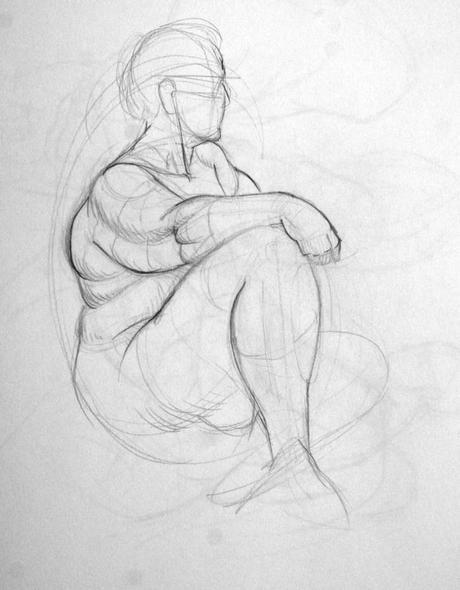

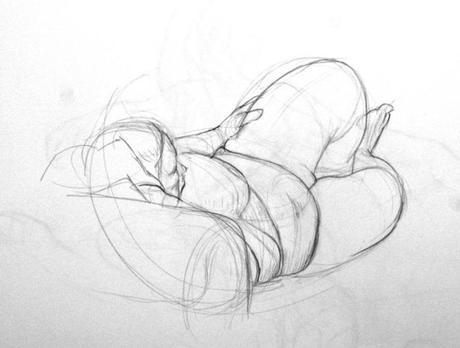

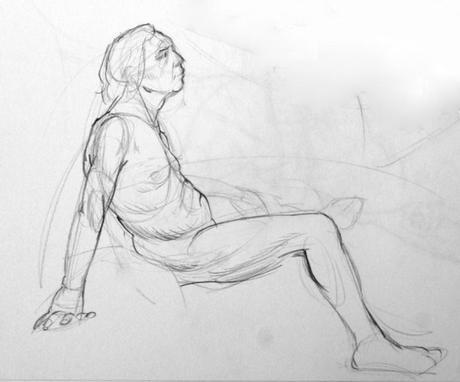

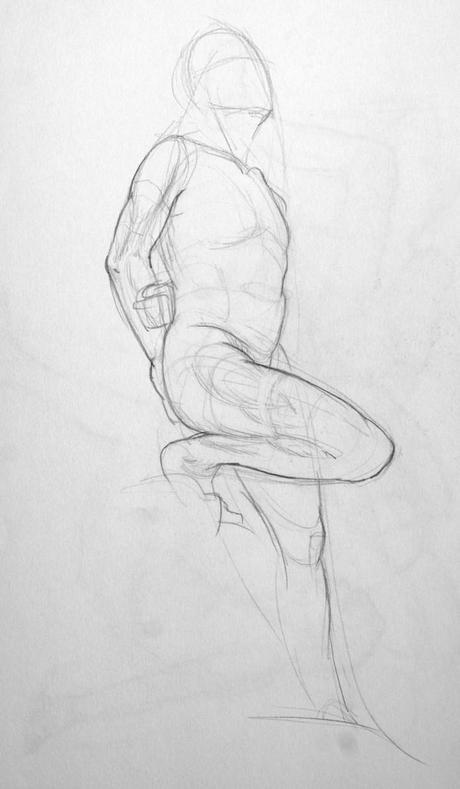

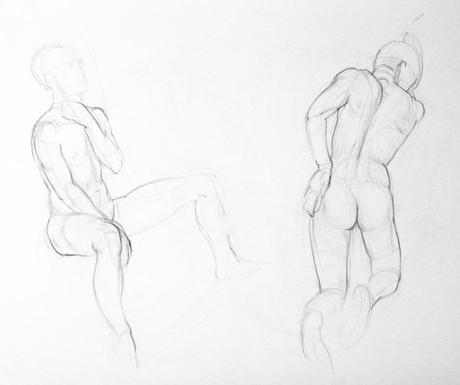

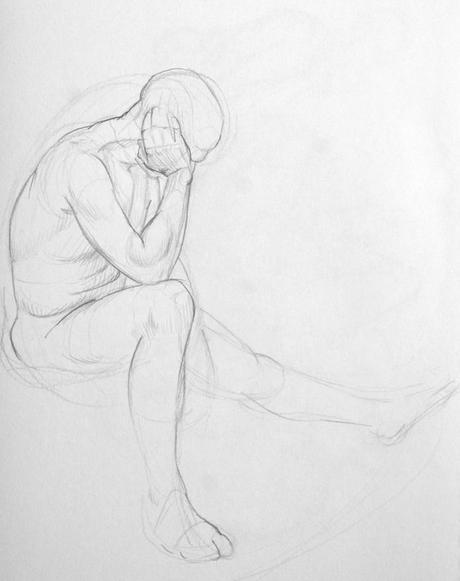

I’ve happened upon one of the best sketch clubs I’ve ever had the good fortune to attend in tough and vibrant Glasgow, tucked away behind an inconspicuous back door in a dive bar perched on the outer skirts of the city center. All the Young Nudes will be pleased to apply deafening and achingly cool music to your ears and drown out all other tedious distractions or heckling of the (three) models, while giving you the choice of shorter or longer poses depending where you station yourself, and of course you have access to beer on tap. Best of all, the models really are nude, something I’m finding a bit of a luxury of late in costume-oriented groups, allowing me to learn about the body once again.

Of course, not everyone seems to attend sketch clubs in order to learn about the body. Which makes me wonder why people demand the luxury of a nude in their midst. I’ve found myself unhappily seated beside grown men with greying hair solemnly applying crayons to their paper in a decisive scribble with no correlation to the figure before them, before ceremoniously smearing the pathetic mess in turpentine. Or others who spend as much time invoking magic as they do drawing, waving their hands in spell-casting fashion at the long-suffering model. I pick on the old men because they have no excuse for not being able to draw by now, and worse—they generally feel compelled to offer us younger punters unsolicited instruction.

