The chariot race from William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959)

The chariot race from William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959)Row, Row, Row Your Boat

What adventures await Judah Ben-Hur! When last we left him, Judah had been condemned to a living death as a slave aboard a Roman warship. For three years he nursed his revenge, waiting for the day when he could mete out justice to former boyhood friend Messala, the man who falsely accused him of trying to kill the new Roman governor of Judea. What was it that kept Judah focused during those harsh times? Was it the life-giving water? Was it Christ’s tender touch? Was it Judah’s renewed faith in his fellow man? Hardly!

When the hardened Roman commander Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins) comes upon Judah for the first time, he decides to test his resolve. Flinging a flesh-ripping whip across Judah’s back, Arrius is impressed with his ability to restrain himself. “You have the spirit to fight back, but the good sense to control it.” He notices the angry flame that courses through Judah’s veins: “Your eyes are full of hate, forty-one. That’s good. Hate keeps a man alive. It gives him strength.”

Hate is what will dominate Judah’s life for the remainder of the picture. However, it’s the degree to which he uses that hate that will allow him to overcome the challenges he still needs to face. Arrius perfectly summarizes Judah’s situation, and those of his fellow galley slaves, by imparting the following advice: “Now listen to me, all of you. You are all condemned men. We keep you alive to serve this ship. So row well … and live.”

Through a strange quirk of fate (or act of God, if you prefer), Judah Ben-Hur saves the Roman commander’s life. As a reward for his action, Arrius takes him to Rome to train as a charioteer. Then, over the years, he adopts Judah as a son and legal heir to his wealth and property. But the grateful Judah has other plans. He returns to Judea to search for his mother Miriam (Martha Scott) and sister Tirzah (Cathy O’Donnell), as well as fulfill his oath to seek retribution against the detestable Messala.

Most viewers and critics agree that the fabled chariot race is the high point of this epic story. Taking nothing away from one of the all-time most thrilling action sequences ever filmed (staged by second unit director Andrew Marton), the chariot race climaxes with Judah’s victory in the Circus Maximus and Messala’s brutal demise.

But prior to the tribune’s passing, Messala makes him aware that his mother and sister did not perish, as Judah had previously thought. In fact, they are very much alive, if that’s what you call it. “Look for them,” he blurts out viciously, “in the Valley of the Lepers … if you can recognize them. It goes on, Judah … it goes on … The race … is not over.”

If Judah had not been radicalized before this point, he most certainly would be now — and more than willing to take up arms against his Roman oppressors.

The Way of the Cross

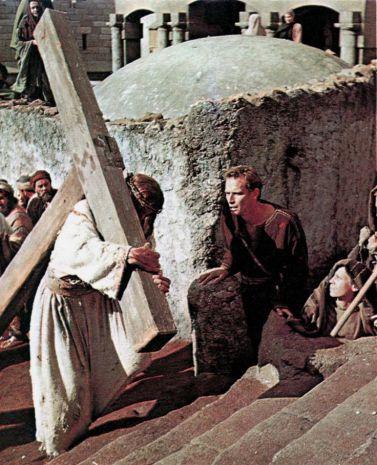

From the spectacle of the Circus Maximus we move on to the public trial and personal turmoil of Christ at the Crucifixion. Roman Governor Pontius Pilate (Frank Thring) is washing his hands of the matter. We see Jesus in long shot, moving from the center of the film frame to the right.

Similarly, we cut to Judah entering, also from mid-center. He carries his sister Tirzah, who along with his mother have contracted leprosy after their time in prison. Roman soldiers on horseback mount the steps which will take them to the scene of the Crucifixion. Next, Jesus is perceived, again in long shot, as he carries his cross. Cut back to Judah at left with Esther (Haya Harareet), the woman he has fallen in love with, and Judah’s mother and sister.

In the next scene, they are all gathered near the steps that lead to a public square. The shadow of Christ’s cross appears against a stone wall — the wall that separates man from God; from the Creator of all things (as He was pictured at the start of the picture) and from those who have turned their backs on His only begotten son, the Savior of the world. Christ has taken on man’s sins in this moving episode.

