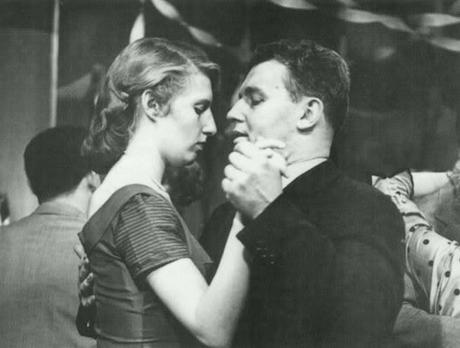

Clara (Nancy Marchand) and Marty (Rod Steiger)

Mama's BoyMarty Pilletti is a butcher, a common enough profession in a common enough working-class world. His sisters and younger brother have all gotten married, but Marty's the lone holdout.

"You should get married," his customers tell him, a common enough expression from people who mean well - one they repeat to themselves, but more often than not directed at good-hearted Marty. Why, he should be ashamed of himself.

"When are you going to get married?" they regularly ask him. It's a question Marty is loath to respond. In all honesty and in view of his profession, it cuts him to the bone.

Marty has a friend, Angie. They commiserate together at the local drug store, or wherever they happen to meet up. He's another one of Marty's pals on the make. Two lonely guys from the Bronx, "losers" if you want to be cruel.

Marty is thirty-six, a fat ugly, little man that girls don't want. He's gotten that description into his head. They have no interest in him, at least that's what Marty believes.

His and Angie's "old ladies" (their mothers, to be precise) ask the same question to them, over and over again: "When are you getting married? When are you getting married" It's enough to drive a guy to drink. Thankfully, Marty's not the type to booze it up. Not yet, we hope.

The loneliness, the insecurity, the self-doubts, the lack of confidence, the looming despair, but most of all the fear of rejection - these are what Marty gets in return. Because of this, he's had to develop a coping mechanism, mainly excuses for not making himself available to go to the movies or the local dance hall.

The Waverly Ballroom on the Grand Concourse, that's the place to be - it's packed to the rafters on Saturday nights. "Loaded with tomatoes," so states Marty's mother, Mrs. Pilletti. Again, it's always the same, his having to face that inevitable query, this time posed by Mama herself: "What you going to do tonight?"

Mama doesn't want him hanging around the house. She's a widow, that's true, but all her children are married - all except "poor" Marty, the oldest. Time for him to be out on his own, or so she thinks.

In as matter of fact a manner as possible, Marty insists to his mother that she has a bachelor on her hands. "I ain't ever going to get married," he declares, as he plops some food on his dinner plate. Whatever girls like he doesn't have it, so guys like him must face the facts. And that's that.

"I've taken enough girls out to enough dance halls," he contends, probably for the hundredth time. "I don't want to get hurt no more. I called up a girl this afternoon and she gave me the brush off. Some 'broad' I didn't even want to call up. I'm past the point of getting hurt."

He confesses his feelings to Mama, hoping against hope that she finally comes around to his point of view. "The place makes me feel like a bug just standing around. I had enough pain, no thank you."

Not taking the hint or, more correctly, not wanting her son to suffer as most loving mothers would assert, Mama calls out to him. But Marty is quick on the draw: "Please, I'm gonna stay home and I'm gonna watch Sid Caesar." Mama does not get it. Instead, she fires back with a hurtful line she knows will get a rise out of her boy. "You gonna die without a son!"

That does it. Marty repeats the line back to her. "I will die without a son!" But Mama will have none of it. Imagine! An American-born Italian descendant from the Bronx, a hard-working butcher at that, unmarried, with no prospects for a decent family life on the horizon. This is anathema to Mama's ears. She has to do something about it - now!

Mama tells him to wear the blue suit, but this only gets Marty more riled up. "The blue suit, the gray suit, I'm a fat, ugly little man!" he shouts, while pounding the dinner table. If it's drama Mama wants, drama she'll get. And, brother, does her oldest son give it back to her. "I'm miserable enough as it is," he cries out. "Whadaya want from me? I'll get heartache, that's what I get. A great big night of heartache."

These are words and arguments he's no doubt expressed countless times before, but never so heartfelt, never so achingly poignant as he's doing so now. Spilling his guts out to Mama probably wasn't in the cards, as his poker pals might call it. But he does it anyway. Shoot, what the heck? What's he got to lose?