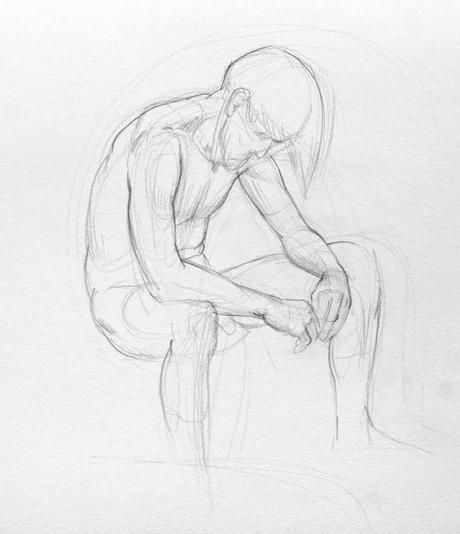

I firmly believe that many of my contemporaries have no inkling of what the life class is. Each new pose, in their eyes, offers the opportunity for a new piece of Art. Another chance for the deity of Inspiration to channel something mind-blowing through their pencil. Each attempt is an end in itself. But the life class is simply about hard work, observation and practice. If anatomy is irrelevant, perhaps you’d do better to draw trees. Trees have limbs, too, and sit really still, and I’m sure would inspire similar profusions of confused chalky expression. It’s much cheaper.

An aimless girl I met at said group confessed she has no knack for hard work, and would rather not put time and effort into drawing. Better to show up once a week, get drunk, and see what happens. She boasted that she was surprised by her own output, especially since it was so consistent. I had asked for no defence of her work, mind, but she was eager to explain to me why my ‘academic’ studies were no more valid than her half-arsed efforts. Consistency is the key, she forged on, for consistency is what she most values in art. If an artist is consistent, then they have a style, and style takes pre-eminence above all facility. What madness that an image can’t stand on its own merit, but requires a context to support it! I began to wonder if this preoccupation with ‘style’ is what drives the insistence on solo exhibitions.

