Many is the novel that seeks not so much to tell a story as to make a point (Atlas Shrugged for instance). David Brooks’s 2011 book, The Social Animal, tells the story of a fictional couple, in order to make a lot of points. It is a sociology treatise in novelized form. Regularly, he interrupts the story to bring in the scientific research being illustrated. The characters are merely stalking horses for the science.

Many is the novel that seeks not so much to tell a story as to make a point (Atlas Shrugged for instance). David Brooks’s 2011 book, The Social Animal, tells the story of a fictional couple, in order to make a lot of points. It is a sociology treatise in novelized form. Regularly, he interrupts the story to bring in the scientific research being illustrated. The characters are merely stalking horses for the science.

Salvador Dali, “The Persistence of Memory”

This is a surrealist story, one might say an Eckhardt Tolle sort of story, because it unfolds in a perpetual now. Even though the characters age – the book follows their entire lives – indeed, we even meet the parents of one, before his birth – everything is set in an eternal 2011. That’s because Brooks is not seeking to discuss the past or the future, but to elucidate today’s life.

Well, for people like Harold and Erica. And they are not Everyman (and Everywoman). Oh no, this is a pair of overachievers of the chardonnay and brie set. Erica becomes a cabinet member, for Chrissake. Such people may not, technically speaking, be insufferable, but I do find it insufferable how they overpopulate literature. I guess it’s natural that writers like to write about people like themselves, and they tend to be more like Tom Wolfe than Stanley Kowalski.

OK, I admit to envy. It’s absurd and irrational (especially vis-à-vis fictional people); I have a great life, and if I lived Harold’s life I’d probably be wretched (as he is, for some of it). But still, he’s so successful, has so many interesting friends, and a social adeptness I never had. I’d really rather read about normal people.

At least Erica didn’t have the upscale life handed to her on a platter. She was born into challenging circumstances, overcoming which takes great force of character, which in the real world few can muster. But this, to his credit, is precisely Brooks’s point. Erica’s breakthrough was getting into a charter school at 13, via an extreme deployment of sheer will. The scene brought tears to my eyes – of exhilaration for Erica, and sorrow for all the poor schnooks left behind.

This is no mere fantasy. There are such schools, enjoying great success. But alas they are rare, and our hidebound, union-bound, bureaucratized public schools are incapable of emulating them. Thus we throw a quarter of our population in a garbage dump.

This is what fills the book: science-based information on what really makes people tick, often counter to conventional wisdom. Some is just plain fascinating. Like that women living together tend to synchronize menstrual cycles. And people named Lawrence disproportionately become lawyers. (I encountered a herd of Lawrences in my own legal career.)

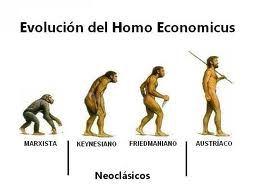

I have addressed the role of reason in human life, and Brooks’s book is very much about this. Certainly he is a man of reason, yet his position is not exactly mine. He attacks “scientism,” the supposed view that rational formulas explain everything, and the “homo economicus”

Actually, he makes a point of distinguishing between the French and British Enlightenments. He describes the former as seeing society and its institutions as machines to be dissected and re-engineered, while the latter sees them as infinitely complex organisms that dissection cannot fully understand. Brooks plants himself firmly in the Brit camp. But again I find his take too categorical. A fully rounded understanding requires not one perspective to the exclusion of the other, but integration of both.

Brooks seems to be neither a Democrat nor Republican, but a Sociologist. He sees one party wedded to government, the other to the market, but with both dysfunctionally oblivious to how much people and their behavior are shaped neither by governmental approaches nor market forces but, rather, by social forces – which he worries are fraying. With people less anchored into a rich fabric of social bonds and norms, one’s political faction comes to loom larger in shaping personal identity. This has transformed both parties into cults*, with politics becoming a war pitting identity group against identity group, heightening for each group the sense of “otherness” about the other. These are no longer disagreements among friends but morality dramas.** Trust in each other, and in common institutions, has collapsed, and compromises become impossible.

*The night before reading this chapter, I’d attended a concert by an assertively left-wing folk singer, so I knew exactly what Brooks meant in using the word “cult.”

** The other day I heard Alan Chartock, head of the local public radio station, on the air calling the Republican U.S. Senate leader “evil.” And in the next breath he decried excessive partisanship!