Pulling back the pain and realizing he may have gone too far, Marty grasps the fact that he's hurt his mother - and himself, to be honest. Surely, that was never his intention. Gently and calmly, he bends down and kisses her hand. He's at the point of breaking down but manages to control himself just enough to sit back down at the table and finish his meal.

"Oh boy," Marty mumbles to no one in particular, then repeats the line his mother used on him at the start of their conversation: "Loaded with tomatoes... that's rich, Mama."

Heartache Tonight, Heartache TonightDirected by Delbert Mann, written by Paddy Chayefsky, and produced by Fred Coe, along with assistant producer Gordon Duff, the teleplay Marty premiered live on May 24, 1953, on the Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse show.

The program, a made-for-television production, starred Rod Steiger as Marty, and Nancy Marchand as Clara, the girl at the dance hall. Two years later, the independent team of Harold Hecht and actor Burt Lancaster produced the Academy Award-winning film version, which starred Ernest Borgnine (Oscar winner for Best Actor) as Marty, and Betsy Blair (then-wife to Gene Kelly) as Clara.

The movie version was partially filmed in the Bronx, near and around the Grand Concourse and Fordham Road areas, as well as Arthur Avenue and the Belmont neighborhood (across the street from Fordham University where this writer attended and graduated from). This was a section of the Bronx known locally as "Little Italy" and made famous for its restaurants, and the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel.

In the original teleplay, a stocky Rod Steiger, as Marty, captures everyone's hearts with his homespun portrayal. Steiger wears his feelings on his sleeve, so to speak. He can barely hold back the tears in the key scene, described above, with his mother (played by Esther Minciotti, who also appeared in the movie version). Joe Mantell plays Angie, Lee Philips is Marty's married cousin Tommy, and Betsy Palmer his wife Virginia (originally, Anne Bancroft, whose real name was Anne Italiano, proved too "ethnic looking," so for contrast the producers went with Ms. Palmer).

As Chayefsky wrote the part, the butcher Marty is a broken man inside. And this is how Steiger plays him: as outwardly friendly, yet all-but-crying internally. It's an "interior" performance that barely manages to bubble up to the surface; one where Steiger tries mightily to hold back the floodgates as an alternative to releasing those pent up feelings of despair and sorrow with regard to the character's failed romantic relationships.

In rehearsal, both director Mann and producer Coe tried in vain to prevent Steiger from letting it all hang out, but to no avail. Each time he performed that scene, Steiger cried his eyes out, as he was taught to do by way of his Method-actor training. Even at the dress rehearsal, Steiger welled up inside so much that the dam would literally burst open, and tears would pour out in full force.

Mann and Coe could not let that happen. Their take on the matter was that actors make the audience weep, not the performer him- or herself. After all, this was live television. How could they go on with the show when their principal lead had given so much so soon to the little screen?

When the time arrived for the dinner table talk with Minciotti, Steiger came almost to the point of weeping. But instead of breaking down as he had done on prior occasions, he got hold of himself, so that his delivery was chopped up into tiny fragments, the most memorable of which was the now-immortal line, "I'm an ugly man, I'm a fat ugly, little man." It's absolutely devastating, as it was meant to be.

Marty willfully tries to cover up the pain. He's embarrassed or ashamed - and a little of both. In the tiny, round television screens that were prevalent in the early 1950s, Steiger's natural bulk appears to resize itself down to gnome-like proportions, resulting in the large-framed Italian butcher's reduction to a whimpering pile of human flesh. He's comparable to a misbehaving child, left cringing in the corner for some infraction or other.

This timely bit of self-control saved the scene from over-playing its hand, which had the intended effect: audiences around the country cried their hearts out for the fat ugly, little man.

In Ernest Borgnine's movie take, the scene is the same, the lines are the same, but the intimacy that the small screen allowed viewers to experience (specifically via Steiger's reductive approach) were, in the movie theater, broader and larger than life, in the sense that Borgnine was playing to a wider, more varied audience.

It's as if he and Mann had aimed their sites at the topmost gallery; as if the audience were seated in New York's Yankee Stadium, and in the upper bleachers to be exact. Consequently, Borgnine comes off as larger than life, as were his emotional reactions. We have little doubt that Marty Pilletti is indeed a big, fat mama's boy.

