Copies after George W Lambert, at the Art Gallery of NSW and at the Julian Ashton Art School

An especially excellent thing about spending all my time at the Atelier is that I get to rub shoulders with a host of talented artists who have approached their careers in a variety of ways. The Salisbury Studios are aligned with and located at the school, and on any given day I can wander into someone’s studio and learn something about their work, and their approach to their work. Since I’ve become a part of the furniture there, no one seems to mind my evident curiosity and occasional (invited) snooping.

I recently spent a little time pottering around Kay Kane’s studio, admiring a portrait of an academic she had recently completed, as well as some lush, misty landscapes at various stages of layering. Kay’s work is usually on a large scale, very grounded in drawing from life, and the often multi-panelled works are carefully composed arrangements of enclosing shapes echoing real Queensland landscapes, painted in oils in airy hues. The vastness of the paintings envelope the viewer, drawing you into Kay’s peaceful haven.

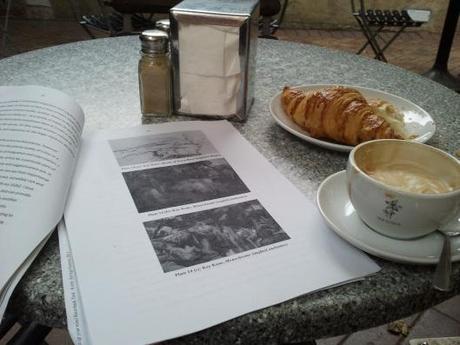

Three panels from The Restoration of Venus © Kay Kane

Kay works at the Queensland College of Art (QCA), where her representational approach to art is, as I understand it, not especially respected. It’s alarming to learn of the battles a representational artist faces in the modern art world, but reassuring to see skilful and established artists like Kay standing their ground and being true to their convictions regardless. Her career, then, has been an academic one as well, which sees her jetting off to California to present papers on misogyny in art, as well as teaching at a university and submitting exegeses of her own. She gave me a copy of her Doctor of Visual Arts exegesis to read, which made for some pleasant breakfast reading in Sydney, and gave me plenty to think about.

Titled The restoration of Venus: The nude, beauty and modernist misogyny, her paper largely deals with the place of beauty in art, and whether the modern artist can include the undeniable beauty of the female nude in her visual repertoire to any meaningful end. The project grew out of her ‘persistent interest, not only in pursuing traditional modes of art practice, but in creating works intended to be beautiful. … If I seek beauty in my own work,’ she explains, ‘it is because it is there in the world to be found’ (p. 29)—and, perhaps, to be found for a reason. I would add to her sentiment that of Elaine Scarry (p. 81) in her treatise On beauty and being just: ‘It is as though beautiful things have been placed here and there throughout the world to serve as small wake-up calls to perception, spurring lapsed alertness back to its most acute level. Through its beauty, the world continually recommits us to a rigorous standard of perceptual care: if we do not search it out, it comes and finds us.’

Surrounded by artists who feel similarly about beauty, it’s easy for me to forget that the broader art world is concerned with things it might consider ‘higher’ than beauty, wrapped up as I am in my philosophical ideas on truth, beauty and good. Scarry (p. 58) writes of the fear that beauty distracts from real issues, from political injustices that art could help rectify if we weren’t so busy admiring the world and others, an argument she seeks to knock down. While her reasoning is less than rigorous, her intentions are noble, and align with my view that there is a place for creators of beauty in a world polluted with injustice: ‘It seems almost inconceivable that anyone with affection for human beings could wish on them so harsh an edict, permitting only perceptions that bring discomfort’ (p. 60). We must live towards some end, some beautiful end, not be forever evading an unpleasant present.

Kane recognises that art need not be beautiful to constitute art, but argues that shunning beauty in preference for these harder issues ‘did not succeed in expunging the human desire for and responsiveness to beauty.’ Further, as beauty was pushed aside in fine art, it resurfaced elsewhere, and the female form was carried along with it: becoming ‘more blatantly deployed, often in debased form, in popular culture. … It has never ceased to exert its power and fascination at the level of popular consciousness’ (abstract; p. 24). She seems to imply that were artists not ashamed to embrace the genuine beauty of the world and of people, to present something powerful and moving in a positive sense, to appeal to the visual hunger of the broader public for something delightful to the eyes, though not shallow and not a flashy veneer, that such artists would be responding to something very real and relevant in the human condition. Taking up this mantle might even prevent this desire from falling to cheaper, more vulgar incarnations. In denying something so fundamental to human nature, art has itself contributed to the devaluation of beauty. Art, then, is in a position to restore meaning and worth to beauty, and to bring it again before our eyes in a more intellectual and enduring way than popular culture might.

