INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

A very interesting series of events that no one could have predicted took place in my country this year — a cultural phenomenon, tied to one man, that caused a swell of emotion not often seen in a country that lacks figureheads, or is often perceived to lack them. That man is Gordon Downie. Along with the band he fronts, The Tragically Hip, Downie caused an entire nation to reflect on itself for a moment; it caused the release of a lot of emotions, including pride, but also some discussion of what comprises Canadian musical culture. And that’s part of a larger, ongoing argument in this country of mine over what the heck is Canadian culture anyway? It’s in the context of that greater argument that the significance of this summer’s events becomes less emotional and more interesting. Because the world’s second-largest country has what are quite likely the world’s worst identity issues, not to mention self-esteem problems. Who are we? And why the hell does that matter so much?

The answer can’t lie entirely in the experience a nation following the bravery of a man diagnosed with a particularly virulent form of brain cancer (glioblastoma), going on tour and exhausting himself in front of a country, then putting on a particularly courageous TV experience for millions, bereft of voice and sometimes even memory of the lyrics, but toughing it out over several encores as a nation sang and wept alongside him. But considering the scale of the affection and pride that was stirred up by this event, it may supply some clues.

WHO IS GORDON DOWNIE?

Just to set the stage better, in the late 1980s a fairly nondescript blues-rock band called The Tragically Hip scored a record deal. That was something of a time of flowering for the Canadian recording industry, which had its successes in the 1970s and early ’80s with acts like The Guess Who, Rush, April Wine, and Anne Murray. A thriving industry had been established, and with each musical trend that came along, homegrown acts were found to fill the public’s appetite for local talent. Mostly, those talents aped styles from places like London and New York, which is what happens internationally with pop music. Canadians made quality pop music but were rarely creators of trends.

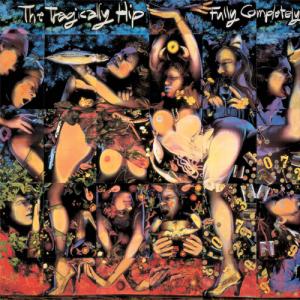

But it wasn’t until a few albums in that Downie went from successful frontman to totem for a nation. The 1992 album Fully Completely saw the band breaking out of the blues box a touch, adding a harder and occasionally less stridently pentatonic, more progressive element to their sounds. Downie’s predilection for Canadian imagery was no doubt totally honest and uncontrived (historically, there’d been little to gain from name-checking uncool Canadian things), and it’s not like a Canadian folk tradition (think Stompin’ Tom Connors or Stan Rogers) didn’t already exist that extolled the virtues of Canada and its history. He was just doing his thing.

But it’s fair to say that such imagery hadn’t much entered the pop world. Hence, top-40 artist Downie singing a lengthy ballad about a specific man who spent decades behind bars for crimes he didn’t commit — in Saskatchewan, not Texas — or bellowing lyrics about a hockey player from the 1940s seemed entirely fresh and original — and even important. Funny that singing about things close to home would seem radical, but it was.

Compounding the nation’s love for the band was the fact that The Tragically Hip failed to gain a large audience abroad, probably more due to a lack of consistent label support than the international music listening community’s unwillingness to appreciate its “Canadianness”; hence, it was felt that the band remained Canadians’ exclusive possession and well-kept secret.

This hummed along till 2016, when the announcement of Downie’s cancer and farewell tour set off a frenzy the likes of which the country hadn’t seen. Granted, let’s admit that we live in an era when any public event turns into a free-for-all on social media, with everyone expressing their totally unprofound and unoriginal personal opinions over and over, the mainstream media catching on and publishing articles from every angle it can possibly find, until anyone with any sense gets sick of hearing about even very worthy and important people and causes.

I felt that way about this basically until I saw the final concert, viewed by over 11 million people (almost a third of the population), and fought off the tears myself. This music had never been that important to me, though I liked a song here and there and once owned a cassette of an album. What was it about this particular event? The human drama? The sadness of seeing people’s impending loss? The nobility? Or realizing that I knew far more of these songs that I’d realized, and that I actually liked a lot of them? It’s interesting to find that something was part of the fabric of your life without ever having realized it. And that was the “Canadian” part of my life; I wasn’t born here but gradually learned more and more and discovered about the place until I even ended up living in a small town.

After the TV concert, I found myself trying to explain what the heck this was all about to bemused older relatives, which got me thinking along these lines,. My mother was born in Wales and moved to Canada in her twenties. She doesn’t much like rock music. How could I explain this to her in a greater cultural context?

