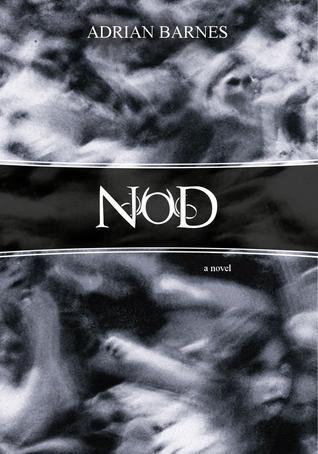

Nod, by Adrian Barnes

As I write this I have a fairly grim cold and haven’t slept properly in days. The result is I feel slightly distanced from the world, as if I’m seeing it through thick glass, and generally I feel rather disaffected and unpleasant. Normally I wouldn’t write a review when feeling like that, but in the case of Nod it seems almost fitting because this is after all a novel about an insomniac apocalypse.

Paul is a middling-successful writer. He specialises in unusual etymology, writing books about archaic or obscure words and their meanings. He lives with his wife Tanya in Vancouver. They have a decent and fairly typical life, not rich but doing ok. Then, one night, Paul goes to sleep and when he wakes up in the morning he finds Tanya irritable because she couldn’t sleep and the world irrevocably changed.

It soon becomes apparent that almost the entire human race had a night without sleep. Experts debate possible causes on rolling 24-hour news channels; people are frightened and cranky. It’s not until the second sleepless night that it starts to become obvious that what’s happening is effectively the end of the world.

A week without sleep and psychosis sets in. A month without sleep and you die. That’s not just in the book by the way; the exact timings may be off but we really do need sleep to maintain sanity and ultimately health. I’ve had a couple of nights with just my sleep being interrupted, and I already feel dreadful (it is just a cold though in case anyone is worried, I’ll be fine in a day or so).

Society starts to fray at the edges. Exhausted and desperate people start to turn on each other as they face a destruction that’s oddly intimate yet near-universal.

All the nicely-printed shelf tags had been pulled off and prices written directly on the goods in red felt pen. They were now roughly triple what they’d been two days ago. At least capitalism was still alive and functioning properly. The thought of that invisible hand still busily bitch-slapping the poor and desperate was almost reassuring. After all, in order to muster up the will to profiteer, one needs to be able to envision a future in which to spend one’s ill-gotten gains.

…Coming out of the store I saw that the line had now swelled to a couple of thousand panicky people who were surging forward against the line of soldiers. Something ugly was going to happen soon. An idea had to be growing in that massive line up: why pay when every defenseless person leaving the store with an armful of groceries is a sort of walking Food Bank?

What follows is an increasingly grim tale as everyone around Paul, including Tanya, falls into madness and terror. Those who still sleep get called “Sleepers” by those who can’t. They become the target of strange obsessions, schemes to somehow steal the secret of sleep from them, resentment and violence.

Paul is fixated on by a homeless man named Charles that he used to know. Charles has somehow got hold of Paul’s latest still-unpublished manuscript, titled Nod, and has found in it a meaning for the chaos the world is slipping into. Charles believes that Paul is a prophet, that his “Nod” manuscript is an explanation, and that he Charles is the high priest of the message Paul has brought the world. Soon others gather behind Charles’ message of salvation through lack of sleep. Tanya meanwhile starts to try to prepare for her own decline, while Paul steadfastly ignores the evident horror of their situation.

‘I think it’s time we started planning for what comes next.’ ‘Why don’t we just go to sleep?’ ‘I’m not going to sleep, Paul.’ I heard myself begin to whine. ‘You don’t know that. That’s just something out of a movie. Doomed people in movies always have this sad foreknowledge of what’s coming down the pike. But that’s just Hollywood bullshit melodrama. You don’t know you’re not going to sleep.’

Nod is not a novel to read if you require sympathetic protagonists. Paul is, quite simply, a self-absorbed misanthrope. For him the end of the world is inconvenient and dangerous, but he’s not going to miss humanity much. Even Tanya’s situation he sees more in terms of how it impacts him than what it means for her.

Everybody dies eventually. So if eight billion of us die in the next four weeks is that significant? All this sleeplessness plague could do was align those billions of inevitable deaths into a slightly narrower window of time—a matter of efficiency, not tragedy. If, during any one of a million previous nights, a giant asteroid had smashed the earth into gravel while we all slept, would it have mattered?

All of that makes his in some respects not the best viewpoint to see the end of the world from. Partly because I don’t think many readers will find themselves hoping Paul somehow survives, but much more importantly because his dispassionate attitude makes Nod a slightly bloodless affair at times (metaphorically speaking, literally there’s plenty of blood before the book’s done). If those I loved were facing insanity and death I’d fall apart. Paul adapts, and in doing so some of the trauma of what’s happening is perhaps lost.

Nod was also heavily criticised by some reviewers for its attitude to women. Where you have a single narrative voice it’s of course very difficult to distinguish between the character’s attitudes and the author’s, but it’s fair to say that there are problems here. I thought Tanya an interesting and credible character, but this is a narrative where she suffers sexual humiliation twice, is used by Charles to attack Paul’s self-esteem, and generally where she never seems to do anything but instead merely comments on what others do. She is acted upon, but never seems herself to act, and the same could probably be said for other women in the novel. Anyone who actually does anything, however crazed it might be, is a man.

