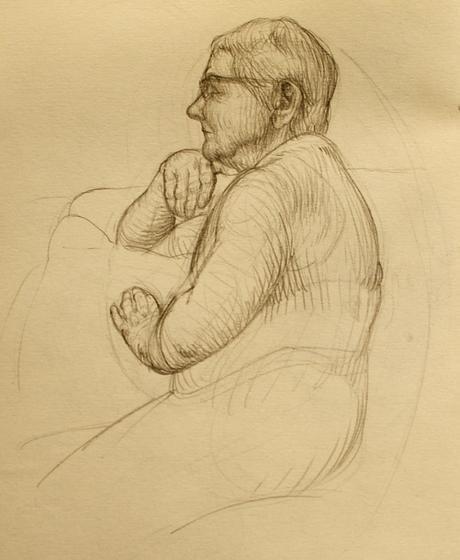

Dr Rhyl Hinwood, drawn from life

Dr Rhyl Hinwood is a part of the fabric of Brisbane. Her work wove through my life well before I heard her name; her social spirit created Brisbane institutions that have profoundly shaped my life. Eminently at home here, and deeply invested in our sprawling, sun-drenched city, her life’s work exists not just in the immovable sandstone she carves with her gnarled hands, but also in the people of Brisbane. For while Rhyl loves to shape stone, and her hands have formed memorable parts of the city’s surface, she cares just as deeply about shaping less tangible things.

Steele building, University of Queensland

I learned this when Rhyl and her husband Rob welcomed Ryan and me into the home they built with their own hands some fifty years hence, Ryan eager to paint her portrait. The house is full of personality, and full of Australia. The sloped wooden roof hangs high above the tiled terracotta floor, and the space in between is decked with gumnuts, dried leaves, wicker chairs, exuberantly patterned fabrics and rugs in earthy colours and, of course, endless bronzes. A carved wooden cabinet houses the radio which plays classical music as we work, and on top sit a glowing cluster of green-bronze busts—mostly the heads of Rhyl’s grandchildren, and one of her mother. Frog bronzes pipe at flutes and saxophones as though an Australian rainforest bacchanal procession were coursing through the house.

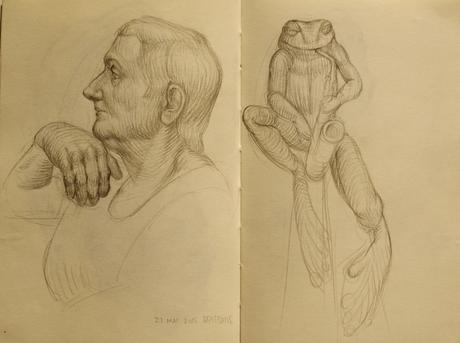

Dr Rhyl Hinwood (from life); copy after her sculpture

Rhyl is possibly best known for her work at the University of Queensland, where I studied, where she got her break carving grotesques for the central quadrangle, the Great Court. This was the beginning of a continuing relationship with the university, with the various colleges commissioning large sandstone works from her to this day, and, of course, the Wordsmiths Café (where I served many a coffee) and its snaking literary tribute to Australian authors. Rhyl assumes her position on the couch for Ryan’s portrait and talks about her recent visit to St Leo’s college, whose gate she recently produced, and where she was subsequently invited to attend a formal dinner and see all the boys suited up for an opera performance. Her attendance is always welcome, and she always follows through—being present, she advises us, is always a good strategy. When you are out in the community, being seen, meeting people, things come up, work comes in. She brims with stories of concerts, Great Court races, bumping into the now fully-grown son of a man she met while carving at UQ decades ago; the governor taking a liking to her and wanting to chat endlessly; the lovely but reserved Canadian woman she met and introduced to university dignitaries with the ease of an equal; the English reverend who saw her working in the Great Court and who invited her to stay with him in England in the very town where she was coincidentally going to work on a church. Rhyl excels because she is endlessly open and interested in her fellow human beings.

