Stories have endings; that’s why we tell them, for reassurance that there is meaning in our lives. But like a diagnosis, a story can become a prison, a straight road mapped out by the people who went before. Stories are not the truth.

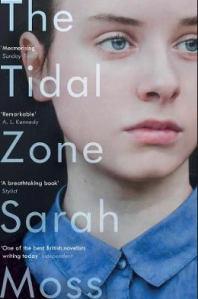

Rave reviews of Sarah Moss’ The Tidal Zone caught my attention and I decided I had to read it. I’ve read two of her earlier novels, Cold Earth, a stunning ghost story, and Bodies of Light, a mesmerizing historical novel. I enjoyed them very much and was pretty certain I would love The Tidal Zone as well. Unfortunately, I was wrong. I liked it but didn’t love it. I’m not exactly sure, why I didn’t warm to this ambitious book. It offers so much. Meditations on life and death, gender, politics, family life, illness, the NHS . . . I could go on.

It’s the story of a family that almost unravels when the heart of the 15-year-old daughter, Miriam, stops. Miriam survives the episode but has to stay at the hospital for a long time as it’s not clear what brought on this reaction. She seems to suffer from some type of allergy. Adam, a stay-at-home dad, spends most of his time at her side, only occasionally replaced by his overworked wife, a doctor, who works for the NHS.

Many reviewers called this a “state of the nation” novel and that’s accurate. It definitely looks at the way people live in Britain now. Or rather, the way middle-class, white people live in England. Adam’s a bit of a failed academic and is working on writing something about the Coventry cathedral. The book alternates between reflections on the cathedral, which was, along with most of the city, destroyed during WWII. Like Miriam’s incident, the stories that are told in these parts are about human frailty and the unpredictability of life. But they also help to illustrate the family history as Adam’s Jewish dad was born in the US. The family fled Europe during the war.

Fiction is the enemy of history. Fiction makes us believe in structure, in beginnings and middles and endings, in tragedy and comedy. There is neither tragedy nor comedy in war, only disorder and harm.

While I didn’t warm to this book, I enjoyed many of its parts. This is a family of intellectuals who seem to love a good argument. The descriptions of family life are often hilarious. Miriam’s a great, great character.

Here’s her answer to her dad’s question whether she’ll go with him to Coventry cathedral:

It’ll take more than coloured glass and old music to make me sign up to homophobia, misogyny and the grandfather of all patriarchal institutions.

She’s bright, very political and engaged. She will never let anyone get away with bullshit. It was so refreshing to read their repartees.

She had joined Amnesty International and Greenpeace and the Green Party. She said patriarchy and hegemony and neo-liberalism, several times a day. She put streaks of blue in her hair and enjoyed baiting her teachers by wearing mascara: but Miss, you’re wearing makeup. But Sir, aren’t you just inducting us into a world more interested in policing women’s sexuality than giving us knowledge?

Obviously, this isn’t your every day family as Adam’s a stay-at-home dad. While it does sound like hard work at times and he makes huge efforts to ensure that the family always has clean clothes, nourishing, healthy meals and that the house is clean and tidy, we never hear it mentioned that he struggles. I found that interesting because I can’t remember every reading a novel about a stay-at-home mom who also was an academic and tried to get work done and it sounded so harmonious. I wonder if that was a conscious choice and if so, why. I remember that the mothers in Sarah Moss’ earlier books struggled quite a bit with motherhood.

As you see, there’s a lot to love here. So why didn’t I warm to this? The book had the misfortune of reminding me of Ian McEwan’s Saturday. None of the characters is even remotely as obnoxious as those in Saturday, still, there’s a similarity. Probably because the characters both occupy the same social territory. Or maybe I didn’t warm to this because Sarah Moss tried hard to show us another side of her talent. While the other novels I read were very atmospheric and spoke to the senses, this one speaks purely to the mind and – depending on the reader – to the emotions. Since I had no emotional reaction to this, it spoke only to my mind, which wasn’t enough for me to love it.