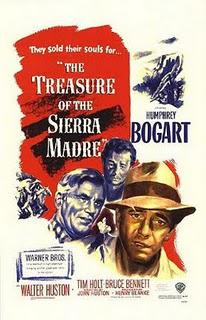

The Blu-Ray cover for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre depicts Humphrey Bogart in a moment of sober, slack self-recognition, a repulsed and vacant stare into nothingness. A more representative image, however, would have been one of the countless looks of uncontrollable hunger and desire that crosses Bogie's face throughout this vicious fable of greed. Like his greatest performance in Nick Ray's In a Lonely Place, Bogie's work here channels the actor's vulnerability into a self-annihilating fury, an unfocused explosion of fear and loathing that can consume anyone caught in its blast radius.

The Blu-Ray cover for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre depicts Humphrey Bogart in a moment of sober, slack self-recognition, a repulsed and vacant stare into nothingness. A more representative image, however, would have been one of the countless looks of uncontrollable hunger and desire that crosses Bogie's face throughout this vicious fable of greed. Like his greatest performance in Nick Ray's In a Lonely Place, Bogie's work here channels the actor's vulnerability into a self-annihilating fury, an unfocused explosion of fear and loathing that can consume anyone caught in its blast radius.When we first meet Bogart, as Fred C. Dobbs, we see the actor at his most vulnerable, shuffling around a harsh Mexican town with no prospects bumming pesos off fellow Americans. Bogie's hangdog expression has never drooped so low; if it sagged any further the flesh would fall off his skull. But when he and compatriot Curtin (Tim Holt) hear about a potential gold vein from an old prospector who's played his luck enough to squander the fortunes he's made, the men drag the old-timer, Howard (Walter Huston), with them on the hunt for gold, utterly ignoring the warnings made to them.

John Huston wastes no time delving into the film's macabre moralism: he introduces Howard in a seedy, cheap motel room where bums share a giant space in rotting cots rambling on about the evils of gold and how he's back here in the dumps after finding his share of wealth, but all Curtin and Dobbs can think of is those mountains of gold Howard says undid him. Howard cautions that the yellow stuff changes and corrupts people, something he himself proves when he instantly agrees to join the men's expedition. After his borderline soliloquy on the evils of gold, he goes right back to being a slave to it.

With his sturdy, uncluttered compositions, Huston uses his honed workman style to greatest effect here. Using a dusty, hollow mise-en-scene, vast enough for howling winds and kicked-up sands to swirl around the triumvirate of losers, the director leaves gaps of space in his tight 1:37:1 frame to let the atmosphere accumulate over the men. When those sandstorms die down, all that's left is static, arid air that crackles with the electricity emanating from the three as the gold they actually discover begins to addle their brains.

And no one loses sight of his humanity faster than Dobbs. Bogart runs the gamut of his range in this movie, from the always-on-the-verge-of-tears look of infinite sadness on his face to animated glee at the thoughts of rivers of gold. But it's that aforementioned naked greed, that twisted, paranoid avarice cracking the caked dirt and sweat along evil wrinkles. Having gone bald from alcoholism and hormonal injections to help conceive a child with Lauren Bacall, Bogart wears a wig that doesn't look fake (it's too damn dirty to tell) but suggests a receded, eaten away scalp underneath the thick, unwashed lump. His smile is as unsettling as the look of ecstasy in his face as he imagines the murder in In a Lonely Place; his grin is gap-laden, jagged and grimy—you can practically see a thin film of plaque on the teeth. When Bogie gets this look on his face, Satan himself wouldn't rush to collect this damned soul.

Dobbs' descent into madness is exacerbated by the dangers the trio face in their trek. The train they take to get to the area is attacked by banditos. The cave they dig out to extract gold collapses on Dobbs and jars his head. Another gold hunter follows Curtin back from a trading post, forcing the three to consider whether to cut him in on the work to ensure the secrecy of their dig or kill him and face both the risk of being discovered and the moral repercussions of killing for money. At last, a group of banditos ascends the mountains, having bought the miners' ruse of being hunters but come all the same for guns and ammunition. All of these issues weigh on Dobbs' mind, splintering the focus on his distrust and anger until he can no longer find his way back to sanity after his outbursts.

Huston's great strength was his economy, but he takes his time out here in the Sierra Madre range, not only letting the space air out the narrative without losing flow but even throwing in a few extraneous scenes that successfully add flavor without feeling like add-ons. The most memorable of these is a moment late in the film when Mexican Indians emerge from the dark politely requesting help in reviving a semi-drowned boy. Howard heads out with them, leading to a beautiful, strange scene of the old man using pre-CPR methods to work some life back in the boy as an almost impossible number of Mexicans stand by in this tiny village, as if Aztec ghosts suddenly appeared behind the gathered corporeal beings to monitor the future of this latest descendant of the bloodline. That scene is so striking in and of itself that its mesmerizing, almost dreamy quality somehow fits within the stark moral desert of the rest of the film's tone.

But that scene also serves to demonstrate the different moral states of the men. If Dobbs rests at one end wholly consumed by his greed, Howard has achieved a self-aware wisdom that may not prevent him from still going out on these damn fool digs but gives him the clarity to rise above the corrupting influence of gold and to entrust his goods with the others to do the right thing and help someone. In the middle is Curtin, whose own corruption is handled more subtly than Dobbs'—when the mine partially collapses on the latter, Curtin has a brief moment of hesitation, the look on Holt's face suggesting, if only for a millisecond, that he could leave his friend and partner to die and take his share. But he also has flecks of humanity and decorum, tiny displays of better judgment that only further strain his relations with Dobbs.

Their various levels of temperance in the face of gold's influence bear out in their ultimate fates. Like a Coen brothers film, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre shoves its grisly climax back from the very end of the film, turning what could have been a trite, obvious comeuppance into a removed, finely observed moral reckoning with dramatic space afterward to truly reflect. Dobbs' actual demise is blunt, half-seen, uninviting to audiences seeking a thrill in the villain's downfall, and the critical distance of Huston's lens pulls back as if getting nature's view of the situation. As such, it makes odd but undeniable sense that his death should have nothing to do with the gold and that the stuff should finally return to the mountain dirt from whence it came. Howard and Curtin come to terms with this in gales of laughter: Howard knows that he has a shot at a comfortable twilight with the Indians who respect him, while Curtin is, by his own admission, no worse off than when he started, but now he has the same clarity Howard got through experience and can perhaps carve out some happiness.

Importantly, however, Huston does not resolve solely to fates reflective of one's moral status. Cody, the potential usurper who comes to the camp, helps the strangers who reluctantly agreed to kill him fend off the bandits, and we learn that he sought riches to care for his family, from whom he'd been away for a long time. But he dies in the bandito raid, his own complex, human morality entirely separate from the end that befell him. Make no mistake: The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is assuredly a fable, but Huston does not present his location-shot adaptation of B. Traven's book in a moral vacuum. Cody's death, like Dobbs', is meaningless and inevitable in the unbending, dispassionate view of nature.