Book Review by George S.: I’ve read reviews on the internet complaining that The Toll-Gate is not a proper ‘Regency Romance’ in the usual Georgette Heyer manner. It isn’t. It’s more of a comedy-thriller romp set in the past – and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

The hero is Jack Staple, a huge man, a Captain in Wellington’s army in the Peninsula, who had tried to settle down after that war, but when he heard that Napoleon had left Elba, immediately re-enlisted as a trooper. Soon restored to the rank of officer, he fought at Waterloo. Now that campaign too is over, and he is at a loose end in England, and bored.

His mother suggests that he would have been happier living in archaic times, when he could rescue some female from a dragon or an ogre. He replies:

‘Famous good sport to have had a turn-up with a dragon. As long as you didn’t find yourself with the girl left on your hands afterwards, which I’ve a strong notion those fellows did.’

The bored ex-soldier hungry for adventure is a standard character of twentieth-century thrillers (I was reminded of Bulldog Drummond, for example). Georgette Heyer puts the type back into the early nineteenth century. Did they exist back then? Maybe.

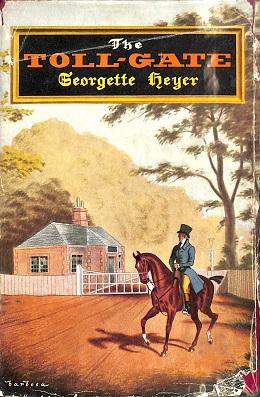

Captain Staple’s adventure begins when he comes across a toll-gate whose guardian has gone missing. The man’s son is there, and frightened of someone. Staple decides to stay to see what is happening, and takes over the operation of the gate. Mysteries multiply, and soon he begins to take an interest in what is happening at the local big house.

Old Sir Peter Stornoway is at death’s door, and his daughter Nell is anxious about him, not just because of his medical condition, but because of the sinister visitors at the house. Nell Stornoway is uncommonly tall, and a good horsewoman. She had spent a coming-out season in London, but had deeply disliked it, because at dances all the men were shorter than she was, and so she lacked dancing-partners.

Since Captain Staple is himself huge, however, he likes the look of her, and since she is also attracted to him, the reader never has any doubt about how the book will end. this is not one of those will they or won’t they romances.

The complication comes in the form of her cousin Henry, heir to the property, a weak man under the thumb of a nasty piece of work called Nathaniel Coate. Georgette Heyer tells us what to think of Coate by describing his clothes:

Coming towards the gate, on a showy-looking hack, was a thickset man, rather too fashionably attired for his surroundings. He wore white hunting-tops, a florid waistcoat with several fobs and seals depending from it, a blue coat with long tails and very large buttons, and a beaver hat with a exaggeratedly curled brim.

The clothes tell us all we need to know about the man. He is a wrong’un.

This novel is typical of the light thriller genre in that the obviously nice and decent people remain nice and decent throughout, while those labelled bad at the start will go on to consistently confirm the diagnosis by their actions. Another standard feature of this type of book is the behavior of the servants. All the servants (dependable salt-of-the earth types) are utterly loyal to the old Squire and to Miss Nell, and none of them have a good word for the weak cousin or the crooked Nathaniel Coate. (I was in this respect reminded of the Dornford Yates novel I reviewed here a while ago, where once again thr loyalty of servants is an infallible index to the characters’ moral worth.)

There are some interesting minor characters – Chirk is a highwayman, but very aware of his social position at the top of the crime hierarchy. Stogumber is a grumpy Bow-Street Runner whose search for stolen gold brings him into the plot. Jack’s posh friend Babbacombe is amusing – especially when he incongruously takes over for a turn at the tollgate, and argues with all the customers.

This isn’t a romance that Georgette Heyer is very serious about. She obviously likes her hero and heroine very much, but is rather amused by these two very tall people falling in love. The obligatory scene in any romance is the one where hero and heroine kiss with passion, giving themselves to one another. In many Georgette Heyer novels this kiss is delayed until the last chapter – even the last page. In this one it comes half-way through the book, and the author obviously likes her tall hero and heroine, she is perhaps not taking them completely seriously, since she lets them be interrupted by Beau, Captain Staple’s horse:

“She lifted her head, looking wonderingly up into his face. The next instant she was in his arms, crushed against his great chest. He spoke magical words: ‘Little love! My dear one!’ No one had ever called Miss Stornaway little before, and never had she felt so little, or so weak. Captain Staple was holding her with his left arm only, his right hand being employed in pushing up her chin, but it was far too strong a hold to admit of any possibility of escape. She attempted none, but lifted her face in the most natural way, like a child asking to be kissed. Captain Staple, tightening his hold on this vital, yielding armful in a manner as gratifying as it was uncomfortable, responded to the mute invitation promptly and thoroughly, and forgot the world until Beau, possibly affronted by such behaviour, or perhaps hopeful of further largesse, nudged him with sufficient force to recall him to a sense of his surroundings. ‘Damn the brute!’ said Captain Staple, removing himself and his love to a bench over against the wall. ‘My darling, my darling!’”

The book is readable, and the action carries the reader along nicely, but I think I might have got bored with it if it wasn’t for the language.

Georgette Heyer took her Georgian research seriously, and in this book she is keen to show off her knowledge of period slang. She ladles it on. Here’s Captain Jack accusing Chirk of being a highwayman:

‘Was that when you took to the bridle-lay?’ John asked. ‘A peevy cove, ain’t you?’ Chirk said. ‘What d’ye want to do? Cry rope on me? Who told you I was on the bridle-lay?’ ‘Who told you I was a green ’un?’ retorted John.”

Chirk accepts that people in his line of work are liable to end up hanged: “The chances are you’ll go up the ladder to bed – at York Gaol, with a Black-coat saying prayers, and the nubbing-cheat ready to top you.” The book is peppered with this sort of language; it is full of leery coves, sapskulls, bridle-culls, gabsters, goosecaps, bartholemew babies, rank riders and so on. It’s clear that Georgette Heyer hugely enjoyed her research into the byways of Georgian slang, and she communicated the enjoyment to us. It’s that kind of book – one here the author shares her pleasure with the reader in a companionable sort of way. I had a good time reading it.