By Anton

We don’t want to impose our solutions by force, we want to create a democratic space. We don’t see armed struggle in the classic sense of previous guerrilla wars, that is as the only way and the only all-powerful truth around which everything is organized. In a war, the decisive thing is not the military confrontation but the politics at stake in the confrontation. We didn’t go to war to kill or be killed. We went to war in order to be heard.

Subcomandante Marcos

This is a quote from the spokesperson of the EZLN- The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional).

I will refer to them as either the Zapatistas or the EZLN in this article.

Let us begin

History

The Zapatistas went public on January 1, 1994, the day when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. On that day, they issued their First Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle and their Revolutionary Laws. The declaration was that of war on the Mexican government, which was so out of touch with those it was meant to govern, that the Zapatistas declared it illegitimate.

Their original goal was to instigate a revolution in all of Mexico, but as this failed, they used their uprising as a platform to call the world’s attention to their movement to protest the signing of NAFTA, which the EZLN believed would increase the gap between rich and poor people in Chiapas (southern Mexico, where the Zapatistas are based) – one that has sadly become true.

On the morning of January 1, 1994, an estimated 3,000 armed Zapatista insurgents seized towns and cities in Chiapas, including Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Huixtán, Oxchuc, Rancho Nuevo, Altamirano, and Chanal. They freed the prisoners in the jail of San Cristóbal de las Casas, and torched several police buildings and military barracks in the area. The guerrillas enjoyed brief success, but the next day Mexican army forces counter-attacked and fierce fighting broke out in and around the market of Ocosingo. The Zapatista forces took heavy casualties, and retreated from the city into the surrounding jungle.

This is where the strategy changed.

Due to the failure of the Mexican Government to capture the Comandantes of the EZLN, they took up a policy of negotiation.

The Zapatistas changed tactics to mobilisation and a media campaign through numerous newspaper comunicados.

On June 28, 2005, the Zapatistas presented the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, declaring their principles and vision for Mexico and the world. This declaration reiterates the support for the indigenous peoples, who comprise roughly one third of the population of the state of Chiapas, and extends the cause to include “all the exploited and dispossessed of Mexico”. It also expresses the movement’s sympathy to the international alter-globalization movement, and offers to provide material aid to those in Cuba, Bolivia, Ecuador and elsewhere, with whom they make common cause. The declaration ends with an exhortation for all who have more respect for humanity than for money to join with the Zapatistas in the struggle for social justice both in Mexico and abroad. The declaration called for an alternative national campaign (the “Other Campaign”) as an alternative to the presidential campaign. In preparation for this alternative campaign, the Zapatistas invited to their territory over 600 national leftist organizations, indigenous groups and non-governmental organizations in order to listen to their claims for human rights in a series of biweekly meetings that culminated in a plenary meeting on September 16, the day Mexico celebrates its independence from Spain.

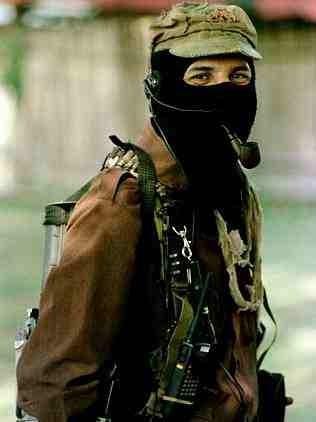

The most recent campaign was when the Zapatistas marched through the streets on the 22nd of December, one day after the start of the new Mayan calendar. They marched, all in balaclavas, in complete silence.

Ideology

The Zapatistas have an ideology that can only be described as libertarian socialism. The Zapatista slogan is that of mutual aid, formulated by Peter Kropotkin, the ‘inventor’ of anarchist communism:

“For everyone, everything. For us, nothing” (Para todos todo, para nosotros nada).

The EZLN opposes economic globalization, arguing that it severely and negatively affects the peasant way of life of its indigenous support base and oppressed people worldwide.

The Zapatista controlled areas are ran on a bottom-up democracy system, similar to soviet democracy, limiting public servants’ terms to only two weeks, not using visible organization leaders, and constantly referring to the people they are governing for major decisions, strategies and conceptual visions.

“my real commander is the people”

Subcomandante Marcos

Unlike other ‘revolutionary’ movements like FARC and shining path, the EZLN, before their uprising in 1994 explicitly defined a right of the people to resist any unjust actions of the EZLN. They also defined a right of the people to:

demand that the revolutionary armed forces not intervene in matters of civil order or the disposition of capital relating to agriculture, commerce, finances, and industry, as these are the exclusive domain of the civil authorities, elected freely and democratically.

“The people should acquire and possess arms to defend their persons, families and property, according to the laws of disposition of capital of farms, commerce, finance and industry, against the armed attacks committed by the revolutionary forces or those of the government.”

Subcomandante Marcos

The following information comes from the documentary ‘a place called Chiapas’

As a young man, Subcommander Marcos was politically radicalized by the Tlatelolco massacre (2 October 1968) of students and civilians by the Mexican federal government; consequently, he became a militant in the Maoist National Liberation Forces. In 1983, he went to the mountains of Chiapas to convince the poor, indigenous Maya population to organize and launch a proletarian revolution against the Mexican bourgeoisie and the federal government. After hearing his proposition, the Chiapanecs “just stared at him”, and replied that they were not urban workers, that, from their perspective, the land was not property, but the heart of the communities.

Imagine a person who comes from an urban culture. One of the world’s biggest cities, with a university education, accustomed to city life. It’s like landing on another planet. The language, the surroundings are new. You’re seen as an alien from outer space. Everything tells you: “Leave. This is a mistake. You don’t belong in this place”; and it’s said in a foreign tongue. But they let you know, the people, the way they act; the weather, the way it rains; the sunshine; the earth, the way it turns to mud; the diseases; the insects; homesickness. You’re being told. “You don’t belong here”. If that’s not a nightmare, what is?

Marcos’ political philosophy is often characterized as Marxist and his populist writing, which concentrates on unjust treatment of people by both business and the State, underlines some of the commonalities the Zapatista ideology shares with Libertarian Socialism and Anarchism.

When asked about whether he is worried about the risk of assassination, he relied with this:

“We don’t fear to die struggling. The good word has already been planted in fertile soil. This fertile soil is in the heart of all of you, and it is there that Zapatista dignity flourishes.”

You can find many interviews with Marcos on you tube. I recommend checking them out.