Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca,

Lecturer in History of Contemporary Philosophy,

Universidad de Madrid (UNED), Spain

She got out of her car, knees together, showing off her elegant high-heel shoes, her skirt cut and her printed silk blouse with a cleavage that left the smooth skin of her neck in full view. This image of Isabelle merged with the other images that were still in my memory, jumping around and crashing into one another over and over again, obstructing the truth and pulling me towards that world of memories previously alive, idealized or simply made up. It was getting dark outside and I was about to reach Sils Maria, in the Swiss High Engadin, to take part in a congress on Nietzschean philosophy, together with a high-level international group of experts.

Her weightless, ethereal hair in the wind and her big blue eyes were the hallmarks of this free and modern woman, someone who moves with independence and who knows how to get the most out of life. At the same time, though, she enjoyed an elevated philosophical and intellectual reputation which inspired admiration in students and teachers alike. It’s impossible to reach the levels of understanding of the difficult topics she has written about without some kind of rigorous asceticism, and her academic career was a testament to her courage and self-discipline. Nonetheless, and in contrast to this, she was also well-known for her desire for fun, for her girl-about-town attitude, and for her ability to mix smoothly with the shadows of the night where, together with all the luxury and glamour, one also finds touches of the banal, the frivolous and, yes, the obscure.

Although this wasn’t the first time she was visiting this incredible location in the Swiss Alps, the landscape of the valley and the sublime mountains made an impression on her once again, to the point where she was naming the peaks to me one by one. On the Northern side, Lagrev and Gravasalna, and to the South, Rosatsch, Corvatsch and Chapütschin. And then of course the lakes: the Campfer, Silvaplana and the Sils, its waters shifting between sapphire blue and turquoise. The colours varied between the light green of the meadows at the base, to the darker green of the great woody masses on the sides of the valley, to the gray of the peaks and the white at the very top, the colours morphing from one to another with magical fluidity: within an hour they would go from the joy of the sunny brightness to the severity of the greyish fog and mist. Among that deep silence, one had the impression of witnessing the birth of the world, since neither the grass nor the earth nor the water seemed to have grown old at all.

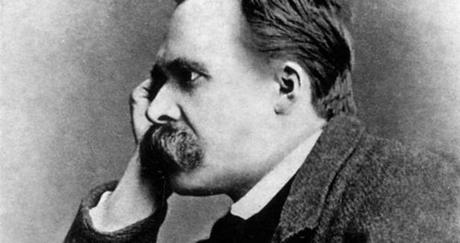

Isabelle remembered that during the summers that Nietzsche spent there, between 1881 and 1888, he lived in a rustic lodging that was part of a small group of houses on the valley-side, with balconies full of flowers. After some time, the original village had become a place of luxury for affluent holiday-makers. “Nietzsche”, she would tell me, “would come here to think and to write. He would work in the mornings, take a stroll during the day, and return in the evening with his notebooks full of notes, only to resume working after dinner until well into the night. According to his journals, the strolls he most enjoyed among the many that he took (through the woods, along the shores of the lakes, in the mountains, etc.) were the ones that took him up towards the lookout point, from where one can contemplate the solitary Surlej, lying among the meadows; or even when he went up until he reached the throat of the Fex from where, to the right of Platta, it is possible to view the entire amphitheater of peaks. How about we go on these strolls ourselves today?”

The congress’ first talk was given by a veteran Italian professor who read out the content of a letter by Nietzsche to his friend Peter Gast from August 1881, in which he wrote, “Here in Sils Maria the most unexpected thoughts strike me. My dear friend! Sometimes I get this strange feeling that I’m one of these machines that explodes. The depth of my emotions makes me shiver and laugh. Sometimes I can’t leave my bedroom simply because my eyes are all red. Why are they so red? Because the previous day, while I was strolling, I had cried too much, not with sadness but with joy. I was singing, I was talking nonsense, I felt full of life again, a feeling I now treasure in myself as others seem to lack it”. It was obvious, the speaker was adding, that Nietzsche needed solitude. He would arrive here full of work projects, only to find his trunks full of books sent to him by his loyal friend Overbeck from Basilea. Here he read Spinoza,and was surprised by the proximity he felt towards him; he dabbled in mechanics, political economy, cosmology, biology and psychology. A great transformation was growing inside of him, and for it to bear fruits he vitally needed solitude. He was fond of saying that he came here to “disappear forever” (der auf ewig Abhandengekommene). But the most important reason was, in fact, that in Sils Maria he could take long strolls and seek out inspiration, because to him — and so he mentions explicitly on more than occasion — his best ideas would come to him when he was climbing the mountain.

Another speaker referred to the inspiration that Nietzsche confessed to have had in Sils Maria that led to his more decisive thought, his most enigmatic and difficult. While taking a walk near the huge monolithic block of the Surlej, a vision came to him, making him shiver and write in his journal: “This was written at 6,000 feet above the rest of men, and in the present time.” What had he seen in this ecstasy, and what was this note hiding?”, the speaker was wondering. From what he told us later, in Ecce Homo, in this vision that had divinely exalted his soul, he thought that he had suddenly grasped the law of the worlds, their eternal return, in a kind of Heraclitean or Pythagorean reminiscence. A very old thought, suddenly uncovered from its oldest most forgotten recesses, just glimpsed in a kind of trance far beyond our daily experiences and the limits of our senses. Some have been quick to point out, “This is proof of the beginning of his madness”. Nonetheless, ended the professor, Nietzsche converted this intuition into a liberating thought with the power to transform us all into superhuman beings.