The cruelty to Tanya may of course just be more evidence of Paul’s general selfishness and his solipsistic attitudes to the people around him. When he and Tanya take in a child who still sleeps so as to protect it from the mob, he comments: “We called her Zoe, Tanya having plucked the name from a mental list of future-children names that women seem to carry around inside themselves like eggs. Women. Eggs in their bodies, babies in their eyes.” It’s a strikingly sexist viewpoint, but whether it’s Paul being Paul or symptomatic of a wider issue in how the novel treats women is to some extent up for argument.

Where Nod works well then is its portrait of a descent into a nightmare-world populaced by crazed people who know in their lucid moments that they’re doomed but who even so act as if there’s some purpose to their frenzy. Where it works less well is Paul’s almost-indifference to the events around him and his objectification of Tanya which because his is the only voice we hear becomes the novel’s objectification of Tanya.

Hints of a wider pattern (and perhaps purpose) do emerge. Paul realises that those who sleep aren’t immune at all to whatever’s happening, but are just responding differently. He and the other adult Sleepers have the same dream of a great golden light, and the urge to sleep grows stronger and the sleeps themselves longer and deeper, raising the possibility that one day they may simply stop waking up. Children who can still sleep are stranger yet, no longer speaking and taking to the nearby woods where they form small silent communities.

Humanity then isn’t so much being ended as being altered, and the suspicion grew in me that the adult Sleepers like Paul only existed so that someone could protect the child Sleepers from the increasingly dangerous sleepless psychotics. I was reminded in fact of Michael Bishop’s The Quickening which touches on similar territory (though I’ve no reason to believe Barnes has read it). That’s of course a reading of the novel as story rather than allegory, and I think it’s fairly clear Barnes intends it to work as both.

Nod is what Margaret Atwood might call speculative fiction. This isn’t a novel about how or why all this is happening – nobody Paul meets has the faintest clue about either. Instead this is a novel about people and ideas. Charles’ creation of a religion around Paul is an attempt to wrest meaning from chaos, with Charles finding himself in the process transformed from an outcast to a leader. Paul finds himself on the receiving end of objectification, his own lack of faith in Charles’ credo an inconvenience. There’s nothing more dangerous to a new faith than an off-message messiah.

Perception and interpretation are key here. As people become increasingly gripped by hallucinations those who offer simple explanations of the world become dangerously attractive. In one scene a group watch the skies where they have collectively persuaded themselves they can see angels flying overhead, then someone suggests that in fact they’re demons and the crowd disintegrates in terror. Anyone who stands up offering certainty can form their own petty empire, granted power by people who’ve outsourced critical thinking. It’s hard not to see all that as a commentary on our own comfortably pre-apocalyptic world.

What underlines the arbitrariness of it all is a realisation Paul has relatively late. For him he’s at the center of it all, the new faith is formed around his word and everything that happens seems to be focused on him. He would think that though, because for Paul the world was always all about him.

It suddenly struck me that not everyone left alive even knew about Nod. Holy shit, I thought, almost no one knew about Nod. The vast majority of the Awakened were living in nameless kingdoms of their own terrified devising, and now they were ranged all around us, trembling and grinding their teeth.

Everything we read is in fact a tiny drama in a global ruin. Paul for a while sees his conflict with Charles as important, but it’s only important to them. His manuscript and the new faith it spawns are relevant to perhaps a few hundred people at most out of billions. What seems to him and Charles central to it all is in fact a side story, and perhaps there are only side stories.

That brings me back to Nod as commentary. Paul sees what happens to him as meaningful, but in the wider sense it plainly isn’t. Charles seizes power when the world falls apart, but it’s incredibly local power and he’ll still be dead within the month. The world of Nod is one filled with people with no sense of context, who think their struggles significant and their victories important but who in the blink of an eye will be lost in an ocean of endless incident.

In real life too we invest meaning in our dramas and our politics and of course we’re right to do so, a change of administration may make real differences to real lives, but step back a moment and most things that seem important either aren’t at all or are important just to us personally or locally, not on any wider level. We live amidst an epidemic of voices shouting at us from all sides, distracted by flickering images only a pixel deep,. Whatever signal there may be out there it quickly gets lost in the noise.

In the end, ironically or intentionally, Tanya has the right of it. She’s the only one who understands that what really matters isn’t the wider meaning and potential of the new world, but how it impacts her and Paul personally and their life together. It’s Tanya who sees that it’s important to protect Zoe, looking past her own descent into madness, degradation and death. Of course making Tanya’s concerns domestic is itself problematic from a gender politics perspective, save perhaps (only perhaps) for the fact that on this occasion she’s so plainly right.

Nod appeared on the 2013 Arthur C. Clarke award shortlist, where it was a controversial nominee due to what many saw as its deep-rooted sexism (and with some also just thinking it wasn’t very good). The objections to it were made if anything more pointed by the fact 2013 saw a male-only nominee list, which stood out given how many excellent female SF authors there are.

Unsurprisingly then, Nod was widely reviewed. I’d point particularly to this review by David Hebbelthwaite who is probably my go-to person for quality SF recommendations (and beyond, David doesn’t just read SF by any means). Also on the positive side is this review by Nina Allen, which I thought nicely captured the core allegory of the novel (“What Barnes seems to be saying, put most simply, is: ‘wake up!’”).

On the negative side I’d flag this review by the always perceptive Niall Harrison who absolutely slates the book in a single paragraph (“the reading experience is just limply unpleasant”) and this excellent review by Abigail Nussbaum. Abigail was I thought particularly good on the gender-issues of the book (though I disagree that the book has an incoherent cosmology, I think the lack of coherence is intentional and reflects Paul’s own limits as narrator and a wider point about the partiality of every perspective).

Filed under: Barnes, Adrian, Science Fiction Tagged: Adrian Barnes, Arthur C. Clarke Award