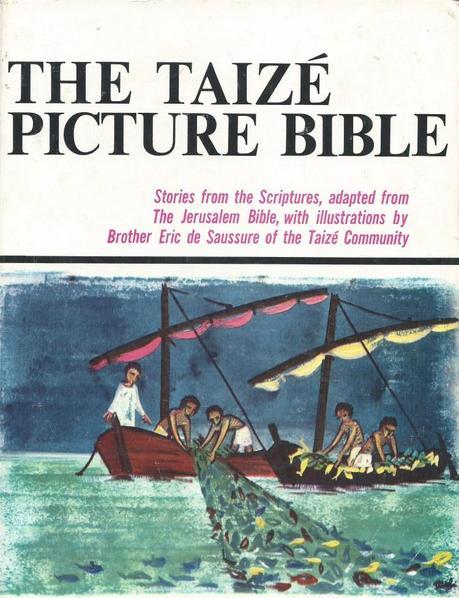

There is an appealing, almost haunting spareness to the Taize Picture Bible (1968) in both word and text. Published in the USA by Fortress Press (mine is a fourth edition, 1978), the “note to readers” says

“The guiding editorial policy in this adaptation has been to facilitate understanding by readers of many age levels while remaining faithful to the words and meaning of the Biblical text.”

There is nothing prettified or cutesy about the images or the storytelling in this book. In fact there’s very little that makes it a children’s Bible at all except the stunning illustrations, which, frankly, I, as an adult, find help me move more deeply into the story.

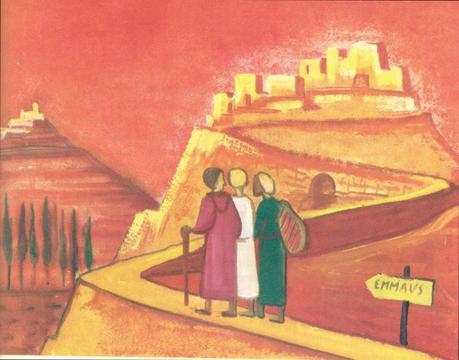

on the road to Emmaus

I’m not an expert in children’s Bible’s–of those in print I generally like The Jesus Storybook Bible, although it is a bit twee at times in both word and image–but some of our precious suitcase space went to bringing the Taize Picture Bible with us, perhaps for the same reason that Taize music is some of the only worship music that never makes me feel sick to the stomach.

I don’t feel like it is manipulating me or conning me into feeling emotions I don’t feel or thoughts I don’t think. I don’t feel like it’s trying to do anything except reflect the strange beauty of God. In a world where it feels like everyone is trying to sell something–even “right” doctrine and the “right” perspective are items for sale–this is a profound relief.

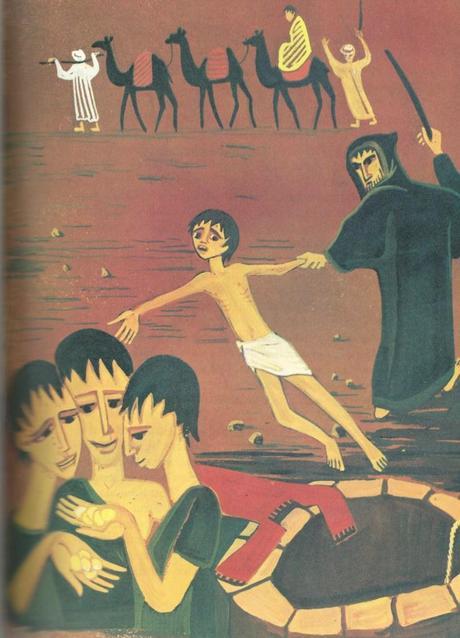

It seems to me there is value in offering some of the Bible to children in all of its unvarnished strangeness, perhaps for a similar reason that Grimm’s fairy tales in all their grimness are read to children in Waldorf schools:

“Although many of the [word-]images in these stories are ‘grim,’ many experienced teachers believe that the inner pictures the children form are only as vivid or harsh as they can handle. The value of these stories is thought to be in their power to stimulate the child’s imagination by bringing archetypal images. It seems fitting that the range of these images should be as full as possible, since each strengthens the child for certain challenges he or she may face during life. I chose not to alter any of the stories when I told them. If I was not comfortable with a story in its entirety, I did not tell it at all.”