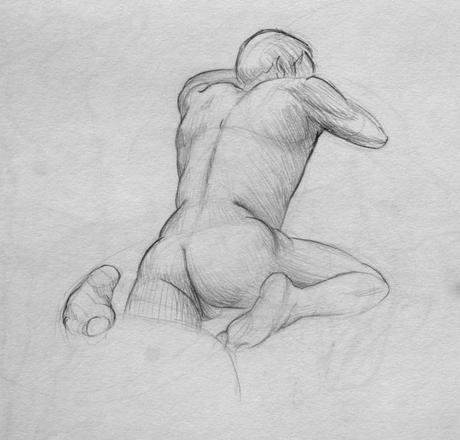

My contemporaries find my ‘style’ very easy to categorise as straight-up academic. ‘Oh, you draw in an academic style, I see,’ is the disappointed summation of my studies, which, don’t forget, I execute for my own studious purposes, not as works of Art. Others are more flattering: ‘You draw like a sculptor.’ Or, ‘You draw like an animator.’ Sculptors and animators are people who have an understanding of three-dimensional form and motion, of the construction and machinations of the body, and I feel more at home in such company. Oddly, I’m never told, ‘You draw like an artist.’ For artists can’t really draw, can they?

Nor are they required to—and this is a significant obstacle. As Gombrich (1972: 13) lucidly explains in his fabulously unpretentious book The story of art, art was always produced toward some end: ‘Most of the paintings and statues which are now strung up along the walls of our museums and galleries were not meant to be displayed as Art. They were made for a definite occasion and a definite purpose which were in the artist’s mind when he set to work.’ Endless fretting about originality and expression never clouded the visage of the artists of the distant past. And yet, argues Gombrich (1972: 119), ‘there remained enough scope for him to show whether he was a master or a bungler.’ The unmasked utility of his work did not necessarily constrain him.

For to be an artist is to be in the possession of a creative and problem-solving mind, and to have the urge to turn this mind towards tasks and problems and devise wholly new configurations. We are inventive creatures, our mental flights stray from the worn paths; our specialty is to approach things in ways that have not yet been considered. And as painters and sculptors we do this in a very physical, sight-dependent way, merging thought with touch.

What we demand, then, are tasks! Ritual masks, cathedrals, portraits, book illustrations (Gombrich, 1972: 473)! Gombrich (1972: 472-3) compares these tasks to the grit around which a pearl can form. ‘If the artist’s feelings for forms and colours are to crystallise in a perfect work,’ he argues, ‘he, too, needs such a hard core—a definite task on which he can bring his gifts to bear.’ The cause is, just quietly, of little concern to the artist, whose problem-solving mind whirs over solving the physical task at hand rather than elusive concepts of beauty and expression (1972: 13). And that’s where her abilities come into their own: ‘The pearl completely covers the core. It is the secret of the artist that he does his work so superlatively well that we all but forget to ask what his work was supposed to be, for sheer admiration of the way he did it’ (1972: 473).

Gombrich’s book fluidly traces a cultural history in which communities set definite tasks for artists, who, endlessly in need of challenge, performed them with great ingenuity and finesse. Yet there came a point when artists were forced to turn inwards for such challenges. Says Gombrich (1972: 473) sombrely: ‘It was a fateful moment in the Story of Art when people’s attention became so riveted on the way in which artists had developed painting or sculpture into a fine art that they forgot to give artists more definite tasks.’ With attention now firmly fixed on what these inventors would invent next, a string of ‘isms’ succeeded the artists’ own attempts to set themselves puzzles about light, form and colour, but also about meaning.

Celebrated Glaswegian writer and artist Alasdair Gray (2007: 306-7) perfectly captures this claim in an increasingly impassioned dialog between art student Duncan Thaw and his fellow hospital inmate, a local minister, in his spectacular novel Lanark:

‘There are very few good jobs for handworkers nowadays,’ said Thaw, ‘so most parents and teachers discourage that kind of talent.’

