Fritz Lang stood out as the first master of sound cinema by making talkies that, ironically, seemed quieter than his silent epics. Films like Die Nibelungen and Metropolis are gargantuan affairs with so many moving parts that you can practically hear gears turning, set to bombastic scores of Teutonic music. Starting with M, however, the music dies, invoked only through troubling diegetic means like the killer’s whistle in that film, or the deranged humming in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Even in Lang’s Hollywood films, where a score is imposed, there are moments of eerie silence, none more gripping than in the opening of 1941’s Man Hunt. In the place of bombastic music, that felt sound of machinery from the silent films can now be literally heard; the first scene of Testament, for example, takes place in a printing press, the roar of printers rocking the room and sounding like a train about to burst through the walls.

Fritz Lang stood out as the first master of sound cinema by making talkies that, ironically, seemed quieter than his silent epics. Films like Die Nibelungen and Metropolis are gargantuan affairs with so many moving parts that you can practically hear gears turning, set to bombastic scores of Teutonic music. Starting with M, however, the music dies, invoked only through troubling diegetic means like the killer’s whistle in that film, or the deranged humming in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Even in Lang’s Hollywood films, where a score is imposed, there are moments of eerie silence, none more gripping than in the opening of 1941’s Man Hunt. In the place of bombastic music, that felt sound of machinery from the silent films can now be literally heard; the first scene of Testament, for example, takes place in a printing press, the roar of printers rocking the room and sounding like a train about to burst through the walls.The cluttered, cacophonous office makes an ideal hiding place for Hofmeister (Karl Meixner), a disgraced detective who inadvertently uncovered a mass conspiracy and now desperately attempts to evade capture until he can alert his superiors and redeem himself. As he hides, two goons come into the press, and without relying on the easy tension of escalating music, Lang lets dread creep in with a POV shot of one of the men spotting Hofmeister’s foot. But then the man makes no audible indication of knowing that the cop is in the room, and his careful silence gives the impression that he himself has prevented any music from being played, all the better to let Hofmeister believe he has not been seen.

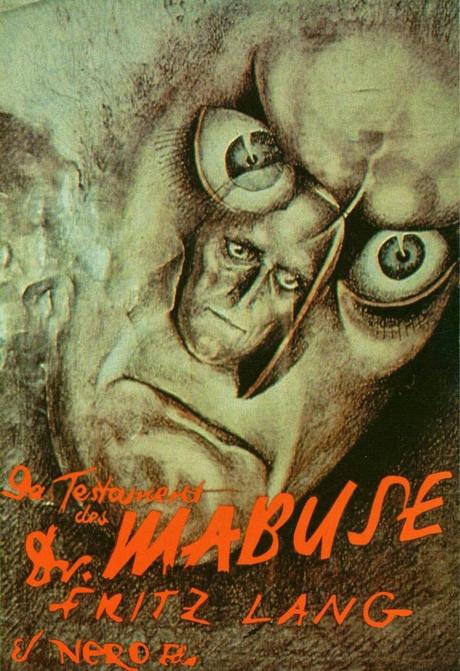

This opening foregrounds a sense of claustrophobia that pervades the film, a sense of the eponymous Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), now a catatonic husk in a mental institution robotically scribbling gibberish on paper, still exerting his hypnotic omniscience over everything and everyone. By now, it’s impossible to even consider the film outside the context of the Nazis’ rise to power, but the paranoia of the film and its hive-mind villains is unmissable as an allegory for blackshirted conformism and calculated disruption. Fleeing from the print shop, Hofmeister finds himself on an eerily empty street until harsh edits reveal people emerging, zombielike, from the darkness and advancing toward the detective. Later, as the action turns to follow Hofmeister’s old superior, Inspector Lohmann (Otto Wernicke), and reluctant gang member Thomas Kent (Gustav Diessl), that same hollow fear hangs over every too-quiet scene, an awareness that a small group of violent upsetters now exerts seemingly total control over everything.

Lang makes his critique more pointed when he contextualizes how such powers attain control. In an early scene of Professor Baum (Oscar Beregi Sr.) lecturing his psychology class on Mabuse’s crime spree in the previous decade, a tracking shot scans over the faces of his students looking as bored as possible hearing about pure evil. Viewing Mabuse’s case clinically, these academic undergraduates feel no sense of disgust toward him, thus making it easier for intellectuals to be swayed to the cause just as the ones who did not flee Germany eventually rallied around Hitler. Lang then takes this a step further by revealing that Baum has become obsessed with Mabuse’s writings, not only studying them but helping in their continued implementation.

Though it is hard not to see the parallels with Nazism today, the film nonetheless spends most of its time producing chills that focus the audience more on the moment than its implications. The film’s best sequence involves Kent, now resolved to break from Mabuse’s gang, trapped in the gang’s meeting room with his beloved Lilli (Wera Liessem) as a time bomb counts down to their demise. Cross-cutting between this scene and Lohmann raiding another apartment filled with Mabuse henchmen amps up the drama, but the material in the room is thrilling, with only the lovers’ increasingly panicked speech to “score” the scene as they improvise a way to survive. The scenario is so patently ridiculous and outsized for a movie that otherwise feels so cramped and tactile, but the editing and sparse sound design make the sequence unbearably gripping.

Less successful are the Mabuse apparitions that appear to haunt Baum, a throwback to Lang’s silent style that seems out of place in this rigidly spare, essentials-only direction. Nonetheless, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse stands as not only one of the bravest and most visible artistic reactions against Nazism from within Germany, but a foundational thriller, a pre-noir steeped in social fatalism and formal terror. Were it simply a political screed, the film might be nothing more than a footnote today. Instead, it belongs with the great movies, a social horror film that compels one’s complete attention even when nothing seems to be happening.