Tonight we will experience a change of seasons: the occurrence of the vernal equinox, which marks the official start of spring. In fact, it will be quite a promising event. The earliest the equinox has occurred nationwide has been 128 years. More about that later.

At the equinox, the Earth will have reached the point in its orbit where its axis is perpendicular to a line from the sun. So the sun will then be directly over a specific point on the Earth's equator and move north. In the sky, the ecliptic and the celestial equator cross each other.

Moreover, it will appear as if the sun rises exactly in the east and sets exactly in the west. It is said that daylight and darkness are in the right proportion and that the sun's rays span the poles. The sun spends half the day above the horizon and half the day below the horizon - but that statement ignores the effect of Earth's atmosphere, which bends the sun's rays (called refraction) around the Earth's curvature as the sun is close to the horizon. But because of this deflection of the sun's rays, the sun's disk is always seen slightly higher above the horizon than it actually is.

Related: What is an equinox?

When you see the sun appear on the horizon, you are actually looking at one optical illusion; the sun is actually at that moment below the horizon. So we get a few extra minutes of daylight at the beginning of the day and a few extra minutes at the end.

The supposed equality of day and night gives us the Latin name 'equinox', which actually means 'equal night'. But in reality, thanks to our atmosphere, the day is longer than the night during the equinox. For example, at the latitude of New York, day and night are approximately equal, a few days before the equinox, on St. Patrick's Day, March 17.

Sun over New Guinea

Astronomers can calculate the moment of the vernal equinox to the nearest second. This year it will take place on Tuesday, March 19 at 11:06:20 PM EDT. At that time, the sun appears directly over the equatorial Pacific Ocean, northeast of West Papua, New Guinea, and about 63 miles (101 km) south of Mapia Atoll, historically known as the Freewill Islands or San David. In the days that follow, the direct rays of the sun will continue to migrate north of the equator and the length of daylight in the Northern Hemisphere will appear to increase accordingly.

Why so early?

As previously noted, this will be the earliest spring equinox in the contiguous United States in 128 years. There are two specific reasons for this:

1) The four-yearly occurrence of a leap year often causes a small variation in the date.

2) Daylight Saving Time (DST)

When a leap year set us back a day

First, the fact that 2024 is a leap year not the reason for the early arrival of this year's equinox. Rather, it is the leap year we observed in the year 2000.

Let's look at the dates and times of the equinoxes leading up to 2000. Note that the equinox occurs about six hours (or a quarter day) later in the calendar each year:

Now, in 46 BC, Julius Caesar's consulting astronomer, Sosigenes, knew from Egyptian experience that the solar year was approximately 365.25 days long. To take into account that remaining quarter of a day, an extra day - leap day - was added to the calendar every four years. Unfortunately, the new Julian calendar lasted 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than the actual solar year. By the year 1582, thanks to the overcompensation of observing too many leap years, the calendar was a total of ten days out of sync with the solar year.

It was then that Pope Gregory First, to make up for matters, ten days after October 4, 1582 were omitted, making the next day October 15. Then, to better correspond to the length of the solar year, century years, which in the old Julian calendar would have been leap years, were not. The exceptions were the century years that were divisible by 400. Therefore, 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not leap years.

But 2000 was a century year, divisible by 400, so it was considered a leap year. If we had skipped the leap year in 2000 (as was the case in 1900), the equinox would have started on March 21 at 2:35 a.m. EST.

That is why we have placed an asterisk

next to that date. So thanks to the fact that February in 2000 had an extra day, the date of the equinox relapsed one day

until March 20.

Daylight time is postponed on the March 19 equinox in East And because the surplus added to 365 is not exactly a quarter of a day (.2500), but a little less than a quarter (.2422), the occurrence of the equinox comes about. 47 minutes earlier

March 19, 2024 11:06 PM EDT

The asterisk indicates that we were now observing daylight saving time that began in early March... a practice that began in 2007. In 2000, only those in the Pacific Time Zone observed the equinox on March 19. In 2004, 2008 and 2012, those in the Pacific and Mountain Time Zones observed spring breaking on the 19th.

In 2016, those in the Central Time Zone celebrated the arrival of spring on March 19. Had we still been on the old system (when daylight saving time didn't start until early April), we would have been on standard time in 2016 and Easterners would also have observed the equinox on the 19th (at 11:30 PM) ... but daylight Time has postponed that for another four years. Finally, in 2020, from coast to coast, spring arrived on March 19, and it will in 2024 as well.

And just for context, in 1896 the spring equinox arrived on March 19 at 9:29 PM EST.

Astronomical vs. meteorological spring

RELATED STORIES: -

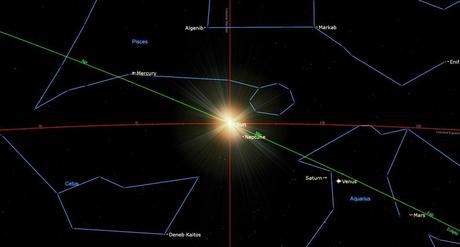

The brightest planets in March's night sky: How to see them (and when)

- Night sky, March 2024: what you can see tonight

- What the spring equinox looks like from space

To be honest, there are actually two sources: the astronomical spring and the meteorological spring. Astronomical spring is measured by the vernal equinox, but that is only a marker in the great flow of time set up by man; a sidereal milestone. Accurate as a ticking clock, but only approximately the timing of the seasons. Meteorological

Spring would have already started on March 1 and lasted until the end of May. In reality, however, meteorological spring ignores the clock and the calendar, makes its own rules and creates a festival of song and blossom, all in its own time.

The crocuses, early robins and other spring phenomena pay no attention to the hair-splitting details that mark the astronomical arrival of the spring equinox. They all have their own way of knowing when spring really starts. Joe Rao is an instructor and guest lecturer in New YorkHayden Planetarium . He prescribes on astronomyNatural history magazine the Farmer's almanac