There is a quick cut to Judah at center frame, his chiseled features facing right. Judah’s words cut to the bone: “I know this man!” he confides in a voice wracked with astonishment. The camera moves over to the three women, Tirzah at left on the lowest level of the steps, Miriam in the center position (both with faces covered by their wraps), and Esther at middle right, her own face a study in disbelief at what is being done to this humble carpenter before them. Her arms are placed on the stone steps in support of her weight. Esther is powerless to help the poor wretch who carries his own cross. Christ’s shadow momentarily falls on her face as he staggers by.

In the next instant, Christ stumbles (the first of several falls). The soldiers respond by whipping him into submission. Judah moves in to assist the fallen Jesus. Interestingly, the cross’s beam intersects the film’s frame; it looms larger than any of the women present, or Ben-Hur for that matter. The Roman soldiers also traverse the frame, larger than life and just as threatening. At the soldiers’ crack of the whip, Tirzah cries out, “Easy on him!” But her cry gets no response. Jesus continues the long trek up the steps to his eventual death.

The camera pans to the other bystanders bearing witness to this painful display, Christ’s Via Crucis. Some of the onlookers express remorse and dismay; others mock the forsaken victim, while still others can only watch, emotionless and uncomprehending as to the momentous events taking shape before them.

The camera movement continues, panning to the right, following the crowd as they move forward, ever forward. The camera then cuts to Christ’s footsteps. They are heavy and beleaguered by the burden of carrying the enormous wooden cross. The object’s heaviest section scrapes against the stone masonry as he slowly inches his way upward and onward. The music intones a mournful theme.

At that moment, Jesus stumbles anew. His left arm, bloodied and battered from the beating he received from the scornful Roman soldiers, prevents him from falling altogether. Sensing the urgency of the situation, Judah takes off his robe and charges Esther with watching over his family. He resolves to follow the crowd up the steps in pursuit of the figure, the man he claimed to “know,” but from where? Under what circumstances could he have met such a pitiable creature as this?

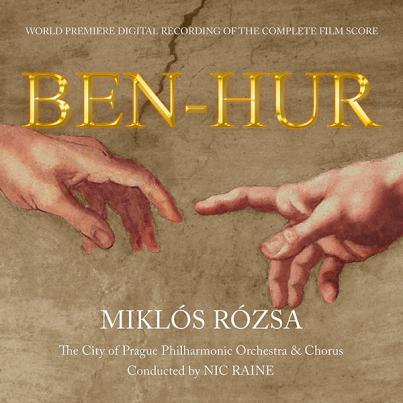

Judah pushes his way through the armed guard, his movements going from left to center, and from center to right — just as it was in the desert sequence earlier on (see the following link to my earlier description of this scene, i.e. the “Walk of Life”: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2014/10/25/the-view-from-the-chair-walk-of-life-an-analysis-of-two-scenes-from-william-wylers-ben-hur-1959-scene-one-the-water-of-life/). Here, in the “Procession to Calvary” sequence, that doleful theme music (by composer Miklós Rózsa) becomes, in actuality, a minor-key inversion of the manly four-note “Ben-Hur” motif heard at the beginning of and throughout the drama. It implies that Jesus and Judah’s situations have been reversed.

The women depart towards the center of the frame. They can no longer be of any assistance. Esther berates herself for dragging Tirzah and Miriam to witness such a tragedy. But Miriam is more accommodating. “You haven’t failed,” she comforts her. It’s not Esther’s fault that men have treated each other so cruelly. Why, look at Judah and Messala. Once they were bosom companions, as close as brothers, sharing an unbroken bond of fealty and love. Then, they turned on one another: Messala for needing Judah’s help in fingering the Jewish resistance leaders; and Judah for refusing to betray his own people. Their clash was over politics and religion, ideology over practicality.

The Center of Attention

We come to the center of the square. One observer shouts, with his hand raised mockingly in the air, “Hail, King of the Jews!” Between the crosses of the other two prisoners we can spot Judah, still mingling with the crowd, looking for an opportunity to come to this man’s aid. Why? What does Judah owe this miserable human being? He keeps moving forward, as Christ, who is at the extreme left of the screen, also does.