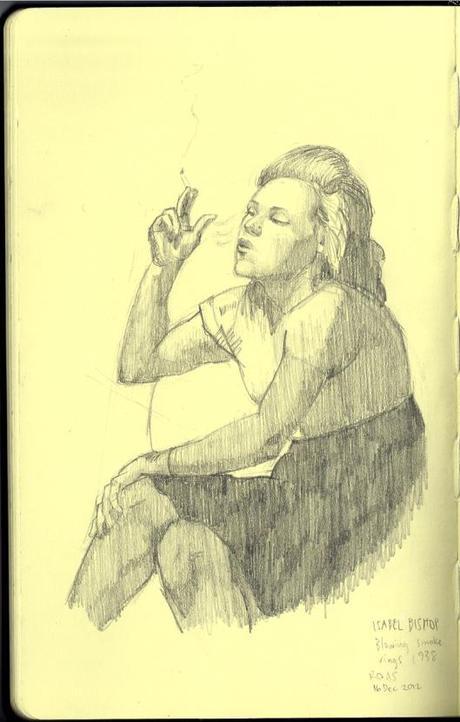

Copy after Isabel Bishop

Aside from considering the role of beauty in art, Kane describes at great length her actual method of creating her works, an enlightening insight. Much attention is given to composition, with ‘links in chains of bodies’ sweeping through and connecting the landscape and figures. These links ‘may be obvious continuities like linked hands, successions of arms, clusters or groups of forms. They may also be articulated by tonal pathways or continuities or echos of colour from one shape to the next’ (p. 40). Other compositional links are ‘purely notional’ or ‘invisible connectives’: ‘the vector of a pointing finger, or a glance bridging a wide interval, or a particular patterning of feet’ (p. 40). Kane’s deliberations on these connectives recalls to my mind Robert Nelson’s (p. 12) claim that ‘composition is an expressive resource, not a formalist absolute, … it relates not just to the subject matter but to the construction of space and hence drawing.’

Drawing is, for Kane, fundamental to art. ‘It is in drawing above all that one learns to see,’ she asserts, citing Robert Henri: ‘It is harder to see than to express’ (p. 30). There is an intentionality to drawing, in that it forces one to internalise what is seen and to reconstitute it on paper by a series of decisions. Nelson (p. 54) argues that ‘drawing is all about decisions,’ and, further, that it ‘involves authority.’ One draws to elucidate, to describe, to understand, and in so doing one must make decisions about what the crucial elements are that lay before one’s eyes. ‘Your decisions about what is important and your choices to manifest this or that designate your power to stipulate what must be seen’ (p. 54). Kane’s project is grounded in perception of, observation of and representation of the external world and the beauty it continually sets before us, rather than some inward ideas or unbridled expression.

This brings us to the least tangible, but perhaps most profound element of her work: the notion of the unsayable. This idea strikes a chord with me, as well it might with anyone with a deep love of music. Any musician can testify that music is compelling in its capacity to say things without words. It doesn’t say clear or mundane things, like, ‘can you please wash the dishes,’ unless you set such lyrics to it. But notes and timbre and chord progressions speak to a languageless part of us and say those things which we struggle to put into words. Art can have this quality. While some art is intended to represent words or concepts, or to narrate a story (and I am thinking of illustration), some art speaks to us in purely visual ways. Something about a painting can just sing. This is not to say that words are irrelevant or less important, but simply that there are other ways to connect with people. Kane (pp. 29-30) cites Walter Sickert who aptly remarks: ‘If the subject of the picture could be stated in words there would be no need to paint it.’

Kane suggests that an artwork’s meaning, far from resting in a lengthy artist’s statement, might lie solely in this wordless, purely visual resonance. She urges us to accept that some things are simply unsayable and we ought to let art step up and do what only it can do. ‘By trying to reduce what is essentially unsayable to handy formulas of trite categorisations,’ she argues, ‘one risks being untrue to work whose meaning, if it has any, lies wholly within itself and nowhere else’ (p. 1). I think she really wants to say that art is eighty percent science, twenty percent magic—and this captures something very profound and too often disregarded.

Kane, Kay. 2010. The restoration of Venus: The nude, beauty and modernist misogyny. Queensland College of Art, Griffith University (Doctor of Visual Arts exegesis).

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.

Scarry, Elaine. 1999. On beauty and being just. Princeton University Press: Princeton.