“The style of storytelling that I prefer is when the storyteller does very little with voice or movement to dramatize the story. The goal is to let the images of the story speak within the child’s imagination.“

(David Darcy at Waldorf Without Walls)

Joseph sold by his brothers

“In the art and fantasy of fairy tales lies a very deep wisdom which has power to awaken children from the sleep of ordinary life. Forces of healing are also hidden in each fairy tale. The most important effect of the fairy tale is that they stimulate the feeling that man is a being of development, of struggle, of metamorphosis, and that behind all the adverse forces of giants and dwarfs, witches and demons there lies the good world of the true genius of man.”

“Children experience the greed of the wolf and the evil of the witch quite differently than we adults do. They experience these qualities more as archetypal pictures about life, but do not yet identify themselves personally with the suffering. They trust that there will be a happy ending or that good will triumph over evil.”

(Fairy Tales: Healing Food for the Child’s Soul)

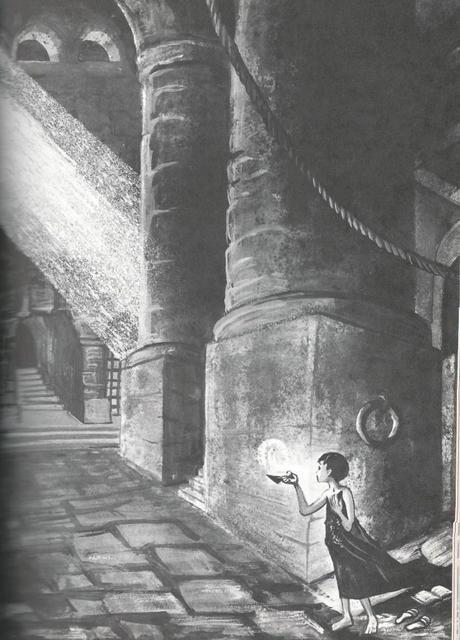

God Calls Samuel

And now you may be wondering why I am citing the imagination-enhancing power of fairy tale when we began by talking about the Bible, which for many people has less to do with imagination (so we think) than belief:

“In Mere Christianity, C.S. Lewis wrote that to pretend helps one to experience God as real. In “Narnia” he offered a way to pretend — by depicting a God who is so explicitly not a God from an ordinary human church. Aslan keeps God safe from human clumsiness and error.”

Safe? Of course the Bible is not safe for children. Which is not the same thing as saying parts of it are not good for children.

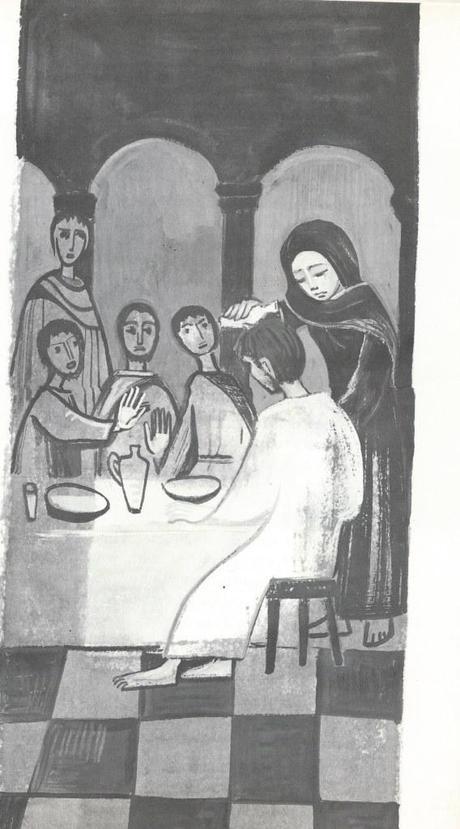

anointing at Bethany

“What does it mean that our society places such a premium on fantasy and imagination? ‘No culture,’ observes the child psychologist Suzanne Gaskins, ‘comes close to the level of resources for play provided by middle-class Euro-American parents.’ In many traditional societies, children play by imitating adults. They pretend to cook, marry, plant, fish, hunt.”

“Observing the lack of fantasy play among the Manus children in New Guinea, Margaret Mead noted that ‘the great majority of children will not even imagine bears under the bed unless the adult provides the bear.’”

“[Fictions] help us to learn what we find emotionally true in the face of irreconcilable contradictions. That is what Joshua Landy, a professor of French literature, argues in How to Do Things with Fictions: fiction teaches us how to think about what we take to be true. In the cacophony of an information-soaked age, we need it.”