the African novel is always single, neurotic, perverse, depressive, childless, homeless, and overburdened with debt. Here, we live, we fuck, we’re happy. There needs to be fucking in African literature too!”

Tram 83 puts the fucking back into African literature.

Tram 83 is the legendary nightclub at the heart of a breakaway city-state ruled by a dissident general rumoured to be a sorcerer. It’s where everyone goes and everything and anything happens. Well, anything save a quiet conversation.

“Do you have the time?”

Requiem is a local fixer and money-maker. It’s hard to say exactly what he does, but he makes money doing it. His old friend Lucien, a writer, comes to stay with him. Lucien wants to write a doorstep novel featuring twenty famous historical characters from Europe and beyond. It sounds unreadable, but his bigger problem is that he’s finding it unwriteable and Tram 83’s distractions don’t help.

“Call me Astrid. I can’t live without caresses.”

Tram 83 doesn’t have a plot as such. Instead it has sequences of incantatory prose that seems as drunk on Brazza beer and hot jazz as are the regulars at Tram 83. Requiem wants to make money, possibly by robbing a mine (it’s a popular way to make some cash in the mineral-rich city-state, but a dangerous one). Lucien wants to write his book and meets a local publisher who’s interested provided he cuts the number of characters in half, relocates it to South America and perhaps turns it into a play.

“What are you trying to do? Get me horny?”

Requiem and Lucien careen through the city, interrupted constantly by the baby-chicks and single-mamas selling themselves with the constant code-question “do you have the time?” Hardly anybody does. When you’re young you sell yourself, when you’re old you sell whatever you can find. Tram 83 is a merciless place.

“Getting drunk on wine feels like a con. Two little glasses and you lose your head. Beer, now that’s a heavenly way to get wasted.”

Tram 83 is awash with foreign workers and “for-profit tourists”. The Europeans, Americans, Russians, Canadians, now the Chinese all eager to get their own little slice of mineral wealth. Are Requiem and his crew so different? There’s money literally lying in the ground. The foreigners have government contracts while Requiem has to sneak into the mines under cover of night, but the government’s just another set of strongmen, the General a man with more guns on his side than Requiem has. What you get is what you can grasp, and why should Requiem have any less than the next guy?

It was said that in a single day dozens of sacks of heterogenite were carted off from huts and other makeshift camps. With such eroded, tampered foundations, houses threatened to collapse at the slightest rain. Will you consent to starve to death when there’s silver, copper, barium, tin, or coal lying quietly under your feet? From the area around Hope Mine to as far as the east side of Vampiretown, the city took on the appearance of an archaeological site. Even the goats and wheelbarrows smelled of the cobalt quarries.

Meanwhile Lucien tries to make art. He shuns the advances of the baby-chicks, which confuses and offends them. He ignores the pleas from his French publisher for the overdue manuscript he owes, ashamed to admit that he was forced to burn it with a kalashnikov to the back of his neck. He does a reading at Tram 83, the crowd mob him and beat him to a pulp. As the text reflects:

There are cities which don’t need literature: they are literature. They file past, chest thrust out, head on their shoulders. They are proud and full of confidence despite the garbage bags they cart around. The City-State, an example among so many others—she pulsated with literature.

It’s a confident and persuasive paragraph, but perhaps illustrates one problem with the book. In the comments under David Hebblethwaite’s review (links at the bottom) Grant of 1st reading referenced that paragraph noting that while it sounds clever it’s not clear what it actually means. I think that’s fair. The best way to read Tram 83 is to let it wash over you, to treat it like the jazz constantly played at Tram 83 itself. It’s impressionistic, but cumulatively so and if you poke at individual elements they might not hold together quite as well as you’d think.

“I don’t like foreplay. It kills the pleasure.”

Tram 83 is ultimately a hymn to language as much as anything else. It’s no surprise to learn that Mujila is also a poet, because the book hums with poetry. I had several possible one-liner titles for this post. I considered calling this post ‘the monologues of a Kalashnikov,’ which I thought an extraordinarily evocative phrase (though I couldn’t say of what exactly). There are moments of syncopated alliteration like ‘He stepped over the sleepers stretched out on the sidewalk’ and lines that could have stepped out of a William Gibson novel like ‘The Tram retained its botched-night splendor.’

“Give me a real cuddle.”