Wordsmiths Cafe, University of Queensland

Rhyl is a storyteller, and at heart, her art form, public sculpture, is about collecting, distilling and preserving stories. Her frankness and clarity are indispensable in this matter. One afternoon we tramp down into the backyard to see some of her works in progress, and her storytelling weaves effortlessly in and out of the imagery. A huge concrete semi-circle bounds her outdoor carving area, a moveable crane fixed to the top, and a starfish adorns it. Heavy power tools rest nearby. Rhyl is working on an arced piece with a little saint, and Ryan’s narrow face is her inspiration for the character—she would hate for her sculptures to be peopled with generic forms. We follow her down a little path through the rainforest garden to the studio. It is a multi-level affair, wooden, again with a dramatically sloping roof. She shows us some plates she is preparing for bronzes, an amalgam of wood and plastic. She traces the elements of each one with her hands, explaining the stories through simple yet eloquent symbols.

Wordsmiths Cafe, University of Queensland

Over several weeks we sat by her fireplace (flanked in sandstone, decked in coral, shells and urns full of banksias and gumnuts), painted and drew, and shared meals. Her husband, Rob, once in the army, but also a builder and a leather worker and ceramicist, chimed in with jokes and stories, and as the weeks went by, their stories built up a tapestry of their rich and social lives, their children, their travels, their work, their Brisbane. Rhyl’s parents had a house by Yerongpilly, and Sunday afternoons when she was young they would open their doors to Asian students, and together they would spend the evening dining and dancing on the veranda. She and her parents fundraised to construct International House at the University of Queensland, a residential college that operated on the same welcoming principle (‘that brotherhood may prevail’), the residential college I myself called home for two years and through which I made many lasting friendships that span the globe.

Forgan Smith building, University of Queensland

Paring a story back to the core elements requires much conversation, and asking many questions. Rhyl recalled seeing the austere slogan above the Forgan Smith building at UQ, home to my beloved philosophy department: ‘GREAT IS TRUTH AND MIGHTY ABOVE ALL THINGS,’ and resolving to work around this proclamation. She asked many professors, ‘Do you think that truth is the purpose of the university?’ and was met with a resounding no. After much conversation and deliberation, she determined that the university must, in fact, stand for knowledge: the uncovering of, collecting of, and preserving of. Her research efforts are admirable: she showed us a photograph of a large symbolic piece in the midst of being installed in a college in Sydney. She told us of an ineffectual meeting with all of the stakeholders, in which dominant personalities drove the discussion, and each party felt compelled to have their stamp. Earthy, pragmatic Rhyl simply decided to meet personally with every individual involved, and to give each their chance to speak with her one on one. Having collected every viewpoint, a plan for the piece evolved in her mind, and when she presented it to the group every party was satisfied. There is a profound lesson in this humble, attentive method of collecting stories and compiling them into something fitting and meaningful.

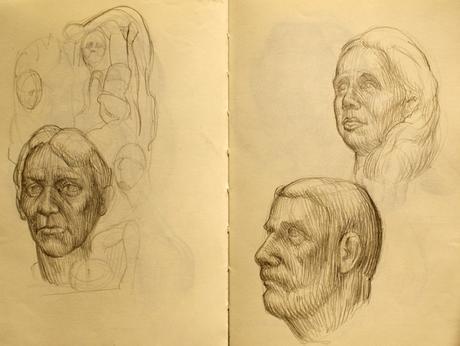

Copies after Rhyl Hinwood

Societies and social events can be very demanding on your time, Rhyl admits, but she urges us to be present in our cities, in our communities. A chance meeting at a symposium, a fortunate conversation over morning tea at Customs House, can open up surprising opportunities. And one suspects that finding one’s place in one’s community and building it over a lifetime comes with rewards far deeper and richer than public commissions. Rhyl Hinwood lives and breathes Brisbane, and can take satisfaction in the knowledge that she and her work are an enduring part of its story.

Wordsmiths Cafe, University of Queensland