Borgnine, because of his size and heft, is more physical as well. And he uses his physicality to good effect - this actor is unafraid to let his gut hang out in full view of the audience. But then, we lose a little something in the interim and in the transfer from one medium (those round-screen television sets previously mentioned) to the larger and wider movie screens.

Still, that improvised scene at the bus stop, where Marty instinctively punches the sign with his fist after a successful night out with the girl, left audiences laughing and crying, both at the same time. That's what good acting is about!

This Operatic LifeBoth Borgnine and Steiger get the brushoff. At the ballroom, a guy walks up to Marty and tries to unload a "dog" on him. This guy has found a "hot chick" and even offers to pay him five bucks if Marty will take the so-called "dog" off his hands. Chivalrous to the end, Marty refuses. "You can't just walk out on a girl like that." Marty's indignant - and rightly so, after having been on the receiving end of rejections for as long as he can remember.

In the teleplay, the girl is tall and big boned, with a prominent proboscis. Disgusted and insulted at being treated like a bargaining chip, the poor girl heads for the exit to cry her eyes out - undoubtedly, a routine matter for her. Does this all sound familiar? With Marty, however, the girl, Clara, gets up the courage to confess to him that this happens every time she comes to the dance hall. He knows exactly how she feels.

Understanding soul that he is, Marty decides to make a confession of his own: "Big-hearted, you get to be a professor of pain." What a masterful line! Two lonely people, out on the dance floor: he's thirty-six, she's twenty-nine, an old maid to most mother's eyes. They dance and talk, spilling their guts out to one another, commiserating in mutual bliss. Two "dogs," together at last. Marty chats about his ugly father who was so kind to his mother and to each other. They dance and talk some more, for what seems an eternity.

Lest the idea be lost on readers, writer Chayefsky, who experienced as much pain and rejection from girls due to his short, stocky build and unconventional nature, has captured on screen and at home the essence of Puccini's La Bohème, with all its heartache and anguish. From their "meet-cute," Marty embodies the poet Rodolfo, a romantic at heart, while Clara is the good-natured Mimì. No, she does not die of tuberculosis as her counterpart does, but then... who knows what life has in store for our lovebirds?

As Clara, Marchand (in the teleplay) uses her imposing height to denote awkwardness, her big-boned features made prominent in comparison to Rod Steiger's softer-edged contours. She's all arms and elbows and angularity, externalizing her manner and gawky bearing whereas Steiger internalizes his thoughts and actions.

Steiger holds back the pain but feels no less deeply; Marchand represents the embodiment of his prior rejections, thereby giving "Marty" a sense of his own painful dismissal by others. Thus, two lonely hearts come together as one in spite of being cast aside as unworthy by the standards of the time. How they come together, slowly but cautiously, is accomplished through conversation and getting to understand one another's feelings.

Both artists went on to further their careers, Steiger in films and Marchand in theater and television. Taking nothing away from either Borgnine or Blair, who was "prettier" conventionally with respect to her looks, I've always been moved by Steiger's interpretation - credit, by the way, to Delbert Mann for insisting he hold back those tears. "You make the audience cry for you," Mann has told in interviews and in print. By doing so, the performance hits home.

Curiously, Steiger and Borgnine enacted their share of heavies. They both played Italian mobsters: Rod as mobster Al Capone in Al Capone (1959), and Ernest as an opera-loving Italian policeman in Pay or Die (1960). Both joined the Navy in World War II, both studied acting upon their return from overseas duty, and both excelled at villainous or sinister types, usually of an ethnic bent. And both won Oscars for Best Actor.

Steiger was the younger of the two, born 1925 in Westhampton, New York. Borgnine was born in 1917, by way of Hamden, Connecticut. Nancy Marchand was born in 1928, in Buffalo, New York, and became a notable stage actor, while Betsy Blair (born 1923), made a few films in Hollywood, and later in Italy.

Both Steiger and Borgnine were (you'll pardon the expression) "fat ugly, little men." Their triumph is our triumph. One could coin the phrase "they knew the type well" without the slightest exaggeration. That's rich, all right!

Copyright © 2023 by Josmar F. Lopes