‘Did your parents encourage you?’

‘No. They allowed me paper and pencil when I was an infant, but apart from that they wanted me to do well in life.’

…

‘Tell me, just to change the subject, why are modern paintings so hard to understand?’

‘As nobody employs us nowadays we’ve to invent our own reasons for painting. I admit art is in a bad way. Never mind, we’ve some good films. So much money has been put into the film industry that a few worthwhile talents have got work there.’

The minister said slyly, ‘I thought artists didn’t work for money.’

Thaw said nothing. The minister said, ‘I thought they toiled in garrets till they starved or went mad, then their work was discovered and sold for thousands of pounds.’

‘There was once a building boom,’ said Thaw, growing excited, ‘In north Italy. The local governments and bankers of three or four towns, towns the size of Paisley, put so much wealth and thought into decorating public buildings that half Europe’s greatest painters were bred there in a single century. These bosses weren’t unselfish men, no, no. They knew they could only win votes and stay popular by giving spare wealth to their neighbours in the form of fine streets, halls, towers and cathedrals. So the towns became beautiful and famous and have been a joy to visit ever since. But today our bosses don’t live among the folk they employ. They invest surplus profits in scientific research. Public buildings have become straight engineering jobs, our cities get uglier and uglier and our best paintings look like screams of pain. No wonder! The few who buy them, buy them like diamonds or rare postage stamps, as a form of non-taxable banking.’

Thaw’s claims ring as clear as ever in our own time. Inhabited public places comprise almost exclusively places of commerce: retail and dining. They are fashioned as such, and designed to urge consumption and to foster endless want and desire. Many of our cleverest and most innovative problem-solvers are more likely than ever to find their abilities at the disposal of advertising, which must be produced quickly, must be sharp and forceful, and is by nature throw-away. I’m not sure whether to be grateful to those who see value in and reward creative skills, employing us once again as humble handworkers, or whether to despair at the sorry ends to which such hands and minds have become servile. At any rate, a seemingly insurmountable division has grown between ‘commercial artists’ and ‘fine artists,’ with the latter largely unwilling to accept such tasks. Something more is demanded.

Gombrich expertly laces together a preoccupation with style and the lack of suitable tasks. ‘Ever since artists had become self-conscious about ‘style’ they felt distrustful of conventions and impatient of mere skill,’ he writes (p. 439), continuing, ‘They longed for an art which did not consist of tricks which can be learned, for a style which was no mere style, but something strong and powerful like human passion.’ In not being required to produce anything specific, art itself became the task: the puzzles became more and more esoteric the less they became about applying art to external problems. Style is what remains when other goals are removed from the picture. Of course, that doesn’t defend laziness or ineptitude, as the indomitable draughtsman Pietro Annigoni fiercely wrote:

The truth is that the deformations of contemporary painters very seldom arise from stylistic requirements forced on the artist by his vision. They merely spring from a confused desire to be controversial, a surprising indifference to the human being and, one might add, a lukewarm commitment to life itself. The result is absolute indifference to form, lack of proper preparation and a heavy dose of sheer ineptitude. This last quality has today, it seems, acquired full rights of citizenship in the realm of art.

The less fiery Gombrich (p. 474) leaves us with this rebuke: ‘There are certainly painters and sculptors alive today who would have done honor to any age. If we do not ask them to do anything in particular, what right have we to blame them if their work appears to be obscure and aimless?’ I firmly believe we must forge a new chapter in the ‘story of art’ and that obsession with style over ability, along with the solo show and its narcissistic introspection, ought to be abandoned. Perhaps finding the modern task-giver will be crucial to this project.

Gombrich, E. H. 1972 [1950]. The story of art, twelfth edition. Phaidon: Oxford.

Gray, Alasdair. 2007 [1969, 1981] Lanark. Canongate: Edinburgh.