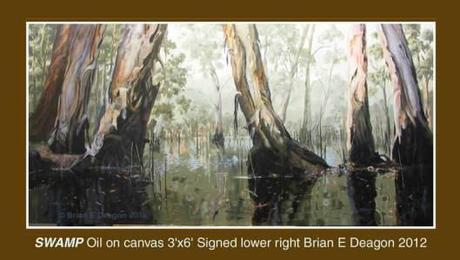

Swamp © Brian Deagon

Brian Deagon graciously hosted Ryan and me at his home and studio a few weekends ago, putting on a fabulous spread for lunch, giving us a tour of his sprawling bungalow and extensive shed studio and—most generous of all—a preview of his upcoming show in July. Both house and studio are set amongst gum trees through which the low light slings, projecting dramatic colours in the sky—oranges and lilacs—as the sun goes down. The shed studio is positively stuffed with paintings and flickering with moths and wasps. The maze-like house is lined with paintings like wallpaper. The dining room where we sat down to a huge crisp salad, a fresh baguette and some haloumi and cured meats has walls lined in gold-framed paintings—this is Brian’s personal joke about ‘art,’ and how one can tell whether the piece in question is art. His beautiful Swamp painting, a large piece, hangs outside on the wall by the front door, mostly sheltered from the weather, and apparently impervious to it. An old cane couch stands opposite it, and lounging about in it one can gaze at Swamp infinitely, wondering why it is that anyone spends their time in front of a television.

Brian has had a fascinating career thus far, and there’s something truly admirable in his approach to art, and plenty to be learned from it. He started out as an abstract painter, layering shapes and filling his paint with grit and sticking things to the canvas. One such painting stands on an easel in the shed, in two parts. Brian can’t remember how it goes together, and spends a few minutes rearranging it. He looks at it solemnly and says, ‘One night I stepped back and looked at this painting and said, “Brian, what are you doing? You’re only painting like this because you can’t draw.”’ So he gave up painting. He retired from his teaching job and took his daughter across the country and onwards to the US to pursue her promising ballet career. He stopped painting and he stopped drawing, because he recognised a crucial gap in his knowledge and could find no way to fill it. It was twenty years later when he heard of Lance Bressow that he returned to it, picking up right where he left off. There’s amazing courage in first giving up the thing that drives you, and then in returning to it and getting on with it. Yet Brian describes it as a straightforward enough thing, and one must simply do what one must do.

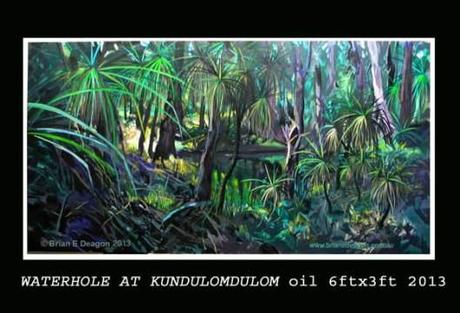

The works for Brian’s upcoming show at the RQAS are lush rainforest and swamp scenes, and I think to call them landscapes would be to neglect something important about them. These are not lovely false windows to hang on your wall, decorative pieces to remind one of the natural world beyond. One senses that these large paintings—at least a couple of metres across—are real portraits of real places, capturing the spirit of the places and recording the features. He alters things, certainly, for compositional harmony, but the places are recognisable, especially to his Aboriginal friends who know the places intimately. Brian’s work powerfully respects that sense of place, and it comes across so strongly that he has a profound sense of what it is to be in a place.

His paintings got me thinking about the idea of reverence and awe and a sort of secular experience of the sacred. It’s strange to me that the Western response to an expanse of landscape is that it’s a nice chunk of scenery, and that we can only experience the sacred through our own constructs. A forest is just a forest, possibly good for logging and mining, but a cathedral is the holiest of holies, and you’d better not bare your sinful shoulders that the Good Lord gave you. We worship ourselves rather than things bigger than us, and have no time for the so-called primitivism of the Aboriginal sense of sacred places.