It’s at this point that Jesus’ burden begins to take a toll on his broken body. He stumbles badly, with the cross falling directly on top of him. He is on the ground, his arms splayed in a posture that will be replicated at the Crucifixion, except with him hanging from this same cross. Judah is finally able to break through the crowd. He’s about to reach the fallen victim when a foot soldier sideswipes him back into the crowd. Judah crashes into a well (which resembles an ancient water trough).

Meanwhile, one of the soldiers coaxes a passerby — Simon the Cyrene — into carrying Jesus’ cross so that the procession can continue on its dolorous way. As Christ struggles to get back to his feet, Judah quickly snatches a ladle and, filling it with fresh water, tries to deliver its contents. They are both in the exact center of the screen: Christ positioned at center-left and Judah at center-right; a complete turnaround from their previous encounter where Judah was in Christ’s position on the ground and Christ came to his rescue from the right.

As Judah bends down to offer him a thirst-quenching drink, he suddenly remembers their former meeting. The expression on Judah’s face changes from compassion to utter shock and recognition. How their situations have so changed; how their circumstances over the years have conspired to reverse their separate fortunes. Just as Jesus is about to drink, a soldier interrupts their reunion (without the need for the phrase, “No water for him!”) by kicking the ladle from Judah’s outstretched hands, thus spilling the refreshment onto the street.

Throughout this continuous sequence, director William Wyler has positioned both Judah and Jesus in long view, that is, until the camera crouches down to eye level, just as the two men confront each other in close up. Intruding on the pair, the soldiers manhandle Judah out the way. Both stumble to the ground, the symbolism here being unmistakable: each has stooped so low in life — Judah, a prince of his people, turned a slave aboard a Roman galley, now restored to his former station; Jesus, a simple carpenter’s son, hailed as the long-awaited Messiah, now about to be crucified between two criminals.

From this personal abyss, there comes a reaffirmation. In Christ’s case, his death and glorious resurrection; in Judah’s, a reassessment of his life, one dedicated to family and charity toward others. Deprived of the merest hint of sustenance (the screenplay ignores Christ’s injunction to his disciples at the Last Supper: that he would not eat or drink until his task was complete), Jesus marches wearily to his fate.

Similarly, Judah stands at the center of the storm. As he did in the earlier sequence, Judah rises to his full height at far left — the opposite of where Christ Jesus had stood upon quenching Judah’s thirst. In Judah’s right hand we see that he holds the ladle, emblematic of the one that revived him the last time the two men had met. Their positions are mirror images of where they once stood so many years before. Only here, Jesus does not look back, as Judah had done. Christ has left his past behind. He can only march solemnly ahead.

The sequence ends with the shadow of a Roman soldier cast across Judah’s backside. Two soldiers enter the frame, each on opposite ends of the frame, wearing flowing red capes (the blood of Christ on their shoulders?). Judah is obstructed from view, whereas Jesus is dressed all in white; he remains visible at the center, the image getting progressively smaller and smaller with each step, trudging incessantly to his death.

The next scene takes us to Calvary; a short while later, Christ is no more. A terrible rainstorm breaks out, but in a cave nearby a miracle has occurred: Tirzah and Miriam are cured of their leprosy. Esther is overjoyed. Rain begins to fall. We switch back to the cross where Christ’s limp body hangs. His blood flows down from the cross to a stream below. The stream then becomes a raging torrent, as Christ’s blood, mixed with the water and rain, washes man’s sins away.

In the final scene, Judah returns to his ancestral home. He confesses to an expectant Esther that Jesus’ last words were of forgiveness for mankind. Those same words, a comfort in our own hard times, took the sword of vengeance from his hand. A lifetime of rage and hatred has been replaced with absolution and understanding.

Judah is reunited with his newfound family (he marvels at their smoothened complexion). They embrace. The bonds of love and faith have been reaffirmed. In the end, the Christ theme blazes forth, blending with Judah’s theme as well as his and Esther’s love music.

A heavenly choir proclaims the “Alleluia” as a portion of the “Creation of Adam” panel reappears. Only Adam’s hand and God’s life-giving touch are visible, a reaffirmation of the bond that exists between man and his maker.

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements &b; &b;