WHAT IS CANADIAN CULTURE?

I work in the publishing industry. Well, I did. I freelance now, which means I guess I camp out on the periphery of the industry. Even more so than the music or film/TV industries, publishing has been saddled with answering this question, one that it could be argued didn’t need to be asked in the first place. And yet it has been asked, ad nauseum.

The reasons for that are perhaps simple. There are very few English-speaking countries (Canada is of course bilingual, but French-English cultural issues vs. identity are the subject for a whole other essay). Some, like Australia, are on the other side of an ocean. Canada is in the position of butting up against the dominating force of the US. And since Canada is a former British colony, UK culture is always nosing its way in too.

As a country of immigrants, the importance of the original French/Anglo-Scots-Irish (and Indigenous) nature of the culture has increasingly declined with the promotion of a multicultural ideal in which all cultures contribute to a vibrant and happy mixture, as contrasted with the US view of such things.

And yet unity as a nation appeals to the instinctive tribal nature of humanity; we need to feel a kinship with those around us, a closeness in values and culture that makes us feel part of something greater. So it would seem, anyway. And nestled up against the world’s most jingoistic nation, where national pride is a religion, and one with a huge population that sends out billions of dollars in cultural product every year to entertain the world’s masses, it’s easy for Canadians, who watch US TV, listen to US music, and read US books, to forget that there might be something unique about the people who inhabit these ten million mostly empty square kilometres. How do we find that unique bond in such a scattered populace from so many different origins?

So, in the interest of having a unified body politic, the pointy heads of Canada’s intellectual world decided that we needed to know who we were, and that our culture should reflect that. Particularly, our arts culture. And the arts was tasked officially by the government with determining what it meant to be Canadian, and promoting that vision.

THE MANIPULATED CANUCK CULTURE MANDATE

That seems a noble endeavour, doesn’t it? In order to make sure there were Canadian artistic products available that reflected the people, places, and issues or this country, the incentive of well-funded grant systems was created. Music, books, visual arts, etc., are “supported” by institutions like The Canada Council for the Arts, provincial arts councils, and others, which ostensibly supply funding for the creation of works of art that are of high quality and present the Canadian identity to the world at its best.

And there the problems start. You can’t just write a book or make a CD and have it be judged fundable; that would be impractical. And apparently rewarding companies that produce Canadian content based purely on a consistent output and employing workers in the field isn’t enough either. Arts grants and, of course, awards, are juried, meaning that some panel of respected notables is put together to assess the intangible worth of the submitted art. And that’s really where the problems start.

It has led to the creation of a cultural clique based around the concept of high art; in publishing that means “literary” fiction that is mostly highbrow, poetic, and therefore not all that appealing to the average reader. Such works are considered to be the best of Canadian art and identity, despite the existence of more “commercial”, plot-based art replete with Canadian characters and settings. Many if not most readers tend to enjoy what is called “genre” fiction — romance, mystery, science fiction, some of which actually does contain a “literary” value; it can be said with some certainty that hardly any novel is written purely for entertainment value. Everyone, including a crime fiction writer, wants to make a difference, right? But if you want funding, the formula goes, publish literary works as often as possible.

The effect of financial rewards being given to people and companies that satisfy the requirements of a certain vision means the exclusion of those that don’t — even if their work does actually show the faces and places of the country, which is ostensibly the point of the reward in the first place. It’s not all bad; the industry has made some effort to show the diversity of Canada by funding works by new Canadians and Indigenous authors.

Over time, though, this meddling doesn’t reflect culture; it creates it. And who gets to create it? The vision becomes controlled by an elite, and that is presented to the public as the content worthy of consumption. So writers of genre fiction and certain nonfiction have lacked support in struggling to gain a foothold in the US- and UK- dominated territory of their field.

Frankly, much the same scenario has played out in Canadian film, with “arty” product dominating, and more commercial films with Canadian settings are hard to get made.

The point of my telling you all this is that in attempting to establish what it means to be Canadian, the arts poobahs ended up creating an elitist system wherein certain people make art for the benefit of themselves and a small group of educated people interested in or capable of appreciating their works, and then cosy up to the funding and exposure available only to them.

It’s the dark side of cultural engineering.

Why this discussion of non-music-related things on a music blog? First, you’ll get a Hip-related metaphor later. Second, I wanted to show the lengths to which the cultural establishment in this country will go to creating and then maintaining a certain very controlled vision.