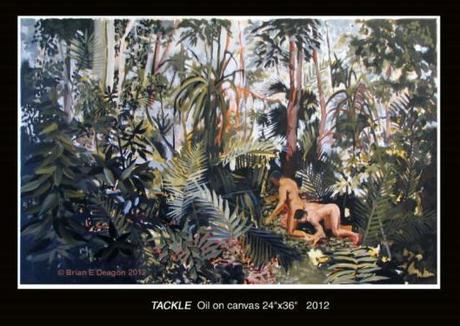

Tackle © Brian Deagon

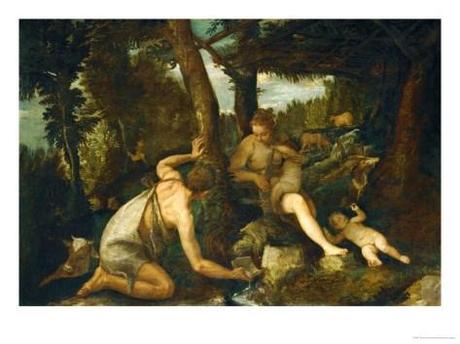

‘Little animals’ are beginning to make an appearance in Brian’s work, sprouting amongst the lush riots of greenery—tiny unclothed people wrestling. ‘We’re only little animals!’ he explains, chuckling a little. ‘We fight over food, territory or mates. Nothing else.’ When I return to the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna just a few weeks later I’m struck that Brian’s project echoes a beautiful painting by Paolo Veronese and his workshop, Adam and Eve after the expulsion from Paradise. Veronese’s forest is deep and shadowy, his trees falling to the edges of the painting as if they are at the edge of the earth. The canopy feels impenetrable, and hides all the animals—including some little human ones—in its darkness. There is a real wildness to this painting, a sense of having to tame something so untameable. Brian’s paintings tap into this same sort of wildness. Rather than cloaking his little human animals in the shadow of evil, he grows them out of the frenzy of vital colour. There is nothing shameful or sinful in Brian’s paintings, just a matter-of-fact appreciation of life.

Adam and Eve after the expulsion from paradise © Paolo Veronese

Some paintings Brian begins tonally, laying down a grisaille and introducing the electric colour later—phthaelo greens winning the day. One large canvas (and most of them are a couple of metres across) remains a grisaille, a dramatic, near nocturnal variation. Some of the smaller ones are painted without green paint at all, relying on yellow and black, and even red in places. Brian chuckles about the ability of the human eye to see red as green. He is immensely interested in what sort of trickery the painter can achieve.

Besides this, he is thoroughly playful in following his thought progressions. Another painting he has chopped into squares no bigger than a hand and framed each individually (in gold frames of course) to abstract them. He then repainted them, larger, on canvases that can be rearranged infinitely; an ultimate abstraction. He and Ryan discuss this idea of abstraction emerging from something representational, and of being excited by the abstract design inherent in found things.

Waterhole at Kundulomdulom © Brian Deagon

The most profound lesson is perhaps in Brian’s character: he is a man of immense humility, who has never stopped learning. He gladly takes classes with people much his junior, because he wants to learn from them. His extensive website—boasting a beautifully written collection of thoughtful essays—describes this best. He writes admiringly of Ryan, teacher at the Atelier Art Classes, after taking a class with him:

We really need to say more about what I see as Daffurn’s idealism. It’s not the kind where everyone has a “Greek” nose and all female breasts defy gravity in their perfect cones. It goes much deeper philosophically in a Kantian or Heideggerian sense. It comes from a reverence for the constructed body, and a profound understanding of its structure in three dimensions, and the fourth dimension being potential movement in time, and all within a space of light and colour, revealing and concealing the body at the same moment.

Nothing really needs to be invented, just deeply understood.

It’s a proud stance, underpinned by humility. Incidentally, the controlled art studio lighting is not mandatory, it’s just a help to the student. This is all based on a reverence for nature and the body we inhabit. More than that, it presupposes a profound belief in the intelligence of artist and audience, and the visual language they use. We intend to edify our viewer, not shock them. This might not be fashionable, but it’s not “dead” as some post-structuralists might claim. To invoke beauty, hope, intelligence, diligence, persistence, structure, design etc may be idealistic and even naïve, but its not wrong. Drawing of this kind is much more than a skill set or an arcane knowledge. It implies a moral relationship between artist and model.

I keep using the word “profound”. Because it is.

One could reflect this sentiment back on Brian, who, though for many years denied the technical education, is bold and audacious, but a humble student. There is a profound lesson in this.

See Brian’s show at the Royal Queensland Art Society, Petrie Terrace, Brisbane, 20 July to 3 August 2013. Don’t miss the ones in gold frames.