By the time it was Isabelle’s turn to speak, there was already much anticipation in the room. She began somewhat abruptly, raising her head rhythmically throughout her talk, and smiling indifferently at the end of each small pause: “Totalitarianism,” she began, “is the most successful figure of the solemnity of our faith in being… We could say that it is the exacerbation of the profoundly human tendency to compensate for the wants of being with an overdose of being. We don’t just see this in totalitarianism, however. The fullness of being is affirmed and reaffirmed in all official debates on politics, art, culture, religion, etc., also in our democratic societies. We need an idealized, idealist world, perhaps deified and adorned by a native happiness. And for this reason, those who have ironically insisted in the system’s discordant aspects have been expelled from the circle that is being closed with the same lively enthusiasm with which one attempts to exorcize the devil’s laughter. Nietzsche, lover of these avenues, inspired by these heights, suffered this exclusion, and is still being excluded to this day.”

She continued developing her argument, referring to an irrepressible fight between things and their meanings, between human beings and themselves, calling it the best definition of reality. “For this reason”, she concluded, “this fight is unleashed, and is always accompanied by the desire for lost, unrecoverable harmony, which is the desire that dominates in that construction of worlds in which the inessential takes on the appearance of the essential, and where a false harmony covers up a reality full of noise, dirt and cruelty. Only when it is transfigured in the beauty of an artistic illusion, wrapped in the dream of a myth and of Apollonian measure, can the absurd and terrible character of existence be contemplated, only then can it seduce one to live it.”

The auditorium, now more full of people than in previous talks, showed its satisfaction at the end of the conference with a resounding applause, and the other speakers made complimentary remarks and thought up various questions that Isabelle answered with brilliance and elegance.

“Take me away from here”, she whispered to me, approaching me when the next talk was about to begin. “I need a drink. It’s a matter of life and death”.

We went to a pub and she asked for a large gin and tonic with Citadelle. I complimented her on her success, although I noted that she wasn’t really enjoying it. She seemed indifferent, quickly changed the subject and began pondering the virtues of the botrytis cinerea, a bitter-tasting fungus used to sweeten Santernes wines. Then she added that what she really fancied for dinner were crépinettes scented with Piedmont truffle and ox carpaccio washed down with a good Burgundy or Moselle. And to end the evening tasting a good Krug Millésimé in an ice-cold glass while we gazed at the stars’ reflections on the surface of the lake. “Oh darling!, there’s no place like Paris to live life to the full, there’s no place like Paris to dream of a full life”.

The waiter returned and served her another round, this time pouring blue Bombay Sapphire in a wide glass full of crushed ice, while I stood there looking at her, intrigued by her mystery, an oracle of the occult that I attempted to decipher to sense what it was that she was hiding behind her face, behind her words.

“In love with Nietzsche, perhaps?”, I asked her.

“It’s difficult to be in love and be productive at the same time”, she answered. Her gaze returned towards an undetermined place, she became quiet and after a pause she added:

“To stand out professionally is difficult. The best thing to do to get attention is to say or do extravagant things.”

The only thing separating us was the glass with ice, which was slowly melting and sticking to the slice of lemon. With a sweet, serene gesture and a look from within, she continued: “The best lovers, if they really are in love, are in a rush to end their torment, and they do everything they can to liberate themselves from it. In order for the relationship to last, one should never swear to be in love. What love does not end up telling itself the little totalitarian story of its harmony, rebuilding a past in line with its aspirations, from which are excluded all doubts, all emptiness, all disappointments and infidelities? I think that, because of this, love — and not knowledge — is where human beings sign their most solemn pact with being. A pact which must be inseparable from parody, because there are no loves in which there is no adaptation to being, in which the misunderstood is not the most important person (the illusion of a full alignment with the other, right there with incommunication, tension and discordance), in which the only existing link is not that of jealousy of compassion, and in which the very idea of love is not continually betrayed by its figures. What I like about Nietzsche’s criticism is that it is still as hurtful and intolerable for many because it unmasks the mystifiers who manipulate and decorate this “reality” with fictions and absolute and totalitarian masks. These impostors don’t care about the truth that all authentic faiths always go hand in hand with doubt, and that the important things in life, like love, are never protected from the erosion of expiration, mistreated because of what we do to them.”

On Saturday, at the end of the congress, we spent a day out to Surlej. The birds flew across the sky at the start of the day while we began our trek up the mountainside. The daylight had a delicate, imperious quality to it, while the lake reflected in its stillness the blue of the sky, a few gray butts that crossed it and the vegetation of its shores. The beauty of the place gave the morning a sort of false euphoria that imposed itself on my imagination, as I remembered the words and conversations with Isabelle. “What beauty!”, she exclaimed, placing the back of her hand on her eyes to cover herself from the sun. Suddenly the sky began to darken and the day started turning into a strange night, bathed in a livid light that seemed to grow from the surface of the lake. An inverted light that was being projected back onto the black butts.

“What inexplicable means is this, do you think”, she said to me, “that converts white into black, the interesting into boring, the risible into essential or the fascinating into fearful? It escapes us. Meaning occupies, and encroaches on, the space of the absurd, the anxious confirmation of nothingness is soon alleviated by the firm weight of what is. This is our most common experience. But then, doubt and skepticism must always remain like the hidden face of our faith and of our original assent to meaning. Nothingness is not the absence of being, but its double interior, its inseparable opposite.”

Once we arrived at the top, the air mixed the fresh outpours of rain with the smells of the woods and the breath of the grass, its humidity quickly evaporating under the sun. From that height, the torsos of the mountains, as if rising up from nothingness, formed delicate, fantastic, imaginary scenes. Small pockets of vegetation floated on the blue mirror of a lake, slightly pushed by the wind, while the trajectory of my butts, reflected on the surface, created the illusion of a world which seems to be endlessly sliding by, but which, in reality, always stays the same, motionless.