Adrienne Buller is a thirtyish British think-tanker. Her 2022 book, The Value of a Whale, is subtitled On the Illusions of Green Capitalism. Referring to tackling climate change through market-based approaches, incentivizing needed actions, as with a carbon price, carbon tax, cap-&-trade scheme, or carbon offsets, and “socially conscious” (ESG) investing, etc. All critiqued as flawed and ineffectual, no way to tackle what Buller deems an extreme crisis facing humanity.

The value of a whale was actually the subject of an International Monetary Fund study. We are of course meant to think that the very idea of putting a dollar value on a majestic living creature is crass and tacky. Thus the book’s title — embodying its ethos of prioritizing planetary health above money-grubbing “capitalism.”

True, the planet is beyond price — money is meaningless if Earth becomes uninhabitable. But that’s an extreme (and, so far at least, extremely unlikely) scenario. More realistically the question is the extent of environmental degradation and what we’d have to sacrifice to forestall it (or cope with it). Life is about tradeoffs. A choice between lower living standards and a worse environment is not obvious.

Buller notes that the IMF researchers came up with $2 million for a whale’s value, based on its contributions to eco-tourism and, mainly, carbon capture, reducing global warming. Hence they suggested investment in whale conservation, costing, she writes, “a modest $13 per person on Earth.” And this, on the first page, shows Buller’s mindset. Thirteen bucks may seem “modest” to an affluent brainy Brit. But masses of people earn less per day — or, indeed, per week. They might not be so ready to give up even one dollar for whales.

The book is full of voiced concern for the world’s poor. But they seem like an abstraction. Not flesh and blood.

“Green capitalism” Buller indicts as mostly greenwashing; just another gimmick for finance folks to make money. Surely much truth there. And she’s surely right that, by themselves, such measures won’t halt climate change. Yet so intense is her hatred for “capitalism” that she seems to reject market-based measures altogether, even as part of a larger toolkit. If climate change is such a huge menace, shouldn’t we try using every possible remedy?

Buller also doesn’t think technology can help much. For example, we’d need a lot more lithium, vital for many low-carbon technologies like electric car batteries; but she blasts lithium extraction as environmentally nasty. So she excludes that too.

Her answer instead — though she won’t plainly say it — is reducing living standards. She doesn’t face what this would actually entail for actual human beings — especially all those who’ve struggled to escape the poverty she bemoans. There’s no recognition of what she’s really asking them to sacrifice.

Even the affluent are asked to live, well, less affluently. We hear much about air flights adding to carbon emissions. But such travel has great value for us, it enhances quality of life. That’s just one example, illustrating what Buller refuses to confront. She wants people to accept poorer lives today for the sake of ones in the future whom they’ve never met. People naturally resist that. It’s the key reason why the sort of climate action she envisions is such a hard sell.

It should be imposed by force, Buller is really saying. Rejecting, again, market-based and incentivizing climate approaches, she thinks instead governments must lay down the law, requiring people to do what they can’t be induced to do voluntarily. She may be right that otherwise, we’re not biting the bullet. But nor does she bite the bullet of what she’s really advocating, in all its draconian coerciveness.

Furthermore, the left’s eternal faith in government is astonishing given how often it betrays their ideals. Buller forgets that the market-based measures she critiques are themselves government creations. Why expect government to be more brilliant imposing non-market schemes? And more fair to the poor? After all, the affluent and moneyed interests have far more influence over anything governments do. The kind of “direct regulation” Buller advocates is always vulnerable to capture by the very interests being “regulated.” Not to mention the law of unintended consequences. (My whole professional career as a government regulator gave me a healthy skepticism here.)

Like many climate warriors, Buller is also scathing toward fossil fuel producers. As though they’re villainously extracting oil and gas solely to make money, unnecessarily foisting their products upon us. She’s oblivious to the obvious: fossil fuels are extracted, sold and consumed because people need them. Yes, we should be weaning ourselves off them. But that’s a long process. In the meanwhile, stopping use of these energy sources would crash our economies and living standards. Berating oil companies for supplying needed oil is just idiotic. If tomorrow they all declared, “Greta is right! No more oil! We’re stopping now!” — it would be Mad Max time, wrecking civilization far worse than climate change.

Similarly, Buller condemns economic growth, as though it’s some sort of deranged obsession. Of course it’s true that economic growth is, ceteris paribus, bad for the environment. That’s the tradeoff we’ve always made — we could never have risen from the “nasty, brutish, and short” lives endured by our Stone Age ancestors without exploiting Earth’s resources. There’s no free lunch.