MUSIC’S ROLE IN CREATING AN ARTS INDUSTRY

Governments also promoted the idea of a Canadian musical culture through the institution of “CanCon” regulations on radio, which prescribed that a certain percentage of radio plays must be Canadian in origin, based on a formula (the current percentage is apparently 40%). Depending on which side of this argument you stand on, this is either an excellent tool to promote local talent, or a watering down of the railways through endless repetition of Bryan Adams’ “Summer of ’69” and other hoary chestnuts that radio can’t and won’t forget. It’s probably fairer than a grant system, because if you’re popular (there’s the rub) and a station exists that plays your kind of music, the rules make it possible for you to get played. No panel of prize-winners is deciding whether you get a spin.

Grants are also available to labels and to artists. From my own experience, the music establishment is not as dead-set on the idea of promoting an elevated artistic culture as the publishing industry is; after all, rock and pop are where the money is, and increasingly, urban music. You can’t justify a system that only funds classical and jazz artists.

Nonetheless, CanCon is another example of attempted cultural engineering by our powers that be — if we can’t stop the flow of Anglo-American culture over the border, we will legislate the flourishing of our own culture by manipulating the airwaves.

That’s the negative view; the positive one is that the artists are going to be there anyway, struggling; so why not support them? I personally just wish there was a fair and equitable way all this could be achieved.

WHY IS THE TRAGICALLY HIP THE “PEOPLE’S BAND”?

The Tragically Hip may have gotten their share of music grants and airplay, but it’s established that their success was far more organic than just being pushed on the public by regulations; it was done through relentless touring and building up an appeal with audiences from all walks of life. Rock music has always been the people’s music, even if major corporations were peddling it; Stockhausen didn’t have any top-ten hits. If something could unify a population, is there a better candidate than popular music?

So, after all this verbiage, can we answer the question, how does the Hip reflect Canada better than a famous Canadian fiction writer? Does a fellow being popular for that long, and in one country only, primarily by utilizing Canadian themes and scenes, make him the musical or even the very cultural voice of a country? Is this just a (social) media-produced frenzy, or is the band really the heart and soul of Canada’s musical culture? (I suppose another question could be whether they are really just the heart of Canada’s white musical culture, but that’s also a whole other subject.) The truth is not at either extreme, but what I do believe is that The Tragically Hip are the musical equivalent of a really good genre novel that appeals both to intellectual readers and the common man; the mostly meat-and-potatoes rawk tunes fill the arena and get fists pumping; the sometimes rarified, poetic bent in Downie’s lyrics can appeal to the intellectual elite who would usually reserve their approvals for other, more deliberately obscure and arty indie acts. In some way this transcends even the appeal of Rush, an intellectual band that started in another era and has a more international appeal and a less specifically regional flavour, while still being down-to-earth and accessible.

There’s no question that whether you are one of the band’s regular guy/gal fans or a smarty-pants, the cultural appeal lies in Downie’s enthusiastic embrace of Canada’s history and people as the wellspring of his inspiration (his possibly last project is a concept album about an Indigenous boy — a fitting last shot across the bows of the country’s rulers), and I’m hard-pressed to think of many rock acts that have done this — certainly not one with such widespread appeal. That uncomfortable union of the band’s gritty rock ‘n roll and Downie’s artistic ambitions creates a tension you only find in the best art. It’s in bridging the worlds of artiness and rockingness that the Hip conquered.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

The lesson here is that while you can try to prescribe culture, deliberately engineering a vision of what a country “means” when compared with its neighbours, the most effective art that brings the most people together is created more organically; from humble beginnings and from touring around this country, Downie clearly came to an understanding of Canada’s people in their diversity; not only in the cities where the money is spent, but in smaller towns and Indigenous nations as well. This determination that Canadian stories had value, delivered unpretentiously and with passion, makes The Tragically Hip worthy of the success and most of the hype that has recently been attached to them. You can legislate cultural exposure in the marketplace, but you can’t manufacture an artist who is capable of reflecting the people’s world back to them with empathy, thus winning their love. This lesson should be applied to all arts. Don’t act Canadian in whatever way you’ve been told that is — just be here, as you are, and reflect back and comment on what you see, without artifice or false national pride. If there’s a national value with which we want to be associated, it’s that sincerity in his music as well as the courageous way Downie has chosen to live out his days.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION