Men in suits love nothing more than to talk about how no one wears suits anymore. And it’s true that with each passing year, fewer and fewer people wear traditional tailored clothing. One retailer tells me that he mostly considers his necktie inventory part of his store decor these days, like bars that display antique liquor ads or currencies from exotic nations now defunct. But the reasons given by fashion writers for the decline of the coat-and-tie are often shortsighted, missing some of the more fundamental reasons why men’s style has continually gotten more casual. Since my own theory crosses paths with the reasons why we celebrate the Fourth of July in the US, so I thought I’d share it today.

Almost every story about the death of the suit starts in 1945, the end of the Second World War and roughly three decades before the suit would eventually wane. For Americans, the end of the war was a turning point in the 20th century, not only because it came nearly halfway through, but because the war revolutionized America’s role in global affairs. The US shaped the new post-war order with organizations such as the UN and NATO, which together with American diplomacy and military strength gave rise to the Pax Americana. America emerged from the Second World War as the only power virtually undamaged, its vast military and economic capabilities fully intact, and the only country with nuclear weapons. American power was at its height.

For American men who loved tailored clothing, however, the apogee of the 20th century was a little earlier, in the 1920s or 1930s – the Golden Age of Hollywood, the well-dressed set, and the coming of age of classic American Style. The post-war period, on the other hand, was fractious, confused, and noisy. Sportswear thrived. Ready-to-wear proliferated. Designers eventually replaced tailors. This revolution in menswear coincided and overlapped with the culture wars of the 1950s and ‘60s. Establishment types wore the suit; anti-establishment types took to white tees, leather jacket, and jeans. That shift towards what Bruce Boyer calls “rebel clothing” was the first meaningful move away from the coat-and-tie. The suit has been trying to wash itself clean of the stench of Establishment ever since, never with complete success.

There are dozens of other theories on why the suit has died, ones that are often less convincing and more cantankerous. Some say people are lazy and lack personal pride. Others say the availability of cheap clothing has crowded out the market for quality tailoring. The worst takes are the ones that link the decline of tailoring to Western civilization itself – as the suit has declined, so has morality and virtue. These are about as bad as people who base their conception of the 1950s off film noir.

The decline of the suit is about more than post-war trends, however. To truly understand it, we have to start not in 1945, but the 17th century at the birth of liberalism. By liberalism, I don’t mean leftist politics or Hillary Clinton (please don’t send me annoying emails about Hillary Clinton). I mean the philosophy that gave us inalienable rights. Liberalism is perhaps best summed up in the rallying cry of the French Revolution, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” Or the single phrase of the American Revolution with the greatest continuing importance, that all men are born equal and free. (Before we move on, let me beg you one more time not to email me about Hillary Clinton.)

Liberalism didn’t come out as a seamless garment. Many of its original thinkers were deeply divided on important issues; some of these divisions continue to this day. Philosophers have wrestled with some of liberalism’s inherent contradictions, as well as argued over the different ways we can value both liberty and equality. But liberals are united on certain values – the potential for a rational society and the inherent dignity of all people. Isaiah Berlin beautifully sums it up in an essay on the topic:

What they had in common was the belief that men were by nature, if not good, at any rate not bad, potentially benevolent, and that each man was the best expert on his own interests and his own values, when he was not being bamboozled by knaves or fools; that on the whole men were prone to follow the rules of conduct which their own understanding suggested to them. Most thinkers of the eighteenth century believed that progress was desirable – that is to say, for example, that freedom is better than slavery, that legislation founded on what was called ‘the precepts of nature’ could right almost every wrong; that nature was the only reason in action, and its workings, therefore, could in principle be deduced from a set of axioms like those of a theory of geometry or physics, if you only knew them.

It’s difficult to appreciate the power of these ideas today, when they seem self-evident and ubiquitous. It was not always thus. Joseph de Maistre’s Considerations on France comes from a time when liberalism was still a radical system of beliefs.

Maistre was one of the fiercest critics of the French Revolution. He argued against a French Republic and instead for a new alliance between throne and alter under a restored Bourbon monarchy. As he saw it, democracy would bring terror, violence, and mob rule. The world was “red in tooth and claw, a vast scene of carnage and destruction,” and man is “by nature vicious, wicked, cowardly, and bad.” The only way out of this Hobbesian world was to respect monarchy, God, and tradition. Emile Faguet described Maistre as “a fierce absolutist, a furious theocrat, an intransigent legitimist, apostle of a monstrous trinity composed of Pope, King, and Hangman, always and everywhere a champion of the hardest, narrowest, and most inflexible dogmatism, a dark figure out of the Middle Ages.” As Berlin notes, Maistre’s Considerations on France is more “interesting and outré than important,” but it represents the last dying gasp to defend feudalism against the march of progress.

OK, but what does this have to do with men’s suits? To see the influence of liberalism on clothes, look at how Queen Elizabeth I dressed in the late 1500s, just before the birth of liberalism. Pictured above is one of her typical get-ups (maybe among the more modest of her 1,300 dresses). Elizabeth was known for using dresses like this to create an image of power and majesty. She was a woman in a man’s world and had big shoes to fill. As the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, the king’s second wife, some in Elizabeth’s family saw her as illegitimate.

To strengthen her precarious position, Elizabeth wore grand dresses made from precious silks and jewels, sometimes trimmed with white pearls to symbolize her purity and virginity. Whalebones were used to contort her body. It took her staff over two hours each day just to dress her. The point of all this was to create an otherworldly image and convey a powerful, imposing presence, which helped legitimize both her role on the throne and the institution of monarchy itself.

This intentional use of clothing as a talisman of power is more obvious when you look at the Parliamentary act at the time regulating clothes. In the 16th century, if you wanted to wear gold, you had to be of a certain status. If you wanted to wear fur, you had to be worth at least 100 pounds. If you wanted to wear a silk nightcap when you slept, you had to be worth at least 20 pounds. The Queen both sat at the top of this hierarchy and enforced its every stipulation. Powerful people wore certain clothes, and the clothes in part helped to legitimize their power.

Things changed by the time the House of Stuart came along in the 1600s. The monarchy was less respected, partly because of an earlier Parliamentary inquiry into the royal wardrobe, which revealed that money had been siphoned off and used on unauthorized days out and other jollies. The royals at this time were seen as clumsy and corrupt, excessive and vice-loving. Satirical representations of them in ridiculous clothes were distributed around England. Negative comments about clothes eventually led to rebellion, and Charles I was brought to London for trial (to make matters worse, Charles ordered a velvet suit covered in gold embroidery for his hearing). And when he was led out for execution, he put on two shirts so that he wouldn’t shiver, which he worried some might mistake for shuddering from fear (this is possibly why Steve Bannon wears two shirts, but I haven’t confirmed). After his head was separated from his two collars, England was without a monarch for the first time in 1,000 years.

British leaders were never quite so arrogantly extravagant after that. Oliver Cromwell, who led the country’s Commonwealth, asked for his portrait to be painted “with warts and all,” departing from the Elizabethan strategy to look otherworldly. Charles II opted to wear a more modest coat with his britches, instead of the traditional and more ornate doublet. Queen Victoria, who was very much interested in clothes, understood the importance of looking modest. In a letter to her son, Edward VII, she once wrote:

It’s the one outward sign from where people can and do judge the inward state of mind of a person. It’s of particular importance of persons high rank. we do expect that that you will never wear anything extravagant or slang, not because we don’t like it, but because it would prove a want of self-respect and be an offense against decency, leading — as it has often done before in others — to an indifference in what is morally wrong.

There were some hiccups along the way – George IV shocked English citizens by leaving behind a wardrobe that was auctioned off for a kingly sum – but after the beheading of Charles I, the British monarchy learned that, in order to maintain power, they would have to at least give some deference to the people and to humility. Divine right alone no longer justified monarchy. With the rise of liberalism and democracy, royal dress had to be more modest, or at least signal certain puritan values.

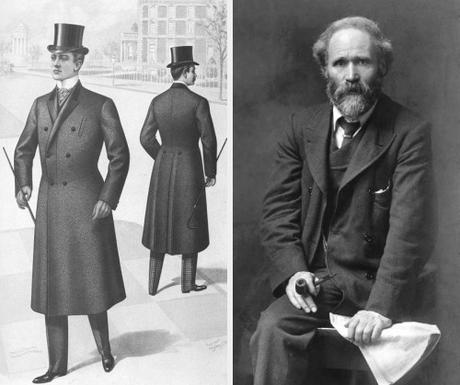

This story is more than about monarchy – it’s about the general shift towards modest and relatable clothes with each passing generation. When Kier Hardy, founder of the British Labour party, first took his seat as a Member of Parliament in the late 1800s, he wore a tweed suit, red tie, and deerstalker cap. Hardy was a socialist who was elected to represent a working class area of London. The accepted parliamentary uniform at the time was more formal. A proper gentleman at the time wore a black frock coat, black silk top hat, and firmly starched wing collar. The press was so scandalized by Hardy’s working man clothes that they wrote, “a cloth cap in Parliament!”

Today, the royals mostly wear clothes that are almost indistinguishable from what everyone else wears. Prince Henry and William are often photographed in business casual; the Duchess Kate Middleton wears Supergas (what the The Times called middle-class mom shoes). They wear special clothes for certain events, but it’s not unusual to see them or other world leaders forgo a tie, even when they appear at political gatherings.

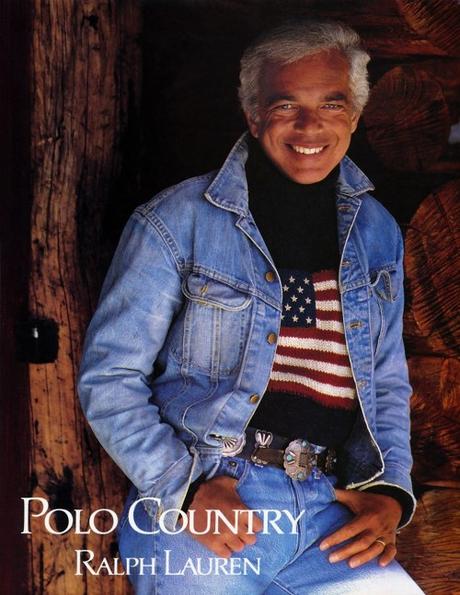

The last four hundred years of fashion follows this same broadening and flattening of dress codes. The Duke of Windsor’s father chastised him for wearing gray glen check suits and turn-ups when inspecting troops – something that today would be standard business attire, but at the time was considered country wear. Vincenzo Attolini at The London House made Neapolitan style famous by taking out all the stiff and formal structure in tailoring. The most liberal country of all, the United States, has always championed a more informal look. Almost every important American innovation in fashion has slightly moved international wardrobes towards casualwear – the lounge suit as day wear; the single breasted two-piece suit; patchwork madras, seersucker, and the button-down collar; the penny and tassel loafer; belted trousers; five-pocket jeans, white t-shirts, and the rebel look; 60/ 40 mountain parkas, Champion sweats, and Rugged Ivy; repurposing sportswear as everyday attire; and, of course, Western wear.

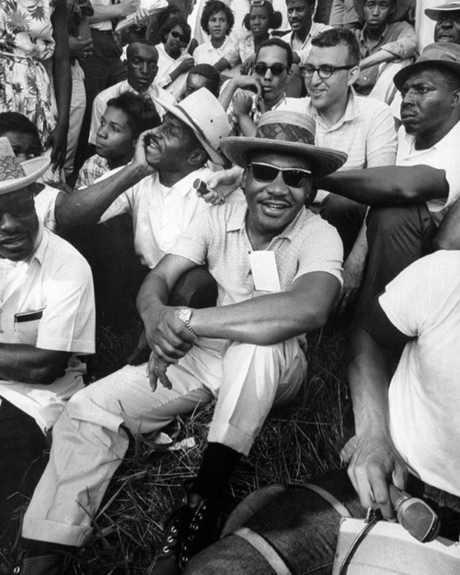

These changes in fashion support the general democratic, liberal ethos of our age to be more inclusive, to grant more individual freedom, and to celebrate the common man. It’s easy to be cranky about the death of suits – and probably telling that some who worship the suit also harbor illiberal attitudes about other things – but the decline of the suit has been accompanied by the freedoms we all enjoy. It’s hard to imagine that men and women could have achieved the last fifty years of progress on gender and sexual equality while wearing the two-piece suits and sundresses of the ‘50s. Ideas about the fluidity of gender and sexual identity today are also deeply tied to clothing choices.

What do we lose? Less confusing business dress codes; better looking scenes inside nice restaurants and hotel bars. Suits and sport coats have also gotten more expensive over the years as quality tailoring becomes rarer. And it’s a daily struggle to dress well without someone asking you why you’re so dressed up. All of these are annoying, but they’re small price to pay for more personal freedom for everyone.

The fashion industry is often criticized when it repackages working class clothes as upscale items. Ben Roazen wrote a piece for Hypebeast last year that called out Golden Goose for being crass and classist for selling luxury versions of “pre-distressed sneakers that imitate the look of game-worn basketball sneakers and shredded skate-shoes.” But celebrating “low brow” aesthetics isn’t classist, it’s part of a 400 year history that inverts classism. The expansion of democratic power is inextricably linked to how much we celebrate working class people and their aesthetics. The grossest classism is when people think only “upper class” aesthetics are justifiably expensive or worth wearing.

It’s a shame that it’s harder and harder to wear a suit and tie these days, but you can still get away with more casual forms of tailoring if you’re willing to look a bit more dressed up than most. And on balance, the world has gotten better with each passing generation, even if they’re dressed more casually. That’s the kind of optimism and democratic ethos that I think defines the better parts of America. Happy Fourth of July.