But what’s really jarring is Buller (like many left wingers) denouncing economic growth in the same breath as denouncing the lot of the world’s poor. Almost as if blaming the latter on the former. When in fact, of course, economic growth is the great poverty fighter. The powerful economic growth since WWII has converted the world from one where most people lived in extreme poverty to one where only a small fraction still do.

You’d never guess that fact from reading this book, which makes it sound like the opposite has been happening, “the rich get richer and poor get poorer.” Buller flays global financial systems and machinations as designed to suck wealth from poorer nations to richer ones. Which you might thusly think is the cause of world poverty. Never mentioned is the huge factor of lousy governance and institutions, rife with corruption and exploitation by indigenous elites, which so often afflict the poorer nations and keep them poor, with vast inequality. Nigeria, South Africa, and Zimbabwe jump to mind; there are plenty of others. It’s surely those countries themselves (not Buller’s first-world capitalist whipping-boys) bearing the most blame for their stunted economic picture.

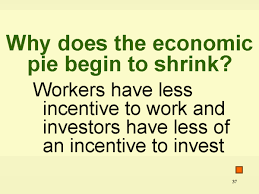

It is true that the fruits of economic growth do not equally benefit all people, the richest doing best. But there is no conceivable economic system in which some people won’t do better than others. That would mean the rich getting richer and the poor poorer — absent economic growth. But with economic growth, even while the rich get richer, the poor can too. Because there’s more wealth to go around, so the poor can get a share, even if it’s not a fully equal share. That’s how poverty is reduced.

Buller types seem to think, instead, that the answer is to just take wealth from the rich and redistribute it to the poor. In fact, taxation does that to a degree. But good luck if there’s a no-growth zero-sum world where everyone is fighting over slices of a static (or shrinking) pie, so nobody can gain without someone else losing. And as world population rises (until, with birth rates falling, it levels off and eventually declines), economic growth will be necessary just to maintain current living standards. Opposing economic growth means favoring mass impoverishment.

And what produces economic growth? Not socialism. Global average real dollar incomes have risen something like sixfold since WWII, with again a massive poverty reduction and improved living standards. This gain has been concentrated in nations participating in a globalized, (relatively) free-trading, market economy, where people can improve their own lot by producing goods and services others need or want. Not a zero-sum world. “Capitalism,” if you will. (Marx’s biggest error was failing to foresee how capitalism would, rather than grinding the masses into deeper poverty, produce mass affluence.)

Yet distaste for capitalism, once more, pervades this book, for all its lamentation that some people are still poor. And of course, as with all indictments of capitalism’s evil, you will search in vain for any glimmer of an alternative system that would similarly make the masses richer rather than poorer. In fact, Buller does seem to endorse impoverishment, fatuously mooning about how life could actually be better, somehow, if we all decided to be satisfied with less.

Tell that to the world’s poor she keeps gnashing her teeth about. If governments did, as she seems to advocate, impose lower living standards, she’d be the first to lament that the rich would find ways to cope and thrive in that Brave New World, while the poor as usual get the short end of the stick.

Anyhow, there’s no attempt whatever to sketch out what her imagined “better” world would look like. Nor how we could conceivably get from here to there. But none of this deters her from demanding “bold changes,” positing “boundless possibility for things to be different.” Ah, the idealism of youth!

By the way, Buller types never seem to grasp that most people in the world earn their livings, and living standards, by working to produce stuff other people need or want. If we all did decide to cut back on “consumerism” and make do with less, a lot of people’s jobs would disappear. They in turn would be forced to cut back and spend less too. Eliminating yet more jobs. Economic growth gone savagely into reverse. A Brave New World indeed.

Meantime — yes! — climate change is a huge threat. And, at this point, rising temperature is baked in, there is no way we can avert some very severe harmful effects. No conceivable amount of emissions reduction can do the job — another reality this book refuses to acknowledge. So while it’s true that “green capitalism” won’t do it, the book’s own approach of imposing extreme governmental action and poorer lives won’t do it either. That too is an illusion. (Even aside from the question of whether voters in democracies would stand for it.)

Dealing with the now-unavoidable effects of climate change will require a lot of resources. Resources that economic growth can provide. If we really want to save ourselves (and especially the poorest), we’d better grow our economies as much as possible.

Advertisement