At times it’s very funny. The exchanges between Lucien and his potential publisher are a micro-satire on the self-importance of literature and the constant tension between art and business in publishing. Lucien clearly has talent, but does anybody care? Abroad, back in France, they do but only for so long as expat African fiction remains fashionable. Back at home nobody’s lining up to buy the latest novel (a theme in Teju Cole’s Every Day is for the Thief also).

“Take me to Bratislava and make me your dream queen!”

It would be easy to make all this bleak and angry. Foreign exploitation, political failure, violence and indifference to anything beyond surviving the next day, it’s potentially grim stuff. What makes Tram 83 different is the sense that regardless of all of this people still meet friends, go dancing, have sex, have a laugh, drink some beers, live. It’s the life as well as the language that makes Tram 83 sing.

Tram 83 knows what it’s doing. There’s clever use of repeated imagery, like the central motif of the never quite finished and war scarred rusting train station. It’s constantly referred to, a landmark both the text and the city revolve around (like the club itself), and as it gets mentioned again and again the description shortens until it becomes simply “the station whose metal structure” with no end to the description at all because none is needed – everyone including the reader knows the station by now and it’s enough merely to refer to it for the rest of its damaged history to spill forth. There’s paragraphs like beat poetry, cascading on for a page or more until you near-drown in the words, coming choking up for air on the other side:

Jalopies out of gas, deep-frozen products from the Galapagos Islands, knick-knacks, ceiling fans, oil changes, sheep, sarcastic remarks, hearses on alert, eggs contaminated with melamine, relics, minarets as far as the eye can see, bistros, baker-deli-linen-fish-lumber stores, phone booths, internet cafés, criminal records, pools of stagnant water, garbage bags at the mercy of beggars, stray dogs, no-entry signs, mountains of refuse, black market in the merchandise and its derivatives, discotheques, abandoned locomotives, born-again Christian evangelist churches, cockfights, settlings of scores, boxing galas, mosquitoes resistant to all pesticides, booing, trolleys, wimps bankrolled by mercenaries, Neanderthals, laundries, desires, beverages, arranged widowhoods of wives of soldiers declared missing, ringworms, jeers revised and corrected by the foreign press, daydreams of dissident rebels prepared to open another front because of an oilfield, magic potions to treat unidentified diseases, backwash and backwash, cannibals, bleeders, baby chicks with their “do you have the time?”, idols with feet of clay, smoking rooms, palimpsests, cathedrals, repeat offenders in custody released on bail who return to the scene of the crime with the weapon of the crime, oriental tapestries, suicidals, the comings and goings of naked-men diddlers, assorted gaffes, superfluities, prolegomena, dark looks, erections paraphrased and channeled into paper tissues…The night came on with her swimsuits and undershirts she forgot to wring out.

I’m more sympathetic to poet-novelists than some, and this is definitely a poet-novelist’s work. In that I was reminded slightly of Jean-Euphèle Milcé’s Alphabet of the Night, against which I commented that where there was a choice between sense and imagery that imagery won every time. That’s true here too. Mujila’s angel-headed hipsters aren’t strictly speaking credible characters. They’re convincing though, provided you go with the flow and don’t poke too hard at what any individual paragraph means exactly.

Tram 83 has the exuberance of late-night live jazz, sending you home blinking into daylight exhilarated and exhausted. It doesn’t play to easy narratives of African experience (as if there could be such a thing in such a vast continent). I didn’t take to it quite as much as I did Mabanckou, those prose-avalanches sometimes smother, but I think it definitely merits the attention it’s received and I look forward to Mujila’s next.

Other reviews

Tram 83 has been pretty heavily reviewed on the blogosphere. David’s Book World’s is here, Tony’s Reading List’s is here, Winston’s Dad’s Blog’s is here, 1st Reading’s Blog’s is here, ANZ LitLover’s Blog’s is here, Words without Borders’ is here and Shiny New Books’ review is here. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn I’d missed some too.

Also potentially of interest is my review here of Alain Mabanckou’s Memoirs of a Porcupine. Mabanckou provides the foreword to Tram 83 and given Mabanckou’s status Mujila can hardly not owe a debt back to him.

The other link with Mabanckou is that I mention above rumours that the dissident general is a sorceror, more specifically the rumor is that he “eats” his enemies in the spirit world just as the porcupine’s master Kibandi does in Memoirs. It’s not a major plot point here (it’s a single throw-away reference), but it’s a nice reward for my having chosen to read several African novels in relatively quick succession so letting me recognize links and common references one to the other.

Filed under: African Literature, Congolese Literature Tagged: Fiston Mwanza Mujila